REVIEW: JULIA WEBB’S ‘THREAT’

Reviewed by Stella Backhouse

Something called “the big pushchair” makes several appearances in Threat, Julia Webb’s 2019 collection about growing up in rural Norfolk. The pushchair is not the subject of any poem; instead, it’s a background figure, its mentions all in passing, its bovine functionality a stark contrast to the real meat of dysfunctional family life going on around it. In ‘She was a biscuit barrel…’, its stoic trundling home of the weekly shop goes unappreciated as “in the other room the TV blared/the shopping was defrosting in the pushchair’s tray/the kettle was still whistling on the stove”. In ‘Nothing could be done’, it is the dumb scaffolding of lumpen routine: “their rows walking into town…three children, all of them mistakes/in the big pushchair or trailing behind.”

All of us, lurking in the back of our consciousness, have a big pushchair: some taken-for-granted piece of infrastructure from our childhood landscape, its origins unquestioned, the private connotations of its consensually-agreed name understood by everyone inside the family and no one outside it. The process of growing up is in some ways the process of interrogating these fixtures, of discovering where they came from and why, of revealing them as contingent. But what if you never ask the questions? What if you go on accepting everything as simply inevitable?

Threat is what happens when an entire society never asks the questions. It’s about growing up in an inward-looking, white-working-class monoculture centred on the family, on the pub and on sex. Middle class aspiration gets short shrift. Literature is “Me – book open on the table reading/someone, somewhere, in a headlock/someone’s lights punched out”. Music is “the DJ you used to date play[ing] your favourite Steve Hillage, the one you ask for every week”. The purpose of school is to “keep us in/ignorance of the things that really matter, and/never praise us, never/show us the greener pastures”.

In this world of limited options, the bus station’s rancid toilet block is desperately pressed into service as a locus of intense teenage significance: “Meet me at Damp-Cement, Izal, Jeyes Fluid,/Meet me by the cracked sink and the broken soap dispenser”. More ominously, a menacing, almost casual sexuality permeates almost every social interaction. Adolescent boys are horses, “eating your best border flowers/his head in next-door’s bush”. Girls find their bodies routinely subjected to a disquietingly sexualised gaze: “and he says when you are 16 I will take you to the woods/I can’t resist”. The girl’s feelings of course don’t come into it – because this is a society that is its own mirror.

There are casualties. Something bad has happened to the poet’s brother, perhaps because he couldn’t follow the prescribed script: “Did the world always fit wrong, like those days you pull a sock on and off and on and off because the seam won’t sit right. Was your view a different colour?” The poet finds it difficult to deal with her ageing and increasingly querulous mother. The distorted, oddly-Caribbean inflected ‘no sister no’ describes the fallout from her sister’s refusal to attend the mother’s funeral.

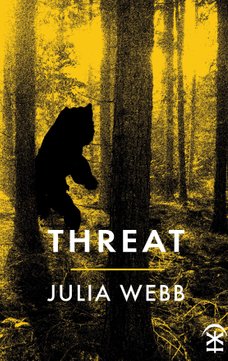

Threat is a lesson in how concentric rings of claustrophobic landscape – the body, the family, the town and community encircled by the dark and forbidding Thetford Forest – shape a parallel landscape of the mind. Webb fears she is permanently scarred by her formative experiences: “Weeks and months go by now where I barely say its name/but its language lives inside me”. The damage done to her brother occurred because “A mother should build a fence/to keep the forest out,/not invite it in to mind the kids”.

But ultimately, Threat is about escape. Webb finds uses for her body that are not unsatisfying sex. In the concluding poem, ‘All the Women’, she is in a different place and has joyfully embraced narratives other than those she was born into: “There are books, books galore on eBay and in libraries…the women…are writing their epic poems on the inside of my skin…I open my book beak and inadvertently sing”. And here’s the thing: that song is the real threat – because threat runs both ways. The treat Webb knew as a child came from within; but threat itself can be threatened by getting outside it and speaking truth.

Threat is Julia’s second collection. Both this and Bird Sisters are available to purchase online from Nine Arches Press.