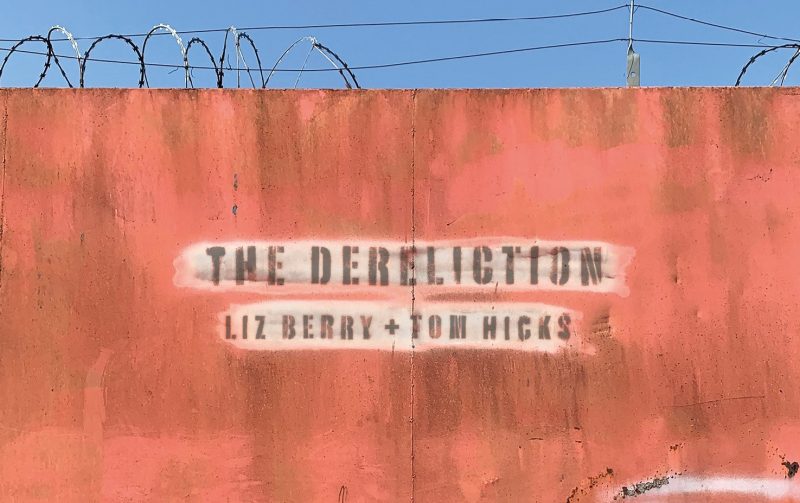

REVIEW: ‘THE DERELICTION’ (LIZ BERRY & TOM HICKS)

Reviewed by Stella Backhouse

“Maybe you’re the same as me/We see things they’ll never see/You and I are gonna live forever…” Half-watching a documentary about 1990s guitar bands, I heard a cultural commentator explain that the power of the Oasis hit Live Forever derived from its pairing of the sublime aspiration of immortality with “a couple of kids from off the estate” who no one expected to aspire to anything.

Liz Berry and Tom Hicks’ alchemical Black Country poetry/photography collaboration The Dereliction is fuelled by this same juxtaposition of intense feeling with overlooked and decaying landscapes. The project, which saw Berry respond with poetry to pictures taken by Hicks on an ordinary phone as he cycled around his local area, has been described by its authors as a ‘democratisation’ of artistic production. But it’s also a democratisation of emotion.

As with artist George Shaw’s paintings of dilapidated garages and discarded pornography around the post-war Coventry council estate where he grew up, Berry and Hicks’ double message is firstly that strong feeling is not something that’s available only to certain ‘types’ of people; and secondly, that a location’s emotional hold is not dependent on conventional beauty. Instead, it’s dependent on association, personal meaning, and contribution to interior landscape. And by exploring human traces left behind, it’s also possible to move beyond the individual to uncover these sites’ own emotional histories, the multiverse record of their role in creating identities that would otherwise have remained concealed.

In his introduction to The Dereliction, R. M. Francis describes the Black Country’s decaying industrial heritage as “ruins and waste grounds left like rusting archipelagos in sooty tides”. A number of Berry’s poems capture these moments of metamorphosis when what we have been told is ugly is suddenly revealed to have magical powers. In Glasshouse Bridge for example, the poet tells how a boy she loved “slipped/through/the cut’s copper looking glass/down into its murky snowglobe of rust” where “his body turned,/thrashing into scales and rainbowed muscle”.

The importance of romantic and sexual awakening in prompting these transformations is a theme throughout the collection. Monmore Green moves from “When I was a lonely girl and still believed in heaven, it was this:/the periwinkle sky over Monmore Green” to “Now I have you I don’t want that blue heaven./I want to enter the underworld through the dirt” and finally to “the earth that holds us/in its darkling heaven of consummation and rot”.

Considering the Black Country’s strong association with heavy industry, many of Berry’s poems reveal an unexpectedly pre-industrial familiarity with flora and fauna. Come Slower So Slow invites readers “down the towpath now hid/with black medick and clover/to lay yourself in, cowslip/and yarrow wild as a bed”. In this cheek-by-jowl of urban and rural – so typical of the Black Country – we experience a collapsing of time, returning us to the earliest days of the Industrial Revolution, when a single lifetime encompassed identities of farm hand and factory worker both; and the parallel creation of ambiguous, non-binary spaces, where new selves become possible. “Here you can be beautiful:” says Berry in Secret Garden. “Monarch or Painted Lady,/abdomen flashing among the parma-violet buddleia”.

In the final poem, Iron Oss, the collection turns on its head. Instead of standing still in space while the past unspools around her, the poet is now moving through the Black Country by train, unspooling herself across the present. “Through the Smethwicks, factories laploved and tumbled,/ the trollied cut with its rainbow of sump oil” she goes until “as we pass, drum your hooves/for Sharon Ann Academy of Dance and Cheer,/a sparkler of joy in the trading estate’s gloom/…the blokes in the breakers yard, smoking in the rain”.

Some years ago, I myself made regular journeys along this very stretch of line. Together with Tojo’s Bridge (if you know, you know) and a trackside house in Oldbury sporting paintwork in not one but two particularly lurid shades of green, the Sharon Ann Academy and the smokers, lounging like lords on their manky old sofas, were landmarks I always looked out for. I miss those trips; but to see a little part of them affirmed in poetry somehow affirmed a little part of me. Thank you, Liz and Tom.

The Dereliction is available for online purchase from Hercules Editions.