REVIEW: VIV FOGEL’S ‘IMPERFECT BEGINNINGS’

By Stella Backhouse

I was not orphaned at age ten but my father was; and even though I have since childhood mourned the grandparents I never met and felt the gaping void that was their absence, I could never talk about it because my father didn’t, and if he didn’t, what right had I? Adopted at ten months by Holocaust-survivor parents, I imagine Viv Fogel must have been told many times – in answer to who knows what questions – that she’d never understand because she ‘wasn’t there’. I saw it in the stony repetition of those same clipped discussion-enders in her poem ‘On Not Writing the Holocaust’. I shared the frustration of being locked out of the very events that shaped me. No, I wasn’t there; but wasn’t it also true that I’d been there all my life?

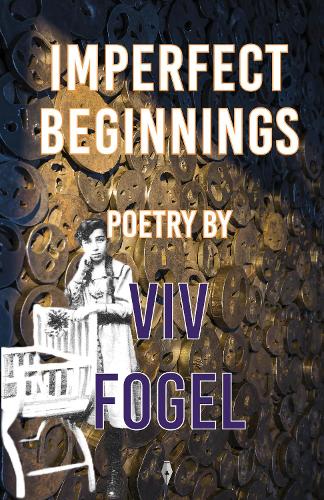

Inherited trauma is a major theme of Fogel’s new collection Imperfect Beginnings, and with a story like hers, there’s a lot of trauma to inherit. If there’s a single defining image here, that image is the heartbreak of mother and child divided. From her very first lines (“For one precious moment/you were my whole world/safe holding and mine/then gone./I was alone”) Fogel returns again and again to the shattering legacy of mother and baby torn apart.

The impact of separation is examined from multiple viewpoints. ‘Coracle’ memorialises the birth mother left without her child. ‘The Switch’ uses the cuckoo-chick’s relationship with its foster mother as metaphor for the conflicted relationships of the adoptee: “Taken to another’s nest, with name and feathers I could not keep,/I became the strange one who did not fit./O cuck-mother – do you not miss your own?”. Later in the book, Fogel regrets the imperfections of her own parenting: “When she was small/I was lonely and sad/too tired to mother pushed/her away/paid for that – ”

Entwined with the theme of separation is a longing for safety, especially the safety of home. ‘Ahmad’s Pool’, a poem about an asylum-seeker, specifically equates the search for safety with the search for maternal reunion. Staggering ashore from a crossing that risked his life, the migrant “collapses trembling into the arms of a volunteer…for a moment he is/in the arms of his mother”. In contrast, Vogel’s own search for safety/mothering is complicated by the fact that her adoptive mother in particular is deeply traumatised by her experiences in World War Two: “Mutti claimed the Nazis butchered her so she couldn’t have babies./I believed her. But she should never have taken me instead./Guilt-sick, she could not keep me safe. She force-fed, fattened me”. In psychological terms, Fogel’s experience of being put up for adoption, then adopted by a profoundly disturbed woman, mean that this is the story of someone who has experienced the Mother Wound twice over.

Nonetheless, difficult issues are raised here. On one level, it challenges our reverential reflex of placing Holocaust survivors above criticism. On another – of course Henriette’s struggles with parenthood should have been recognised. But isn’t parenthood a chance at redemption? It’s noticeable that H, the woman in ‘After’ who chooses to remain childless because of the risk of passing on serious genetic illness, is not redeemed either, but is instead consumed by grief.

To an outsider, Vogel and her family look like people desperate for help. Was it absence of that help that meant that, subverting the image of the asylum seeker on the beach, Henriette remained a refugee who despite reaching the relative safety of Britain, was tragically unable to find home, her dying body “swollen and spongey, the sweat/and bulk of her: stranded gasping her last/on bleak English shingle”? And what does it bode for Britain’s current asylum-seeker policy?

Happily, there is redemption, even if it isn’t for Henriette. In the final sections, Vogel finds joy in her grandchildren and late-flowering peace in a new relationship that is physically and spiritually her home. Significantly, more than one of these last poems is about a house, but now it’s a house Vogel has chosen and chosen to share with Alan. What she is saying, I think, is that she finally has the security she needs to break the toxic cycle of inherited trauma and move forwards. Because after all “What is there to fear?/why return again/to what stops you?”

Imperfect Beginnings is available to purchase online, direct from publisher Fly on the Wall Press, as well as other bookshops and retailers.