INTERVIEW: FIRE & DUST MEETS ROSALIN BLUE

“And wild as creatures of the dark we love

like hunting through the forest of Eden

rising in the mists of fragrance

releasing our desire to the moon”

-Excerpt from ‘Hunters Moon’ [unpublished]

Photography credit: Tracy Morris

Rosalin Blue is a bilingual poet from Münster (Germany), who has been on stage since 1995. Since 2000, she lives in Ireland and has performed at many events in Cork and county, as well as festivals across the country, including Electric Picnic and LINGO. Her poetic home is poetry open mic event Ó Bhéal (in Cork city centre), and her poetry has been anthologised in On the Banks, A Journey Called Home, and Cork Words 2, and published in magazines including Southword, Revival, Crannóg, A New Ulster and Solstice Sounds II. In 2023, one of her poems was shortlisted for the Fish Poetry Prize. Since 2020, she has been facilitating the Blue Mondays Writing Group and has edited/published their 2021 poetry anthology. Rosalin’s books include a poetry collection In the Consciousness of Earth (Lapwing, 2012) and a translation of August Stramm’s YOU. Lovepoems & Posthumous Love Poems (Monsenstein und Vannerdat, 2015). Her first album of poetry to music Like Day & Like Night was launched in 2023. Currently, Rosalin is studying for a Diploma in Translation.

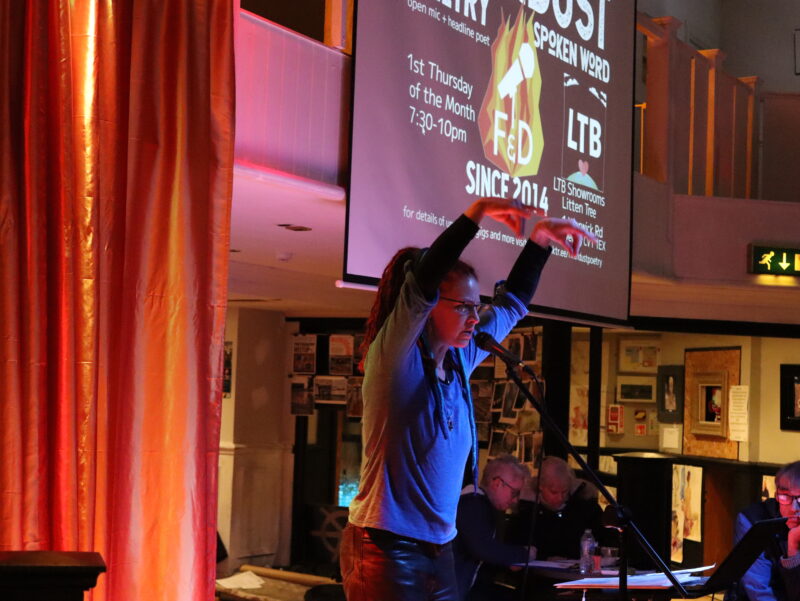

In 2023, Rosalin was one of two poets representing Cork city in the annual international Cork-Coventry poetry exchange. You can find out more about the exchange here. Audiences enjoyed her words at both the welcome event in Kenilworth’s Tree House Bookshop on 1st November and our Fire&Dust Twin Cities special at The LTB in Coventry city centre on 2nd November.

HCE caught up with Rosalin after her visit, to ask a few questions…

HCE: Tell us a little about your background and journey as a writer so far. What inspired you to start creating poetry, and how did you initially find your way to poetry open mics?

RB: I’ve always wanted to express myself in writing, so I taught myself how to write before school. My first ‘writing flash’ happened in nature, cycling somewhere in Germany with my older sister, blue skies over the valley, all sounds of the village below clearly rising to where we were, and a buzzard’s cry above. I had only a piece of tissue-paper to write on. When I read the outcome out loud later, my sister asked who I was quoting. I said it was my own, and she responded: “You have to continue that!” From then on, I was hooked. I was twelve.

Growing up with two sisters and a brother in a loud and loving teachers’ household, our parents always supported our endeavours and recognised the linguist in me early on. Aged sixteen, I shared my poems with my first real love, who equally encouraged me, saying: “You have to publish that!”

Just three months afterwards, in 1990-91, I went to the U.S. for an exchange year, going to high school at senior level and living in a family. This is where my English became fluent and I expressed myself a lot in writing. We had a fantastic teacher in Humanities and British Literature, Mrs. Jones, who taught super-inspiring lessons. That’s how my first poetry in English was born. We read Old- and Middle-English, which rooted me into the language. I also took French and Spanish, which seeped into some of my poems as well. My writing continued mainly in English until I returned to Germany to finish school.

