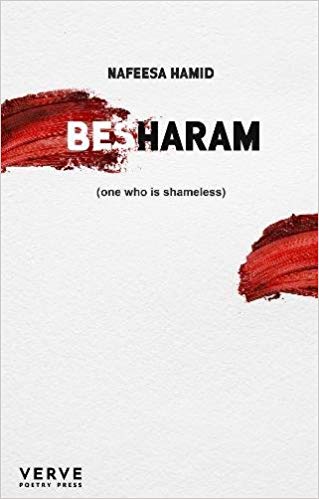

REVIEW: NAFEESA HAMID’S ‘BESHARAM’

BESHARAM BY NAFEESA HAMID

Verve Poetry Press

ISBN: 978-1 912565 05 4

£9.99/108 pages

Reviewed by Stella Backhouse

What intrigues me most about Nafeesa Hamid’s début collection Besharam (One who is shameless) is the innovative way she uses language and imagery to express her conflicted relationship with her body. Innocence was snatched from Hamid in the most brutal way. Abducted from outside her Birmingham home at the age of nine, she was driven around the city in the back of a stranger’s car, subjected to sexual assault and finally dumped on a nearby street hours later. Besharam is, in part, a reflection on the enduring legacy of this shattering event.

What intrigues me most about Nafeesa Hamid’s début collection Besharam (One who is shameless) is the innovative way she uses language and imagery to express her conflicted relationship with her body. Innocence was snatched from Hamid in the most brutal way. Abducted from outside her Birmingham home at the age of nine, she was driven around the city in the back of a stranger’s car, subjected to sexual assault and finally dumped on a nearby street hours later. Besharam is, in part, a reflection on the enduring legacy of this shattering event.

Although the book is divided into two sections – ‘Body’ and ‘Mind’ – this is to some extent a false dichotomy. Because of the assault, part of Hamid’s psyche remains arrested at age nine, “part jawan*, part still child, still nine” (poet’s italics). Her body, meanwhile, continues along its path of physical development. The result is a disconnect that is at the same time profoundly connected. Returning to the theme of abduction, it’s as if Hamid’s “woman body” has now become the hijacker, taking her to places she feels unready to go.

Hamid portrays “Womaness” as an alien entity that has colonised her body against her will. Her “Woman” is a burden she longs to shed, an illness requiring treatment, an independent being that, like a mangy parrot on her shoulder or a querulous inner child, demands constant curation. Unable to show emotion, she laments “the state of my woman”; meanwhile the doctor informs her that “part of [her] woman is ill”.

The language Hamid uses for bodily changes also reveals ambivalence unresolved. To describe adulthood, she deploys the language of childhood: to come of age is “to woman”; the purpose of female sexual maturity is “to baby”. These unworldly, intentionally simplistic verbs betray, perhaps, a secret fear of induction into details.

Born in Pakistan and brought to Britain at age four, Hamid’s sense of disorientation is further amplified by the shocking domestic violence perpetrated by her father and also by a life caught between conservative Islam and the liberal West. Under the surface, however, these outwardly opposing discourses are shown to have features in common: both view the entire concept of ‘woman’ as problematic. Coupled with Hamid’s experience of her body as stranger, the result is a serious crisis of identity.

This expresses itself in experimentation with different sexual orientations, promiscuity (the poem ‘Ice Cream’ instantly transported me to the scene in Fleabag Series Two where Fleabag tells the therapist “I’ve spent most of my adult life using sex to deflect from the screaming void inside my empty heart”), eating disorders and disengagement from education.

None seems particularly successful, and indeed, much of the book’s ‘Mind’ section is devoted to detailing Hamid’s interactions with mental health services. But the real conundrum is that while womanhood itself is viewed by society as a form of insanity, rejection of womanhood is also evidence of the same. So while Hamid’s lover is “terrified of all my Womaness/breasts too big, hips too wide, mind too mad”, her psychiatrist is simultaneously prescribing medication to treat the pathology of not “want[ing] to woman any more”.

The window of acceptable woman is a narrow one. For Hamid, the only solution to being “too little woman./ Too much” is an impossibility: a return not just to childhood, but to “to my mother’s womb/drenched in amniotic fluid” so that she can start again. If it is anything, this sobering, rather desolate book is a cry against the rigid, culturally-prescribed mind/body, man/woman, adult/child dualities that confine and restrict us, and a plea for freedom to be the people we were born to be.

*jawan: of age, mature

Besharam is available online from Verve Poetry.