Is Your Poem Overwritten or Underwritten?

By Tina Sederholm

My first writing teacher, Roland Fishman, used to say, There’s no feeling like having written. Going from a blank page to having a first draft of a poem fifteen minutes later, often something you had no idea you were going to say; he’s right, it feels pretty good. But then what?

Occasionally, a poem will arrive fully formed. But that’s the exception. There’s rarely a first draft that can’t be improved with some judicious re-writing and editing, so its true brilliance can shine out.

Always start by putting your first draft away for 24 hours, or better still, several days. You need to get some distance from it, so you can come back and look at it dispassionately. When you take the poem out to read again, listen out for your gut responses. Enjoy the poem, but notice when your gut or heart tightens, or the moments your mind goes fuzzy. Are there parts you had to read twice? Something that feels off? And what about the parts you skim over?

These are all little red flags that the poem is a bit rough. When I re-read my first drafts, I have a pen in my hand to mark a dot or cross by those parts that make me react. I don’t stop to think why, I just note it.

Then I read the poem again, out loud. This helps me notice if the rhythm is off, or if there are so many words it feels like I have a mouthful of marbles. Again, I dot the places that aren’t working.

The third time I read it, I go slow. Pause by each dot to figure out why I put it there. If it’s not immediately apparent why something isn’t working I ask myself,

Is it overwritten or underwritten?

You can spot if a poem is overwritten if you get that mouthful of marbles sensation, lose the rhythm, feel weary, or your mind wanders at any point. Our brains tend to work in a circular way, we repeat thoughts over and over. So it’s not surprising in poems if we have several goes at an idea, or return to the same point, three stanzas later.

The good news about overwriting is that you’ve got lots of material to work with, and on the whole, it is easier to take away the excess to find the beauty beneath, than to add new material in. The bad news is, you as the writer may find it hard to let go of your darlings.

However, you must try. If you identify overwriting in one of your poems, pick out the best ‘go’ at the idea, the sentence which feels like the arrow that hits the bullseye, and delete the rest. Anything wide of the mark needs to go. It clutters the page, and more importantly your listener’s ear. The audience can’t hear your great lines, if they are surrounded by mediocre ones.

An underwritten poem usually starts well, but then rushes, often with incomprehensible leaps, before ending abruptly with a trite or unsatisfactory ending. Underwritten poems often have many clichés, rhymes for the sake of convenience or use general language; The Tories are evil, climate change is wrong, that sort of thing.

In the case of underwritten poems, you need to take a deep breath and dive deeper into your subject matter. Often there is something you are scared to say, or haven’t completely articulated. Ask yourself,

How could I be more specific?

Another good entry point for underwritten poems is to free write in response to the question,

What I really want to say is…

Or to free write about the subject from another perspective, perhaps a person who has different beliefs to you. This will give you more source material, or provide the twist that might be missing from the ending.

Of course, a poem can be overwritten in one stanza and underwritten in the next. Discerning which applies to your poem means you now know whether to re-write all or some of it, or if you can go straight to editing the draft.

Once you have a second draft of your poem, leave it again for a day or two. Sometimes I’ve left poems for years because I couldn’t get them quite right. There’s no shame in that. Sometimes I’ve written 10-20 drafts. And not every poem is meant to reach completion. Some poems are preliminary sketches that precede a master work. Knowing this, and building the tools to improve your best drafts will turn you into a poet who has work that is primed for publication, or at the very least, brings you pleasure and satisfaction.

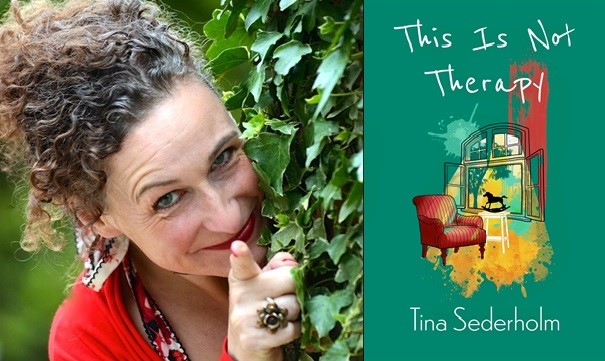

Tina Sederholm is a poet, editor and theatre-maker. Creator of four successful solo shows that have been reviewed as ‘Utterly enthralling’ *****(edfringe review.com), ‘Stunning…beautifully humbling’ ***** (ThreeWeeks) and ‘A Must-See Show’ (Fringe Review), her latest poetry collection, This is Not Therapy, will be published in July 2021.

When not creating her own work, she works as a poetry and prose editor and story consultant. Email tina@tinasederholm.com for more information on ways she can assist you with your latest book, collection, script or poem.