In 1993, I went to study what was then called “Kulturpädagogik”. It’s about how to get the arts to people, from the level of workshops all the way up to culture-politics. Basically, Arts Administration with two artistic majors, in my case Literature (plus Theatre and Media) and Visual Arts (drawing, painting, sculpting), and two application subjects, for which I chose Psychology and Education. An inspiring course, which ultimately gave me an MA in Applied Culture Studies from the University of Hildesheim. During this time, I continued writing poetry and joined a writers’ circle in the town, run by the LiteraturBüro Hildesheim. The director, Jo Köhler, organised poetry events in various locations and invited us to read along. My big opener on stage was in 1995 as part of the writers’ circle’s first anniversary event, which I also co-emceed with my poetry-partner Frank. I always went the full way in performance, including whispers, screams, movement, or the sound-effects of ripping fabric, sometimes even action-painting with a poem. After that, Jo involved me in many more events as poet and MC, and later took me on as an intern.

Frank and I went on to facilitate the writers’ circle for a year, before we founded our own group, the Poetry Initiative KONTEXT in 1998. Until 2000, we organised three events in Hildesheim, involving different art-forms and groups with a range of poetic voices to perform. Meanwhile, I also dipped into the poetry world of Hannover and Düsseldorf, where I got booed off stage at my first poetry slams. German audiences are a bit rougher, and if they don’t like a poem, they will vocalise this at a slam. I was better suited for calmer events, often as part of a set of five or six acts in different settings.

In 2000, I came to Cork for work-experience with the Munster Literature Centre for eight months, which was run by poet Patrick Galvin and his wife Mary Johnson at the time. They introduced me to many now big names in the Irish poetry world, from Gregory O’Donohue and John Montague to Gerry Murphy or Matthew Geden. They also published some of my poems in the print edition of Southword Magazine.

In that same year, I met my partner, and, after finishing my studies in Germany and having our daughter, we moved back to Cork in 2005.

I picked up the thread in 2008, after finishing my thesis (comparing my own poetry with that of Expressionist August Stramm among others), and started going to Ó Bhéal. Back then, the event ran every Monday, and it has since become my poetic home. It’s like a family, with many friendships grown over years. You really get to know people through their poetry and see them evolve, which is a pleasure. Compared to Germany, open mics are a big thing in Ireland. It’s where poets cut their teeth, so it’s amazing to have such an inclusive and respectful community. Yes, it was in Ireland, that I got into open mics.

I never went back into event organising until founding the Blue Mondays Writing Group in 2019. Ó Bhéal was going from weekly to monthly, and the community was looking for other poetry events to keep in touch. Building on the knowledge of everyone involved, our group is a space to work on poems and get feedback from each other. Just a few months after we started in-person, the lockdowns brought us to Zoom. During that time, in 2021, we published our Blue Mondays Poetry Anthology. When lockdowns finished, Cork City and County Council involved the group in a few outdoor events in Cork and Bandon. Nowadays, we meet on Zoom once a month to critique the words in detail, and a fortnight later we meet in-person to get feedback on performance. I look forward to what the group may bring next.

Photography credit: Tracy Morris

HCE: Would you say there are themes or motifs that you tend to gravitate to in your work?

RB: Absolutely. I’m currently gathering my second poetry collection, and the list of themes always turns out roughly the same: Home, poetry, relationships, nature and animals, psychology and the spiritual. I also have some political stuff, and plenty of sexy poetry, including poems about the female cycle, motherhood, and menopause.

Since my brain injury ten years ago, the experience of recovering with all its pitfalls and successes makes an appearance as well. The injury totally disrupted my path, I was on a good trajectory in 2013 before my crash, and I’m really only just back on track now. Life has humbled me a bit. However, this has made me a more empathetic person, I believe.

My writing practice was massively affected by the injury. Where I used to have lots of writing-flashes before, I now have to bring on the “poetic mode”. I kind of build a poem now, gathering what I want in it, finding its rhythm and voice, until it eventually begins to flow with the same kind of inspiration. Translating poetry can also bring on this poetic mode.

HCE: Was Like Day & Like Night your first time working with musician Rik Appleby? Can you offer our readers some insights into the collaborative process for creating a sonic poetry album?

