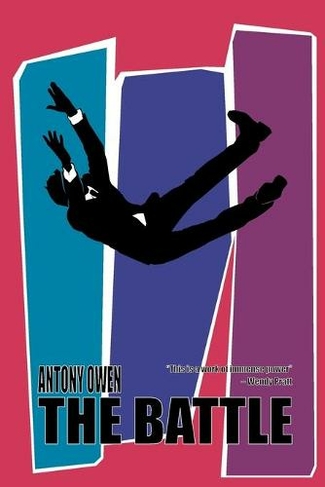

REVIEW: ANTONY OWEN’S ‘THE BATTLE’

Reviewed by Stella Backhouse

When a poet whose reputation rests largely on his powerful critiques of war and its shattering traumatic legacies produces a new pamphlet entitled The Battle, you’d be forgiven for assuming that he’s back mining the same rich seam – covering it from a new angle perhaps, or focusing on a lesser-known conflict. But in the case of Coventry’s Antony Owen, you’d be wrong. The sobering truth is that even after so much – and such profound – engagement with the subject of war, in Owen’s personal lexicon ‘The Battle’ refers not to bullets and bombs but to his own years-long fight to be diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD).

This is not a tale of simple cause and effect. Concentric walls of exclusion leave Owen feeling frustrated and disempowered. From childhood, he does not conform to the narrative of masculinity expected by the culture he grows up in. That culture’s inability to accommodate or describe him – beyond calling him “odd” – leads to two suicide attempts and as a side-effect of the drugs he is prescribed for depression, emotional numbing and sexual dysfunction. Disarmingly honest, The Battle bravely tackles these taboos of male experience, confessional-style; but the fact that this very honesty is what makes the collection stand out, is in itself a commentary on men’s inability to talk about their relationship with masculinity.

The Battle spans much of Owen’s life, from childhood, through adolescence – when he attempted suicide for the first time – into adulthood. Interestingly, given that the office environment is not traditionally viewed as fertile poetic ground, workplace culture (especially the testosterone-fuelled arena of sales) is where much of Owen’s earlier unease begins to crystallise. The supposedly sympathetic Human Resources department repeatedly emerges as a platitude, tacitly colluding in harmfully narrow narratives of masculinity. After a friend’s suicide Owen says “[my boss] sent me a gif to remind me I’m only human…[he] told me that it’s been three weeks/that it’s time to man up and hit target”.

This viciously-cycling disconnect between ‘man’ and ‘human’ is perhaps most poignantly exposed in Owen’s confession of sexual dysfunction secondary to anti-depressants. He says “I am having problems getting hard…You cannot make love if you’re depressed or half a man.” And again: “I have no feelings./The dark sides of the daily moons I swallow/are anti-depressant, anti-human.” The irony of treatment for being too human to be macho is that it leaves Owen feeling too unmanly to be human.

This is a complicated story. Although Owen wants to be told he has ASD, he recognises that labelling may be the reverse of liberating. In ‘Autism Hiding’ he compares himself to a jam-jarred fish or dissected butterfly, conveying the opposing impulses to be seen/not seen at the same time: “We are not to be trapped or pulled apart, and yet it is our fate./If you see such a thing, you will want to capture it at least once or kill it over.” He characterises ASD as something ducking in and out of sight “taking the light, becoming dark for it./Leave your jam-jars and nets and I may let you see me.” This nuanced understanding itself contrasts with the parroting of clichéd words like ‘special’ and ‘unique’, which are meaningless unless accompanied by action.

But even this is not the whole picture. Owen’s anxieties are further compounded by an apparent belief that he has betrayed a self-imposed ideal of childhood purity. Of his teenage suicide attempt he says “I remember my little brother’s eyes rash-red from weeping…he grew up that day – and that was my murder.” Of his adult attempt he says “Should I cover my head in shame with a towel/not to offend God for innocence so morbidly devoured?”. He fantasises about stopping time. The literary figure with whom he identifies most is Holden Caulfield.

Like a blurry Venn diagram with the components ‘man’, ‘human’, ‘pure’ and ‘soiled’, The Battle is is both a personal exploration of the shifting boundaries between imprisonment and exclusion and an important articulation of the restrictiveness of macho culture and its crushing impacts on individual men. Owen’s cry is for freedom: why not “look up to the rooftops until you see only clouds./Elect the utopia of sky”.

The Battle is available online direct from publisher Knives Forks and Spoons Press, as well as other bookshops and retailers. Two of Antony’s other books – Cov Kids and The Unknown Civilian are also for sale on the KFS Press website.