REVIEW: KATY WAREHAM MORRIS’ ‘MAKING TRACKS’

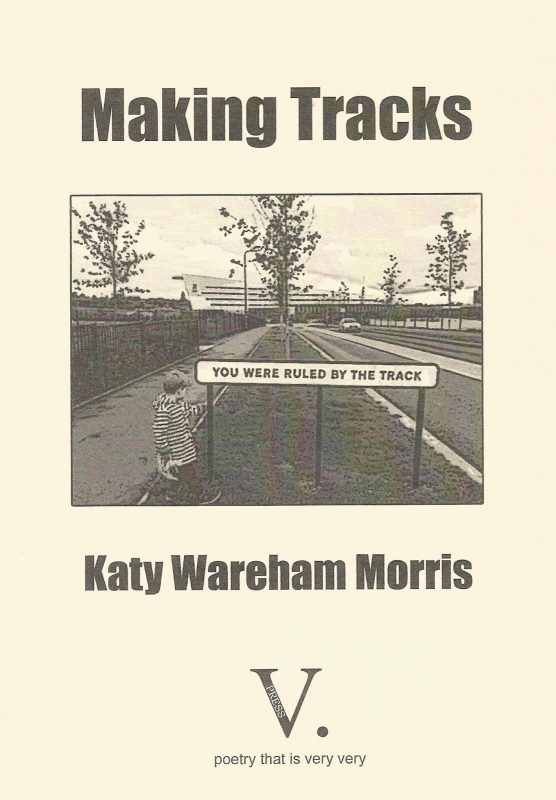

MAKING TRACKS BY KATY WAREHAM MORRIS

V. PRESS

ISBN: 978-1838048808

£6.50/36 pages

Reviewed by Stella Backhouse

Towards the end of Middle England, the third book in Jonathan Coe’s eponymous trilogy, Benjamin Trotter and his father Colin visit the site of Birmingham’s Longbridge car plant, where Colin used to work. It’s early 2016. The factory, which closed eleven years before, has been demolished and the site is now a shopping centre. Staring uncomprehendingly round a cathedral-sized branch of Marks and Spencer, Colin – whose mind is beginning to unravel – struggles to understand where he is. “I mean, a building isn’t just a place, is it?” he afterwards asks his son. “It’s the people. The people who were inside it.”

The Longbridge factory and the people who worked in it are also the subjects of Katy Wareham Morris’s 2020 pamphlet Making Tracks. In it, she both expands on Coe’s point about lost community (“We should be thankful for the UK’s leading/regeneration specialists and all its council partnerships for supporting/community values. It boasts of a whole new community but that/brownfield was a community – where did everyone go?”) and focuses right down on the experiences of a single worker: her father. Dilating and contracting like a beating heart, Wareham Morris’s dizzying perspectives are in themselves a commentary on the developers’ promotional blurb about “putting the heart back into/Longbridge”.

To capture the multiple facets of memory, the collection deploys a variety of techniques including found poetry, shape poetry (I particularly liked the depiction in ‘Empty Shells’ of the famous conveyor belt bridge that used to span the Bristol Road) and verbatim extracts from interviews with Wareham Morris’s father. The factory’s hundred-year history, its wartime record as maker of munitions and tank parts, its reputation as both innovator and locus of industrial strife, as well as its role in creating group and individual identity – all are covered here. The preservation of real-life testimony and witness to a lost way of life means that, in some ways, Making Tracks functions as much as social history as it does poetry.

But not in every way. Weaving through Making Tracks are numerous references to the Romantic poet William Wordsworth, a copy of whose works, given to Wareham Morris by her father when she was a child, inspired her own love of words. In juxtaposing Wordsworth’s well-known nature poem ‘I wandered lonely as a cloud’ with the noise and automation of the shop-floor, Wareham Morris reflects on the survival, even in a mechanised environment, of the human urge to convert experience into art.

The unpunctuated ‘Vehicle Scheduling (Fragment V)’ for example, has a worker’s unofficial tea-break continually halting the track. By the use of repetition, Wareham Morris builds increasing momentum through successive stanzas, before each one comes to a juddering halt with a heavy-printed “stop”. Beyond the clipped, repressed final line “dispute meeting ain’t solved it (planned it?) right we’re off”, the hollow clang of men downing tools is almost audible.

After their unsuccessful visit to Marks and Spencer, Colin Trotter complains to Benjamin that “it’s just…fancy clothes and Prosecco bars and bloody…packets of salad. We’ve gone soft, that’s the problem”. His disgruntlement ultimately translates into a leave vote in the upcoming EU referendum. But Coe also hints at another anxiety, this time an unspoken one. In the shop, Colin is “confronted by row after row of stockings, bras and lacy pants…If he had been expecting to find the…testosterone-fuelled atmosphere of the old Longbridge assembly track, his confusion was understandable”. Is this, perhaps, the root of what he meant by “gone soft”? The feminisation of culture? The lurking fear that men are becoming redundant?

It’s a dilemma that’s also detectable in Making Tracks. Running alongside the impersonal, masculinist/managerial language of production, the very human story of a marriage in trouble is playing out. The details are vague, and I don’t wish to speculate on private grief; but in the Venn diagram poem ‘You and Him’, Wareham Morris depicts herself as a woman essentially trapped by masculinity in crisis: the father, his masculine credentials secured beyond doubt by his employment history; and the husband, “needing me to tell you who to be”. Her dad, I sense, emerges the winner. Which brings me to my final thought: I greatly enjoyed Making Tracks – but I do wonder what loss Wareham Morris is really mourning.

Katy’s Making Tracks pamphlet is available for purchase online from V. Press.