RB: The idea for making an album of spoken poetry to music began in my teens, inspired by the English-Irish poet Anne Clark. Rik Appleby, I met first in 2000, but it wasn’t until 2017ish that I reached out to him with the suggestion of making a poetry album. It took two more years before he got back to me (that was during lockdowns), and then another year before we eventually started working together. I travelled up to his place in West Cork for a whole weekend once a month, and we interrupted work only for food and sleep. It was all very relaxed, inspiring and great fun!

The creative process evolved organically. I chose a few of my poems to work with and he asked me what I envisaged for their style. I introduced my musical inspirations to him or likened the pieces to a band or project. You can tell Rik “Create me an atmosphere of flying, or an underwater landscape”, and he will. On the weekends, we’d pick one piece or another, I’d perform it a few times while he’d feel out the beats and rhythms or its character, and then he’d lay the rhythm down, or a bass track. One piece even began with a live-take of him accompanying me on guitar. Other poems popped up in conversation, and we tried things out during a session.

We layered the different instruments and sounds and later co-opted musicians to add flute, saxophone, piano/organ, drums, percussion, and vocals. All topped up with soundbites enhancing the poems. When we had ten pieces, Rik suggested to wrap it into an album. We still have more ideas to develop in the future…

Photography credit: Tracy Morris

HCE: The album ‘blurb’ encourages people to dance as well as listen to it. Do you think audiences engage with poetry in a different way when it is accompanied by music? Similarly, in what way does the involvement of music affect your writing practice?

RB: For me, music has the power to carry a message, sometimes stronger and farther than poetry. So, we stretched the pieces with music in places to take a message into dance and ponder on it. You can take a line into life that way in the rhythm of your body.

When we created the album, I experienced the music around us in the room. I love dancing, myself, so I think as a dancer when I feel and make music. We ultimately arranged the tracks on the album by their speed, forming a mini 5-Rhythm-wave for the dancers, from slow to top-speed back to slow.

As far as audiences go, people know to be quiet and listen to poetry, while they often talk during a concert, which is a distraction in the live situation. So far, people have taken the album as sonic poetry and sat, or even danced, quietly. But I’m happy to report that I have seen the music cause the goosebumps we wanted to achieve. I believe most of the dancing will happen in the home-room listening to Like Day & Like Night.

All poems on the album were straight poems from their beginning, so they weren’t written for music, neither did we adapt them for the album except for the stretches. Some, like ‘The Torn & The Dancing’ or ‘Down in the Sunless Sea’, were conceived with the idea of musical accompaniment within them. Others, like ‘Drinkers’ or ‘Summertime Laze’, have an intrinsic musical style, often in the rhythm of the poem. However, the structure of the tracks is like in poetry, especially ‘At This Evening Hour’, with its frame in the soundbites. It was fun contrasting a musical genre like Gothic Rock with a spiritual message (‘We Are Receivers’) or embedding an uncomfortable truth (‘The Unwanted Children’) in a strong tradition of love with Reggae.

What’s really affected by the music is performing. Because with music, I find myself constantly counting between lines in order to get my cues right. Pauses in poetry performance are more intuitive in length, whereas with music, you’ve got to stay with the beats. My background in choir is helpful, so this is not entirely new to me. The live situation always creates little variations on a night anyway. But yes, counting is the biggest difference for me.

I haven’t written for music as such. Only a few poems have become songs or offer themselves to musical realisation. However, those have nothing to do with this album. I have a different project loosely going on with a friend of mine. We’ve been writing lyrics together and developed a few songs from them. The process is completely new to me and very unlike writing poetry, more like building with Lego. But that’s a completely different project to the sonic poetry idea I’ve developed with Rik in Like Day & Like Night, where the thing is to speak the words to the music.

HCE: In your opinion, is Cork a good place to be a poet/creative? How does it compare to your time living in Münster – is there a thriving poetry scene there?

RB: I fell in love with Cork during my work-experience in 2000. Not only was I working with the Munster Literature Centre, in my leisure time I also attended lunchtime readings at Tígh Fílí, which is where I had my first poetry performances in Ireland. But in the rest of the time, I went busking with my djembe-drum – first a big one, then a second smaller one – and connected into the street market back then. It was a very protective creative environment, with street performers, vendors, buskers, and beggars all looking out for each other. There were many drummers in town that year and we had some of the best sessions together. I also went travelling with both drums, and learned how to play entertaining rhythms on my own. Haven’t done that for years now. That year, I made many friends who have become influential in Cork’s cultural life in various ways. Cork just is that kind of place: It’s easy to get to know people and connect with other creatives, meet the organisers, and get involved. Once they realise you bring something to the community, you’re in with a chance. It’s a nurturing environment that has allowed me to come out of my shell and encourages me to be who I am and live out my talents.

