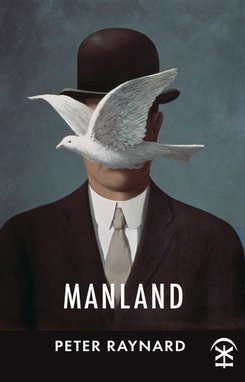

REVIEW: PETER RAYNARD’S ‘MANLAND’

Reviewed by Stella Backhouse

Sometimes – to paraphrase Tammy Wynette – it’s hard to be a man. In the last few years alone, the patriarchal throne has been rocked by #metoo’s exposure of the sickening ubiquity of inappropriate male sexual behaviour towards women. The huge differentiations between them notwithstanding, men en masse are now routinely critiqued as automatically privileged and therefore able to impose narratives that benefit them onto groups (most notably women) who benefit less. In a historically patriarchal society, these are major shifts in attitude. But for men to talk about them – without appearing as woman-hating incels, lobbing fistfuls of sour resentment from deep within the Mancave of Grievance – can be the hardest thing of all.

Peter Raynard deals with the touchy issue of feminist-blaming by ensuring women are largely absent from Manland, his recent collection on the theme of masculinity and its discontents. As the opening poem ‘Maelstrom’, with its strings of witty puns on ‘man’, ‘men’ and ‘male’ makes clear, this is a collection whose focus is the man-verse alone. Unlike Antony Owen, whose collection The Battle covers similar ground, Raynard does not appear alienated by conventional working-class maleness. He likes meeting his mates in the pub. He likes watching football. His questions are around how this traditional model of masculinity has – for better or worse – impacted men in the past and, as patterns of employment and family life change, how men are adapting to its declining relevance.

Shockingly, one way they are adapting is by not adapting: three-quarters of British suicides are men, and on average twelve men a day in Britain will take their own lives. It’s a heartbreaking statistic addressed by Manland in a number of poems, including ‘these boys’, where it’s approached through the long-view lens of later life that is an important ingredient in the tone of this collection. Raynard is sixty-ish; from this vantage point he is able look back over the lives of himself and his male friends and family, trying to make sense of how living within traditional masculinity has impacted them. In ‘these boys’ he remembers six very individual characters, at least some of whom he apparently knew since school, who were arguably failed by school, and went on to take their own lives.

But this is a collection about looking forwards as well as back. In ‘We’re the last now, for sure’, Raynard balances himself within a transitional generation, poised between their fathers’ industrial-jobs-for-life pub culture and children who “hold the wild reins now, sailing across a world/drenched in postmodern idolatry”. And while there is regret at the passing of a cultural narrative that defined the identity of generations of men, there is also awareness of its limitations – “praise the young men who sign off/with an x to other male friends…Not held back by the pantheon of past men” – along with concern for what comes next (“My dick is an absent father never done the dishes nor changed a nappy dick…My dick is an Aryan, Proud Boy, Oath Keeping dick…My dick is more sexist than your dick”).

Perhaps in homage to the forwards/backwards theme, Manland mixes modern forms with some quite lovely examples of traditional structures. It is ruefully humorous on those great male levellers, of hair loss and prostate problems; and it contains two sequences. The first of these threads through the collection documenting episodes in the life of Home-Father, who looks after house and children while his partner works outside the home. In an odd way, these poems, with their tales of battling other people’s pre-conceptions and feeling vulnerable in the opposite sex’s space, are the poems that come closest to being about women. The other sequence, ‘Swimming Away in Circles’ is an album of heartbreaking snapshots of lost people interviewed by Raynard for a project on drugs. The tender sonnet format used to describe them returns to them at least a little dignity and humanity.

In Manland Peter Raynard instigates a calm, empathetic conversation about a subject that, bristling behind minefields of anger and extremism, can find itself labelled ‘too difficult’. Crucially, it doesn’t blame men. Instead, it advocates examining how the imperatives of capitalism and patriarchy have conspired to create conditions that harm all genders.

Manland is available to purchase online, direct from publisher Nine Arches Press, as well as other bookshops and retailers.