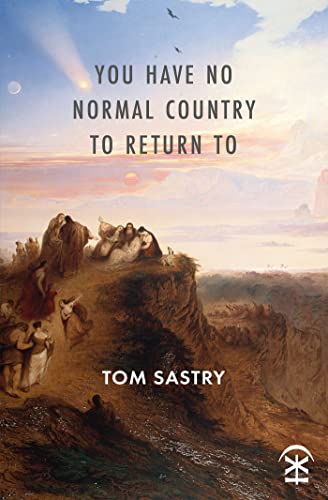

REVIEW: TOM SASTRY’S ‘YOU HAVE NO NORMAL COUNTRY TO RETURN TO’

Reviewed by Stella Backhouse

As a regular poetry critic, something I’m well-placed to reveal to you is that identity is the pre-eminent preoccupation of modern times. Tackling both his personal identity as a dual-heritage British/Indian man and the national identity of England, the country that is his home, Tom Sastry’s new collection You have no normal country to return to can certainly be filed under the ‘identity’ heading. But Sastry’s interest in situating his poetry within the context of politics, philosophy and history brings a refreshingly nuanced and questioning approach to what can often be a visceral and entrenched debate.

The collection’s most overt intellectual influence is the American political scientist Francis Fukuyama who thirty years ago, in a book of the same name, declared ‘the End of History’. What he meant was that with (what then seemed to be) the end of the Cold War, the world had achieved “the end-point of mankind’s ideological evolution and the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government”. The unfolding of the twenty-first century so far suggests that this has not gone entirely to plan – in turn prompting questions about why this is so. If there is no future, are we condemned to increasingly microscopic analysis of the past? How do we plan for environmental catastrophe if political evolution is at an end? Will we engineer crises just to relieve the boredom? Is the only alternative the atomisation of society into whatever narratives fit individual personal agendas?

But alongside its intellectual framework, You have no normal country to return to also asks emotional questions. Although contextualised by British colonial history, its primary focus is the tumultuous period roughly spanning the London Tube bombings of 2005 to the present day. It includes a handful of lockdown poems in a brief ‘Interlude’ between two of the headline sections, but its most powerful spotlight shines on Brexit, and specifically, on English Brexit. The tension in Sastry’s poetry seems to spring from the clash between personal empathy with and pride in the idea of isolation, and intellectual abhorrence of the referendum result.

The first proper poem sets the scene here, exploring the paradox of Queen Victoria becoming Empress of India during her long seclusion after the death of Prince Albert; but throughout the collection, Sastry brings together awkward, personally important but not-totally-logical ideas about not belonging/not being allowed to belong/but not wanting to belong/and taking an angry pride in not belonging. In his poems he creates gnomically surreal situations, told from the point of view of a maybe socially-inept narrator. He uses them to convey inchoate emotions or atmospheres that could pertain to either an individual or, by extension, to a nation.

Often these situations involve visits to the moon or contemplations of space, where space is either a place of possibility from which England has turned away – “Outside/there were no stars, or they weren’t as good” – or the ultimate in self-defeating isolation: “I didn’t know what to get the old man/so I took him to the moon. He…looked out and said/there’s nothing there”. The line “the earth rose without us/the loneliness was perfect” reminded me of the sun never setting on the Glorious British Empire, and of a teacher at school, who said she loved the saying ‘cut your nose off to spite your face’ because it was ‘so English’.

I ain’t gonna lie: because of its somewhat cryptic nature, I didn’t find this the easiest collection to review. But having said that, You have no normal country to return to is a brilliant example of something that poetry arguably does better than any other art form: it opens up spaces where difficult, counter-intuitive states of mind (like using the word yes as a negative) can be recognised and explored. For me, it is primarily a collection about the paradoxical lure of alienation and isolation, both self-imposed and imposed by others. Sastry does not analyse Brexit through the lens of class; his interpretation is more about tracing the self-assigned superiority of those who stand alone, based on a particular episode of the national story and editing out competing narratives: “The first line of defence is 1940. Volunteers patrol the beaches so unauthorised memories cannot land”.

This collection by Tom Sastry is available online direct from the publisher Nine Arches Press, as well as other bookshops and online retailers. We advise you to also check out his other Nine Arches Press collection: A Man’s House Catches Fire.