That’s where Germany is different, they have much higher expectations, which makes it harder to thrive in the creative environment. Further, poetry is respected much higher in Ireland, being an oral culture, than in Germany. Doing poetry performance wasn’t a big thing when I started out in 1995, so it took a lot of courage. There are many poetry events today, but audiences are often older and smaller, the reading is done by trained actors instead of the poets themselves, and poetry of the past is more celebrated than that of the present.

That said, during my University years in Hildesheim I was involved in a revival movement to breathe new life into the poetry world. One exam-paper for my Masters was on the literature sector in Germany, which is organised by each of the sixteen federal states. Back then, literature organisations were beginning to receive regular funding. Now, there’s a whole new structure. Each state has regional and state-level slams leading to a national poetry slam. Then there’s all the “page” poetry events going on, so the sector has developed massively since I left Germany.

In Münster, there is a huge scene, including a regular poetry festival, a poetry-film festival, and slams where the audience is the judge. I haven’t been able to visit often enough to really know the environment. When I did visit for a slam, English and political poetry were not so welcome, and I felt it was less open than Cork, but that might just have been the German mentality. During my school years I never grew into the scene in Münster, because my poetry life wasn’t public before I left for studies. If I lived there now, I’d have to prove myself first before being accepted. This would include adapting my current poetic style back to the popular poetics of German poetry, never mind reconnecting with the language…

HCE: You came to Coventry in November as part of the Cork-Coventry exchange. How was the experience for you?

RB: I felt hugely honoured to have been chosen as part of the Twin-Poetry exchange for 2023, and I really enjoyed the trip. Getting to know Coventry and Kenilworth with their landmarks and sights was very interesting and I learned a lot. Most of all, I enjoyed spending time with Cathal Holden, who was my poetry travel partner, and hanging out with John Watson and Devjani Bodepudi again after their visit to Cork earlier that year. Getting to know Ann Atkins and all the folks involved in the poetry scene around Fire&Dust and PGR was a great honour. In both places, the audience reception was warm and friendly, we each got fantastic applause, and I sold a bunch of books and albums. I only wish I hadn’t had such a bad cold during the trip, because people were eager to speak to us after the events. I would have loved to hang around and chat more because I’m a real night-owl, but my health forced me to draw back to the Premier Inn. In the same way, I could have been more chatty and curious on our visit to the Council House to meet the Lord Mayor, during the interview with Hillz FM Radio, and on our trip to the FarGo village. The weather didn’t help either. I guess that’s a good reason to come back and explore it all again in summer.

HCE: Compared to what you’ve observed in Ireland, did you notice any interesting differences between the poetry/gigs/attitudes in Cov and back home?

RB: The poetry scene seems very similar to the one in Cork, equally open and warm, a grown community. In relation to diversity – everything from age to gender, ability, and culture – it was as inclusive as I have experienced the scenes in Irish places. I loved the cute ‘Tree House Bookshop’ with its stuffed walls, and was wowed by the setting the LTB showrooms provided. Not only such inspiring visual art around the building, but also the stage done with that orange backdrop, and the light-elements in the room all enhanced the beauty of the event. The structure of the poetry night, with open mics embracing the guest poets, was an interesting new format for me. Other than that, it felt great to be among fellow poets who love to do poetry as much as I love it. And in that way, all poetry scenes are the same, really, aren’t they?

Photography credit: Andrea Mbarushimana

HCE: Your digital art exhibition ‘Like Day & Like Night. The Poetry Illustrations’ was hosted by Cork City Library across March 2024. Can you tell us a little about it? Did people connect with the experience of combining music and poetry from the album with visual images in the ways you hoped they would?

RB: It was an honour to exhibit the 12 illustrations I made for my album in the forum of Cork City Library. The launch was a very small affair, but those present enjoyed my performance surrounded by the images in the space. I was told by staff that many asked about the exhibition in my absence. I think the deeper connection for people will come when they listen to the album at home, maybe dancing and looking at the illustrations.

