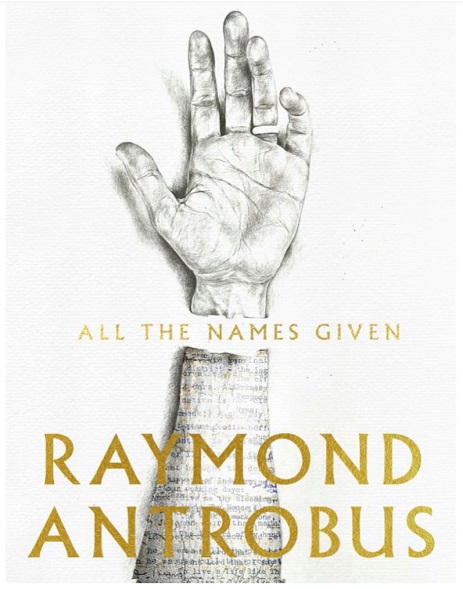

REVIEW: RAYMOND ANTROBUS’ ‘ALL THE NAMES GIVEN’

Reviewed by Stella Backhouse

“You never see X and Y in the same room at the same time” is an ambiguous phrase. It could mean X and Y can’t stand each other; paradoxically, it could also mean the disdain is just a distraction and actually X and Y are so alike that that X could be Y in disguise. But within Raymond Antrobus’s 2021 collection All The Names Given, the poet’s description of the antipathy between his dreadlocked Jamaican father and his white British maternal grandmother, the possibility of a revelatory third meaning opens up.

Antrobus’s relatives’ mutual dislike dated from their first meeting: “he was drunk and he didn’t like the way she looked at him…and my grandmother shouted You black devil!” It never mellowed. So, when Antrobus concludes that “I never saw/my father and my grandmother in the same room my whole life”, latent discomfort is lurking. And as the vessel containing the heritage of father and grandmother both, perhaps that discomfort springs from an awareness of Antrobus himself as the room and his ‘whole life’ as an exercise in trying to arrange into a coherent whole two furiously warring sets of internal furniture?

If Antrobus’s earlier collection The Perseverance explored his relationship with his father, All The Names Given shifts the focus to his mother and the unusual surname they share. But this is no neat division of self. There is constant bad-tempered jostling between the ragged edges of black and white pasts. Visiting their ancestral Cheshire village of Antrobus (meaning ‘between the trees’), the poet and his mother are asked if they’re descended “from/Edward Antrobus, (3rd Baronet)/slaver, beloved father/over-seer, owner of plantations/in Jamaica”. Contemplating ‘Plantation Burial’, an 1860 painting by John Antrobus, Raymond begs his partner to “tell me if I’m closer/to the white painter/with my name than I am/to the black preacher”. The word ‘shade’ – with its long vista of meanings including ‘ghost’, ‘shadow’, ‘skin tone’ and ‘disrespect’ – is important here. “I can’t mention trees” says Antrobus “without every shade of my family/appearing and disappearing”.

Antrobus is also a Deaf poet, so in an intersectional collection like this one, the idea of part of the self being silenced has double resonance. These frustrations boil over in ‘Royal Opera House (with Stage Captions)’. Watching A Man Of Good Hope, a play about black experience by the white playwright Jonny Steinberg, Antrobus observes the audience celebrating the protagonist’s triumph over adversity: “everyone…Black/white, whatever, rises to their feet and shouts and hollers and/claps and cries and none of the silences, none of them are filled”. What Antrobus has experienced as the noise of narratives clashing has paradoxically become silence.

‘Royal Opera House…’ is accompanied, as are other poems and spaces between poems, by ‘close captioning’, a technique that Antrobus has adapted from the work of Deaf sound artist ‘Christine Sun Kim’. Antrobus explains that Sun Kim “rewrites captioned text from films in order to revise the listening experience from hearing centric to Deaf centric…ask[ing] ‘does sound itself have to be a sound? Could it be a feeling, emotion or an object?’” Parentheses such as “sound of self divided” and “sound of mirror refusing reflection” create spaces where meanings of noise can be reimagined and versions of silence can be heard as rich narratives in their own right.

In the final poems, resolution appears through a new relationship and new beginnings. Unburdened by anxieties about the relationship between his identity and the past, Antrobus’s American wife-to-be is able to accept him as the person he actually is. He tells her “The first time you told me you loved me/I didn’t say it back…I needed to hear it in the morning/hear it said when neither of us/could be anyone/except who we are”.

Accepted into wholeness, the newly-weds sprint to the Mississippi river, completing a circle that began in the opening poem with the emergence of Antrobus’s late father from the river in a dream – which itself is a reprise of the earlier poem ‘After Reading Deaf School by the Mississippi River’. Later, during love-making, Antrobus finally reaches a place that is not an in-between. A place “outside myself/It’s the silence that stills/the noise in my eyes./Reader, this is the place/I try to take you/when I close them”.

All the Names Given can be purchased from various book retailers, including Waterstones (in-store and online) and Bookshop.org.