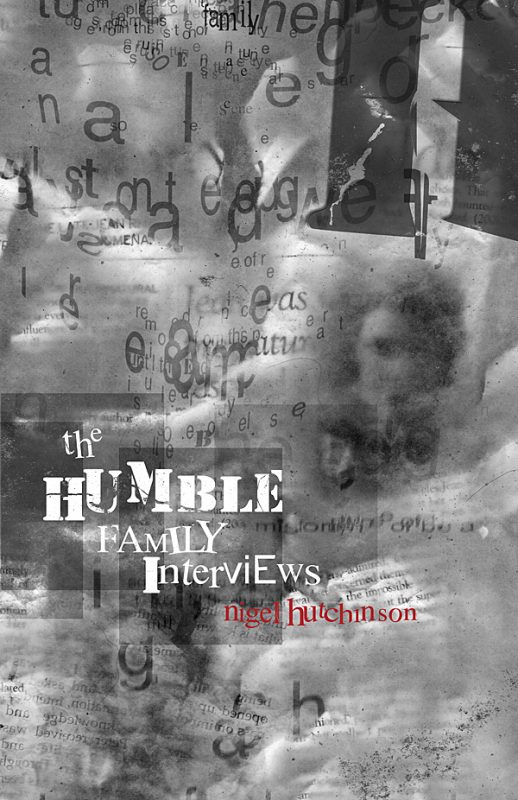

REVIEW: NIGEL HUTCHINSON’S ‘THE HUMBLE FAMILY INTERVIEWS’

THE HUMBLE FAMILY INTERVIEWS BY NIGEL HUTCHINSON

CINNAMON PRESS

ISBN: 978-1911540007

£8.99 / 72 pages

Reviewed by Stella Backhouse

A word of warning, if you’re thinking of buying Nigel Hutchinson’s intriguing début collection The Humble Family Interviews as a Christmas present for the poetry-lover in your life: these are poems that require the reader to do quite a bit of work. That’s not to say the book’s not enjoyable: its starkly vivid imagery conjured from startling juxtapositions of simple, everyday words linked by rhythms of plain speech is a thing of unexpected delight. But it will take more than one reading to absorb it fully.

Hutchinson embraces a variety of forms. At the collection’s heart are two extended sequences of modified found-poetry, ‘The Humble Family Interviews’ and ‘Accidents of this Game’. Around them are arranged stand-alone poems about nature, fragments, time and art – indeed, it’s a collection notably rich in artistic inspiration, with a number of poems, including the title sequence, produced in response to paintings by the likes of Marc Chagall, Jan Brueghel and, in particular, the Coventry-born, Turner Prize-nominated artist George Shaw. Looking for literary precedents, I caught glimpses of the Book of Genesis, the Gospel of John, T S Eliot, W H Auden, the modernist Spanish poet Federico Garcia Lorca, an obscure Gaelic language primer and…scissors paper stone.

This eclectic collage of influences reflects, I think, Hutchinson’s desire to explore the roots of knowing: how – quite apart from their dictionary definitions – words and images arrive at those frames of personal meaning that flash through the movie reel of every mind; and how we communicate those meanings, either through art or through language. A major springboard for this exploration are the paintings of George Shaw.

Shaw’s best-known works are his depictions of Tile Hill, the Coventry council estate where he grew up. He is on record* as saying that “Far from being paintings of a place, they’re really self-portraits” – inviting us to reflect on how our own surroundings, particularly our childhood landscapes, contribute to the construction of identity and meaning. By rearranging words found in the text accompanying the exhibits at Shaw’s 2011 exhibition at the Herbert Art Gallery Coventry, Hutchinson tries to capture associations within individual minds, interpreting familiar scenes as both known and strange: “I remember feeling, probably/a bloke in the background/another pale ghost.”

The other extended sequence, ‘Accidents of this Game’ applies similar techniques to lessons from a Gaelic language primer of the 1930s. By restricting vocabulary, Hutchinson inflates meaning; the poems have a modernist boldness, their simple lexicon forcing significance out of mere proximity, reminding me of Mondrian’s paper art, The Snail. This mapping of new connections is part of Hutchinson’s mission. The line “I am the day and a knife” kicked round my brain for days before I hit on “I am the way…and the life” from John Chapter 14. Meanwhile “The horse is as sure as death,/death is as liberal as time,/time is faster than a yacht” was immediately scissors paper stone.

And why not? Scissors paper stone is not high art, but it’s a volume in the library of my mind, as it is in most people’s, and it’s available as a point of reference. In the interview quoted above, George Shaw highlighted the way we both create art and are created by it. His early influences, he said, came from the popular culture that surrounded him – TV sitcoms and tabloid newspapers – because “no artists came to Tile Hill and painted Tile Hill. That wasn’t where art was to be found.”

Hutchinson’s stand-alone poems amplify this point that art is not a cordoned-off entity: anything that has meaning – high culture or low – can feed into it. So while ‘The Physics of Falling in Love’ is an appreciation of an established artwork, ‘The Art of Painting Suburbs’ imagines a trio of celebrated artists painting blocks of flats and drinking in the pub; ‘Beached’ records an ephemeral encounter that could be become embedded in the mental landscape of walks along the beach; and ‘Down the pub’ acknowledges that “songs on the jukebox that say it all, your life in three minutes” may be regulars’ only opportunity to hear their lives told as poetry.

The Humble Family Interviews is an intriguing and quietly fascinating collection. You may never have suspected that somewhere exists “the boy pouring the cat from the bag” – but he does, and Nigel Hutchinson has the map that will get you there.

The Humble Family Interviews is available online from Cinnamon Press and Waterstones.

* George Shaw: I woz ’ere (Part 2), a film by Jim Turner for Herbert Media Productions, 2011

This interesting film is worth a watch and can be found here. It features a very unpretentious Shaw talking about art in an accessible and straightforward way. One intriguing point to consider is how much he would approve of Nigel’s responses to his work – at one point he says, “It isn’t anybody else’s story. It’s mine.” But by choosing to put his paintings in the public domain, is he giving his audience permission to make them part of their own story? Discuss!