The term “digital collage” raises different expectations today. My images were simply created digitally at the computer, and were put together like a collage, illustrating each poem sometimes in a very humble way. I could imagine a very different exhibition, with the images projected onto the wall, maybe showing details, zooming in and out of different areas of the illustration etc., while the respective tracks are playing. That would result in true digital art. The possibilities are endless…

HCE: People don’t always appreciate the work that goes into translating a poem, to attempt to capture not only the language and meaning but also the essence and rhythm, etc. Do you consider translation an artform in its own right?

RB: Absolutely, yes! I believe you need to be a poet to do good poetry translations. Poems are like riddles, and translating them feels like solving the riddle. You need to understand them deeply to be able to translate them. The term ‘transcreation’ describes the process better, because from the first raw translation, you re-create the poem in your target language. Transferring metaphors and figures of speech can sometimes be tricky, but they’re a normal part of a translator’s job. Capturing the meaning can be a bigger challenge when it comes to idioms, puns and ambiguities, and often you have to drop one or the other nuance. However, you will also create new relations between words and lines, that can reveal completely different layers of meaning in a poem.

And then you need to respect the various poetics of the different cultures with their aesthetics and measures for quality in the translation process, which adds another layer of difficulty. For example, German poetry works with wordplay of ambiguities that create double-meanings between different lines in a poem, which often get lost in translation. We also deal differently with repetition than contemporary Irish trends.

I believe it’s important to re-create a poem’s form as closely as possible to the original, and if it has meter and rhyme, I try to replicate that. This is the biggest challenge. It begins with noting down a rhythm-and rhyme-analysis of the original, so that the new translation falls into that form. Most tricky is the rhyme scheme, for which you need to re-arrange the lines grammatically, so the rhyming words are at the end. From there it’s a mere synonym search. I often resort to near rhymes, or even a different rhyme-scheme if necessary…

Photography credit: Tracy Morris

HCE: All the international writers I know who write in English say they love the language but have stumbled upon concepts, phrases or idioms from their mother tongues that are beyond translation, as they have no equivalent in English. Does German have many of these, and what are your favourites?

RB: Cultural and lexical gaps exist between all languages. That is because languages define our world, and each language or culture offers a completely different perspective on life. Where a concept doesn’t exist, there is no word for it. In the same way, I often feel I’m a different person when I think in English or German respectively. What’s nice about German is, that it has a grammatical flexibility you can build trees with, which English does not have because it dropped the inflections of its words. That said, English has a very slender, snake- or eel-like quality and can get to the point quite swiftly. In that way, all languages have their individual beauty. German is such a descriptive language, the words are constructed like Lego. Yet, it’s not far removed from English, so you can always find a superordinate word to create a translation when there is no direct one available. Only in the case of neologisms you need to be inventive and work with translating the individual morphemes in a word. To me, that’s the top challenge in poetry translation.

My favourite untranslatable idiom, word or concept? I think for now I’ll go with how German can create long composite words, that can not only unite very diverse concepts, but also contain many possessive relations. In English you’d have to say “of” all the time. The famous endless “Donaudamfschifffahrtsgesellschaftskapitän” literally means “captain of the company of voyages of steamships on the Danube”.

HCE: What type of poetry do you seek out for personal enjoyment? As a reader/listener, when you engage with another poet’s work, what are you hoping to get out of it?

RB: My measure for good poetry is goosebumps, whether I’m a listener or a reader. Poems challenge me like riddles. When I feel I’ve deciphered them, they give me an experience. Some hit me straight in the heart, make me think, make me laugh or cry, but the best ones give me goosebumps when they move me. I need to read a poem over and over again before it opens its meanings to me.

I love going to open mics, because hearing poetry from the poet’s mouth creates the context for understanding a piece, which is often easier than reading it alone. Coming from a different language can make it harder to “get it” on the page, so voice and body-language make all the difference. I like group conversations about a poem, because all the perspectives help decipher it.

When I seek out poetry at home I like it abstract. My pet passion are the Expressionist poems from 1910-20’s Germany, specifically August Stramm (whose 150th birthday is on July 24th). I also enjoy the Dadaists, because they are funny in their experiments. Further, I’ve translated some of the classical German rhymed poems into English, such as von Eichendorff, Tucholsky, Rilke, Heine, or Annette von Droste-Hülshoff, most famous poetess from my hometown Münster. These translations can be found here. I’m also a Romanticist, I like Wordsworth, Coleridge, Yates… and contemporary Artists like Jim Morrison, Leonard Cohen, Anne Clark…

Most recently, I read Catherine Ronan’s first collection Elemental Skin (Revival Press 2023), which is very abstract and a real treat. Next on my desk is Gerry Murphy’s “Setting the Globe in Motion” (Moloko Print 2021) with his witty poems in English and German. There are so many poets and poems I haven’t read yet, I need another life to get through my book list.

