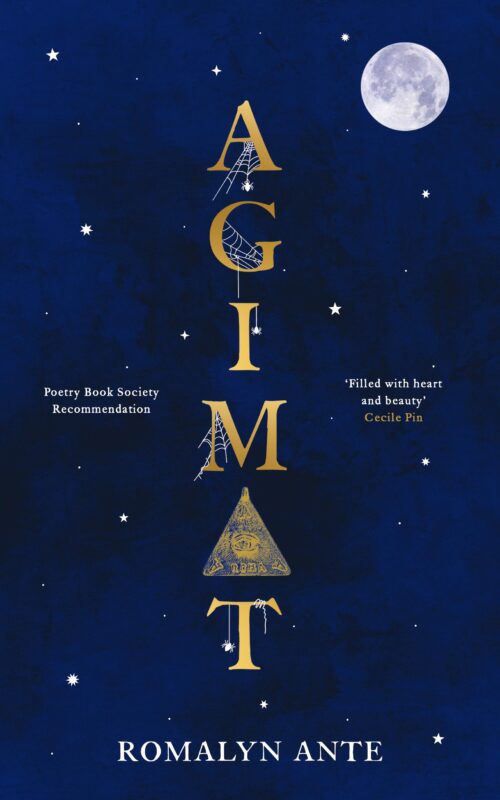

REVIEW: ROMALYN ANTE’S ‘AGIMAT’

By Stella Backhouse

What does it sound like, the sound of a train that’s gone? Back in pre-digital days, larger railway stations often featured split-flap departure boards whose flaps, as they rapidly slapped against each other after every post-departure re-set, transmitted a message of unmistakeable finality. Yet at the same time as they unheedingly sealed the fate of breathless latecomers, they also released something else to chatter in the air around those left on the platform: the ghostly imprint of a journey that might have been.

I’m guessing it’s no coincidence that Agimat, Romalyn Ante’s recently-published second collection, contains many poems about transport – foot, as well as rail and road. Neither, I think, is it coincidence that in most of them, the traveller’s route is shrouded in mist, precipitation and shadows, with the destination too remaining ambiguous. In Agimat, Ante’s world is one of constant doubt about the chosen road, constant comparison with roads unchosen whose potential nevertheless pervades the poet’s actuality. ‘Looking up at the 700-year-old tree inside Kayashima Station’ is perhaps the culmination of these tensions, in which “the future’s already a gate half-closed” and the poet’s head is “turning left/and right, scanning for the train,/not sure if it’s yet to arrive/or has already gone”.

The paralysis risked by longing for the past is evident in studies of the poet’s father, who in the alternative reality of his homeland “wears the pangíl ng kidlat;/it gives him healing powers”. In Wolverhampton, however, he “works in a care home/where a resident chucks his blue pills/into a fish bowl and strikes my father in the chest”. On his break “he spreads a blanket/on the Stock Room floor, lies in a space/as wide as a grave”. More problematically for the poet, the past returns in traumatic guise when her budding relationship with a man of Japanese lineage disturbs her family’s memories of Japan’s brutal World War II occupation of the Philippines.

Hauntological ideas are actualised throughout the collection. The past continually invades and shapes the poet’s understanding of the present, posing questions about the linearity of time. In both ‘Hisahi’ and ‘Highschool-Crush Haibun’, two poems that seem to reference a youthful romance with a basketball player, the past and present co-exist in the same moment. ‘Hisashi’ blends memory with the present to create a seamless dreamscape where “a ball swishes through a net and I’ll turn –/to find commuters spilling from Galton Bridge”. In ‘Highschool Crush’, the poet haunts her own life even as it happens, “trail[ing]in the wake of your shadow like the ghost of a plastic bag/in a treetop”.

As in the poet’s nebulous journeys, describing a pure present seems almost impossible. This difficulty also applies to linguistic purity – especially, perhaps, for an English-language poet whose first language is not English. The evocative shapes of the pre-Hispanic Filipino script known as Babayin appear throughout the collection. The search for uncontaminated language also involves the poet’s infant nephew, whose fascination with the letter ‘O’ seems hardwired. He reproduces the symbol of a hungry mouth so many times that the paper he writes on gives way.

Equilibrium of a kind arrives at the end of the collection. In ‘Touchstone teaches Mebuyan’, the poet acknowledges the relativism of “a life that is forever shifting./Move and everything else moves with you” but also embraces the joy of those who “seek happiness in this lopsided world, knowing/it is only the ground that keeps us aloft”. In the longer poem ‘Breathe’, yearning for the past is channelled through the medical imagery of Ante’s nursing career. Likening herself to a patient with lung disease, she acknowledges the corrosive potential of attachment to the past: “what’s inside is decay – a mosaic of rot/colonising a bough like the ruins of a war/my mother speaks of in another tongue”, but finally accepts that “What goes out is gone./ What we long for does not come back”. However, while the poet may have made her own accommodation with the past, echoes of ‘Breathe’ still reverberate through the concluding poem, ‘Fire Flower’. Here, the poet speaks to her unborn child: “You are so dainty,/so scarce,/so breakable by breath.” The cycle is preparing to start over. Even a life that has not yet begun will eventually have to navigate a course through the ghosts of its past.

AGIMAT is available from all good booksellers, including Waterstones and Verve Poetry Bookshop.