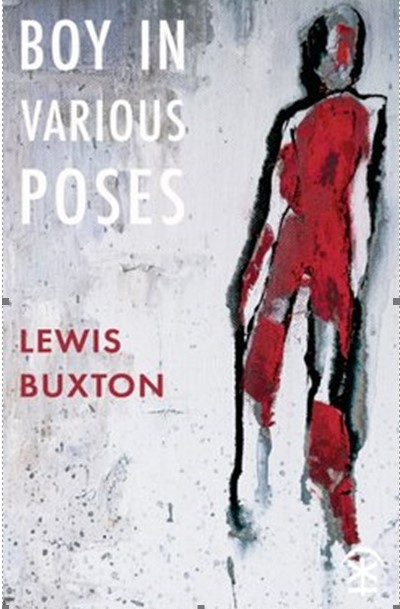

REVIEW: LEWIS BUXTON’S ‘BOY IN VARIOUS POSES’

By Stella Backhouse

In Lewis Buxton’s 2021 collection Boy in Various Poses, two strands of poetry converse with each other across the divide of the spine. On the left-hand pages hang short rectangular prose poems whose titles all start with ‘Boy’ or ‘A Boy’ or else bundle up the word ‘boy’ inside some other word. Facing them from the right-hand pages are poems more varied in form, but also dealing mostly with life experienced while male. The effect is something like an art gallery, where pictures that explore the different ways to be a boy spark thoughts and responses in the gazing audience. ‘A Boy with Haemorrhoids’ for example, seems to provoke ‘Butchery’.

The insistent repetition of ‘boy’ in every title acts as a kind of frame for the left-hand poems; but its definiteness and monosyllabic irreducibility contrast with the mercurial portraits of boy-ness celebrated by what is held within. It’s as if Buxton is taking the reader beyond high walls made of bricks marked ‘boy’ to show them the private gardens they enclose. In fact, many of these poems (both left- and right-hand) read as if they began life in the privacy of a bedroom where, alone or with a sexual partner, boys can shed gender expectations and experiment with other selves. The first poem, ‘Sevenling’, economically introduces the recurring motif of conventional masculinity as a costume that can be cast aside to reveal a more authentic self hidden beneath. From “I dress like my idea of a boy:/creased trousers & pea coats & good shoes,/things the world expects of me”, it moves to “I’d like to paint my eyes & nails…dropping/expectations like a coat on a dance floor”.

These are poems about the heavy toll exacted on men by the strictures of traditional masculinity, many of them couched in noughties culture (Buxton was born in 1993). ‘A Boy Does a Magic Trick’ imagines a different ending to illusionist David Blaine’s forty-four day suspension of himself above the Thames in a small Plexiglass box in 2003: “Boys know sleight/of hand so people are always looking somewhere else/as their houses of cards fall apart…failing to escape the/box he has locked himself in…He is gasping but is so magic that no one/comes to help him”. In between, brilliant glimpses of other possibilities flash out: “He looks at his blue, blue, blue/shape and mimes all possible movement, reaches/bends, dances. (‘A Boy in a Blue Suit’).

Buxton turns to sport, a subject not often seen in poetry, to explore how men act out their relationship with their bodies and with masculinity. In ‘Boys Do Push Ups’ an ageing sportsman cannot shut out “The rugby coach in his brain [who] shouts at him/to go all the way to the ground and back up again”. ‘Scrum’, ‘Advice from the Quarterback’ and ‘Water Weight’ expose the paradoxical male culture of fetishising match-fitness while simultaneously branding as weakness any care for other aspects of physical and mental health. The image of masculinity as frightened rabbit disguised beneath a uniform (in this case of hyperdeveloped muscle) appears first in ‘Field Dressing a Rabbit’ and again in ‘Frightened Rabbit’ where, along with “bulletproof denim” masculinity is “a coat of muscle”, “shrugged” on with an inevitable, almost visible ‘what choice do I have?’ gesture.

As I suggested above, the idea of masculinity as clothing than can be discarded recurs throughout the collection. Second-half poems where the boy strips down to his underwear or shaves off his beard to let the air caress his skin are symbolic of acceptance of a truer self. Some readers may feel Buxton occasionally goes too far. Men have for centuries used reproduction as a way to control women’s bodies; imaginary male pregnancies including (in ‘A&E’) the almost-comical speculation that a man whose girlfriend inserted an unnamed foreign object into his rectum did it so he could “feel like he was giving birth” could be seen as disrespecting this. I doubt Buxton means it that way. Rather, these are playful poems celebrating how, within the liberating atmosphere of an intimate relationship, it’s acceptable to let down your guard. The final poem, ‘A Boy Gets Married’ (in a red dress) is his joyful culmination, bookending the first poem, sharing the possible.

Boy in Various Poses is available to purchase online, direct from publisher Nine Arches Press, as well as other bookshops and retailers.