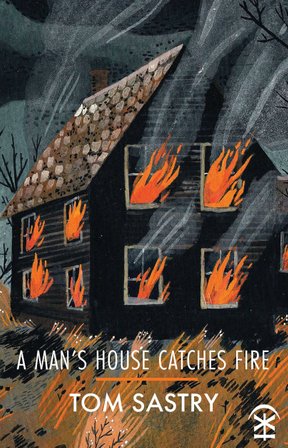

REVIEW: TOM SASTRY’S ‘A MAN’S HOUSE CATCHES FIRE’

Reviewed by Stella Backhouse

While I was preparing to review Tom Sastry’s clever, oblique 2019 collection A Man’s House Catches Fire, I chanced on an article about ‘lockdown-induced brain fog’, a phenomenon psychologists have related to Freud’s Theory of Drives. Briefly stated, Freud hypothesised “that we have one force inside us that propels us towards life [and] another that pulls us towards death”. The life drive, explained psychoanalyst Josh Cohen, “impels us to create, make connections with others, seek the expansion of life. The death drive by contrast, urges a kind of contraction. It’s a move away from life and into a kind of stasis or entropy”.

While I was preparing to review Tom Sastry’s clever, oblique 2019 collection A Man’s House Catches Fire, I chanced on an article about ‘lockdown-induced brain fog’, a phenomenon psychologists have related to Freud’s Theory of Drives. Briefly stated, Freud hypothesised “that we have one force inside us that propels us towards life [and] another that pulls us towards death”. The life drive, explained psychoanalyst Josh Cohen, “impels us to create, make connections with others, seek the expansion of life. The death drive by contrast, urges a kind of contraction. It’s a move away from life and into a kind of stasis or entropy”.

It’s not difficult to see a fit between these ideas and A Man’s House Catches Fire. In conversation with Nine Arches Press, Sastry said of the book’s three sections that much of the first one grew out of “being alienated from day-to-day life, unable to find any familiarity in everyday things”, while the third is based around “looking past the world’s imperfections to find things worthy of loving.”

Thanks to the pandemic, many of us are now wearyingly familiar with what Cohen calls “a contraction of life, and an almost parallel contraction of mental capacity”; yet at the same time, as Sastry captures in the poem ‘Thirty-two lines on loss’, the cautious inching back to ‘normality’ fills us with uncertainty. When the narrator mislays his glasses, he finds that idling his life away in a fog has its upsides: unable to engage with the superficialities of commercialism, he has space to think. The prospect of “functioning again” leaves him paralysed with dread: “My body was a sandbag./I cried like a doll”. And this is just one small aspect of the crisis; the larger issue is how humanity copes with the reality of living alongside an emergency that is never-ending, multi-faceted and beyond any individual’s control.

In ‘The unheroic’ for example, the narrator can only get his head round it (or perhaps distract himself from it) by comparing it to cricket: “government chaos, run on the pound/benefit sanctions, deportations./Of course it’s bad: one hundred and thirty for six/at lunch”. Elsewhere, it admits to nodding terms with timeless questions of how to go on living in the face of certain death, and with specifically modern disquiets like climate change and neo-nationalism. But the specifics are not really what matter here. What matters is its impact on the psyche.

That’s why the real meat of this collection is its meditation on the evasions, accommodations and compromises we all negotiate in order to be people who “wanted things to be different/but also/to love them as they were”. Success in this endeavour is not necessarily indicative of strength: the process may involve ‘unheroic’ surrender to group-think, denial, resignation, excuses and ‘normalising’ things we know are unacceptable. In ‘Complicity’, the country’s clowns have disappeared, for reasons unexplained. “No one feels guilty./There’s just this nostalgia.” So why mention guilt at all, if no one feels it?

Dividing the collection into three parts conveys evolving perspectives – but Sastry is also effective in retaining a sense of connectedness. All three sections open with a poem about a burning house. In Section One the house catches fire but ‘A Man’ remains inside; in Section Two he ‘learns to live with fire’, and by the time we reach Section Three, it is “no longer fire, just the knowledge of it”. (The obvious metaphor here is of global heating or catastrophe in general; but taken together, they also make curiously convincing menopause poems.) The collection as a whole is pervaded by an intangible but unsettling lostness – a watching of other people for cues while trying to suppress the suspicion that they’re just as lost as you are.

Imagery also carries over. Late in Section Two ‘The unheroic’ introduces the idea of taking life one breath at a time, which along with light and awakening, coalesces, in Section Three, into a flimsy but coherent strategy for nurturing hope. The halting, hesitant rhythm of ‘Home’ speaks of someone unused to having permission to relax: “I feel this life this home is not wrong/I have noticed that hope rising through the mix of things”. But when the final poem confirms that lurking fear that ‘Catastrophe lives at the end of the street’ – the question is: how long will it last?

Tom’s collection A Man’s House Catches on Fire is available to buy, either directly from the publisher’s website or from other bookshops and online retailers.

You can also read the rest of his Nine Arches Press interview over on their website.