REVIEW: ROZ GODDARD’S ‘LOST CITY’

Reviewed by Stella Backhouse

Two days after Russia invaded Ukraine, I was researching Roz Goddard’s chapbook Lost City in preparation for writing this review. As part of that, I came across a YouTube video of the collection’s online launch in November 2020. England’s second national coronavirus lockdown had just begun, and while Goddard’s poems had not been written in response to the pandemic, hosts and guests were musing on the aptness of her visions of urban emptiness and abandonment. Those were scary times; the perversity of now describing them as ‘innocent’ does not escape me. And yet less than eighteen months later, lines like “though [The President] cannot read he carries/the world’s greatest text on love…He thinks we’re like him. We’re not” are unnervingly relevant to a new horror – one we had no scent of then.

Although Goddard has said that Lost City is set in an imagined but contemporary coastal city, and examines “the impact of post-industrialisation and the effect of toxic political leadership on the collapse of cities and communities”, the legacy of other possible histories is also detectable in the text. Flight from war is suggested by the confession that “It’s not what we left in our rush to leave…journeys in failing cars/over deserts with people we do not love”; environmental catastrophe by repeated reference to floodwater; something ominously unnamed by the voice that is “Looking for my brother, softly, wearing gloves,/I shifted bodies until I saw him”.

This sense of an unstable past is also conveyed by the disconnect between official narratives mouthed by ‘The President’ and lived experience of his rule. We are told that “The President,/our shepherd, loved the word of God” but also that “The President’s men came/shouting for my husband…They stood as giants in a backyard tent,/ammunition glittering.” His visit to the City, when “Bypassing empty ballrooms where the floors are gritty/and smell of rabbit, he muses on the benefits of emptiness” is reminiscent, in its contortions, of 1984’s ‘War is Peace; Freedom is Slavery; Ignorance is Strength’.

Each poem is spoken by a different character, some of whom appear more than once. What all of them share is an unsettling stoicism and neutrality in the face of atrocity. ‘The Ambulance Driver’ for example speaks of how “When we arrive the dead are still warm./Silent children, who never sleep/and witness everything, attend there” but also of his desire to find relief through sex. His wife “understands this need,/finds the heat and my desperation another/thing to cope with. She worries the city is drowning.” These are poems about humans’ relationship with catastrophe – resilience and the drive to carry on; but also, through the repeated presence of the Tour Guide character, the human urge converts even this place of “windows blown to standing snow” into art. It’s not absurd to wonder if the Tour Guide is actually Goddard.

I found myself disorientated by Goddard’s coyness about Lost City’s geographical location. Although she stated at the launch that she was partly inspired by the American Rust Belt city of Detroit, her Birmingham/Black Country heritage inevitably had me comparing her work with the last collection I reviewed. But while The Dereliction’s theme is a similar one of urban decay, its setting is unmistakeably – and celebratory – Black Country. Yet at the same time, Goddard’s vagueness also intrigued me: it signalled possibility. Such as – what if Lost City is not a geographical entity at all? What if Lost City is the life-force inside each one of us, gradually ageing, grudgingly succumbing to the wreckage wrought dementia and physical disintegration, reluctantly winding down to its end?

In particular, the poems ‘The Lover’ with its memories and where-did-our-youth-go yearning (‘How we sneaked away and the receptionist/prim in her blouse, watched…Didn’t we have years/lined up in reverence?’) and ‘Citizen’ with its realisation that material possessions count for nothing in the end, made me speculate on whether Lost City could actually be the lament of a dying mind for the life that’s deserted it. If so, then Goddard, like Dylan Thomas in ‘Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night’, advocates the dignity of defiance: “Let us be foxes treading lightly/noses to the drama of a shining night,/holding stars in the emptiness.”

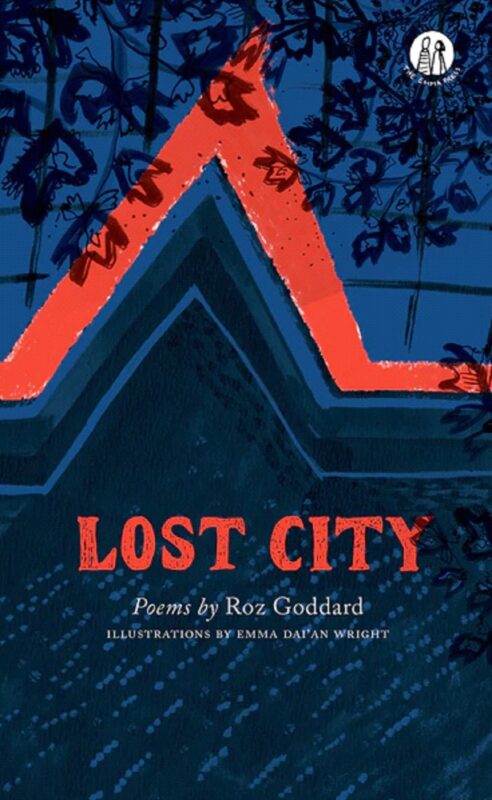

The Lost City is available for purchase online direct from The Emma Press or other bookstores.