As for performers, I was honoured to come to Coventry with Cathal Holden, whom I hold in very high esteem as a poet and storyteller. At Ó Bhéal, I enjoy witnessing how people grow as poets. Mary O’Connell, sadly missed, was a superb performer. Phillip Spillane comes to mind, Leanne O’Sullivan, Molly Twomey, and I just love Jim Crickard’s poetry-performances. There are plenty of Cork people I like hearing, and on Zoom we have great poets from around the globe as well! A great bard in Dublin is John Cummins, and I heard the best stuff there in 2014 at the Lingo Spoken Word Festival. I believe there are plans to bring back a Spoken Word Festival in Ireland soon to gather the scene again!

HCE: Your work has featured in a good number of literary journals and anthologies. Please could you offer our readers your top piece of advice when it comes to submitting poetry to publications?

RB: Wow, that sounds big. Well, I’ve had many more rejections than accepted poems, and so far I haven’t won a prize yet. For what my advice is worth, it’s about presence, participation, patience, persistence, and regularity. Sending out submissions is its own admin job to stay on top of. It’s not easy to get into journals, to find the ones that like my stuff, but sometimes I’ve been lucky. It’s important that poems are well edited and proofread, and correspond with the journal’s interests. You just have to keep at it.

As for the anthologies, the credit goes to Cork City Library who have a brilliant outreach programme to include writers in their annual festivities. The Cork Anthologies or the Poetry in the Park project are only two examples of how Patricia Looney and her team involve the local community in events and publications every year. To catch these kind of opportunities, it is important to be an active participant in the poetry scene and keep in touch with the organisers.

Photography credit: Andrea Mbarushimana

HCE: What’s next on the horizon for you? Are you already working on the next project?

RB: Yes, I have a hungry mind, so there’s always something. At the moment, I’m focusing more on the translation studies for my Diploma and on my little business, than on poetry. In 2024, I set up self-employment with editing, interpreting and translation between German and English, and I teach German as a foreign language as well.

I’m currently putting my second poetry collection together, hoping for a bigger publisher this time. However, selecting and editing the poems is a process that takes its own time. I’ve also been trying to get gigs with my album, but I’m all new to organising music and it’s difficult to find interested venues. If I can get some help with that, I’m sure I’ll promote further performances soon…

HCE: What’s the best way for people to keep connected with you and your work, or contact you for bookings?

The easiest way to connect with me is via email, Facebook messenger, and WhatsApp or Mobile. Friends can see contact details on my FB profile. I am still resisting Instagram or TikTok to keep an overview over my social media…

YouTube Facebook HearNow Spotify Artist Profile

If you’re interested in my language services (German-English) on a professional level, please find me on LinkedIn:

LinkedIn

HCE: Is there anything we didn’t cover that you’d like to share with our readers?

RB: Yes. I often get asked about my name. Rosalin Blue is a pseudonym that was given to me in an anonymous literary mud-fight via post, way back in 1994 before I began publishing. The name was a reaction to my poetry and art that I exchanged with a fellow student. I immediately liked it for its sound and took it on for performances and publishing. Pronounced in German, it is very soft and contains all vowels and all types of consonants. I had no idea about any connection with Ireland until I came here. People in Cork then connected my real first name, Sue, with Blue for the rhyme of it. And that’s almost cooler than Rosalin Blue.

Rosalin’s sonic poetry album Like Day & Like Night can be listened to here.

More about Rosalin and Cathal’s exchange experiences, as well as those of Coventry poets Devjani and John, can be read here.

Here Comes Everyone is grateful to acknowledge the continued support of partner organisations who have funded and/or championed the exchange scheme, in 2023 and previous years: Coventry Association of International Friendship (CAIF), Coventry City Council, Coventry Peace Festival, Nine Arches Press, Writing West Midlands, Cork City Council, Ó Bhéal and DeBarra’s Spoken Word. Special thanks for their involvement also goes to Paul Casey, Moze Jacobs, Ann Atkins, John Watson, The Long Valley pub in Cork, DeBarra’s Folk Club in Clonakilty, the team at The Tree House Bookshop in Kenilworth and The LTB team in Coventry.