REVIEW: JANE BURN’S ‘ONE OF THESE DEAD PLACES’

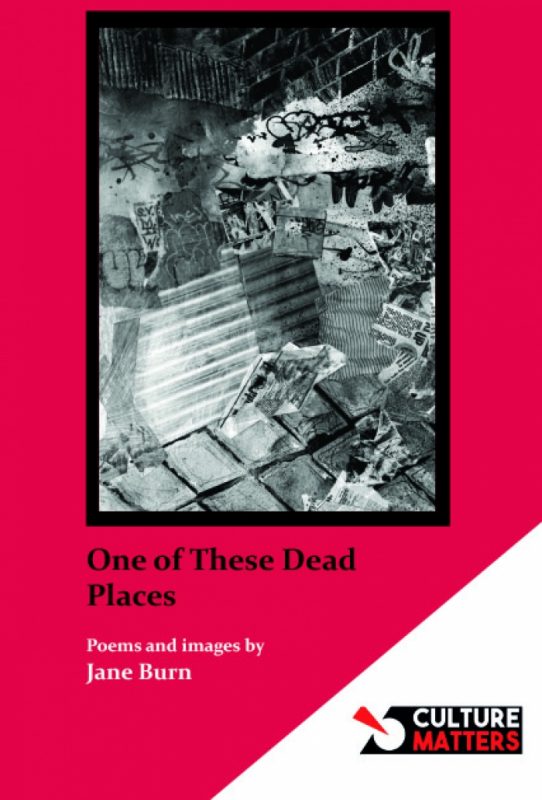

ONE OF THESE DEAD PLACES BY JANE BURN

CULTURE MATTERS

ISBN: 978-1912710072

£8.00/115 pages

Reviewed by Stella Backhouse

For a posh bird, sat here writing poetry reviews in leafy south Cov, I have more affection than you might imagine for the pit villages of the Dearne Valley. Working in Sheffield hospitals, I traced the tracks of coal dust sealed within skin and registered the pride that named Elsecar Main the “finest bloody pit in t’world”. I’ve even donned a miner’s helmet and descended to the bowels of a working pit: Rossington Colliery, south of Doncaster – gone now, like all the rest. So I have a lot of sympathy for Jane Burn’s lament for a lost industry and a lost way of life in her 2018 collection One of These Dead Places. But though Burn clearly loves the valley of her birth, I’m not sure how much it loves her back.

Because the thing about these tight-knit, monocultural communities is – they’re wonderful as long as you fit in. It’s when you don’t fit in that the problems start, and in these poems, Burn knows herself for an outsider. It begins in childhood, when she considers herself “too ugly and strange” to aspire to marriage, and is discouraged from reading because her mother believes it “would just make me fatter”. By the time of the 1980s coal strike, when her father was no longer employed in the pits, she finds herself surrounded by hostile classmates who could see no explanation, other than scab labour, for his continued working.

And while no one should assume that ‘miner’ was synonymous with ‘uncultured’, formal education becomes less relevant when boys’ working lives – like those of generations before them – are mapped out from birth, and women’s careers are secondary considerations: “we could work in the factories – sewing,/or steel. Shopworker, maybe a typist be.” A lover of books, Burn describes “leaving school still not sure what a noun is” and her surprise upon learning that “anyone can be an archaeologist”.

The real heartbreak is not that King Coal has been deposed: even without Margaret Thatcher, our twenty-first century drive for green energy dictates that the pits would anyway be in decline by now; and in some ways, the question posed by this collection is how deeply we should mourn them. No. The real heartbreak – and the thing that despite everything, binds Burn decisively to her place of birth – is the way it was done: brutally, vindictively, and with no plan for how communities that were almost entirely dependent on coaling would survive without it.

It’s the repercussions of this overnight “consigning/of usefulness to nothing” that form the heart of the book. Dust is the metaphor here: “There was only dust left” concludes Burn, surveying the wreckage. Still asking too many questions, she gets a dead-end job in a supermarket where “Vodka/is always on offer” and customers form a “line of people waiting to share their sadness”. Xenophobic political parties and ideologies like Brexit gain traction. In the stark ‘You Kipper’, Burn serves a sweet, grandfatherly man at the checkout and feels an urge “to snoodle him, tuck/ him up”, only to glimpse “His membership card for the Kippers/and I want to be sick”.

The pit village was an enclave of heavy industry in the midst of countryside – indeed, the passing of this unique relationship is perhaps one of the things Burn regrets most. Horses and farm work offer relief; and the interplay of pit and nature permeates her poetry and adds to its atmosphere. The death of the village is likened to “watching/a great bird coming to rest, folding its wings/for the last time. Shedding feathers…becoming ash.” And while others compared Arthur Scargill’s idiosyncratic take on the comb-over to the processed breakfast cereal Shredded Wheat, Burn declares that it “rose from his head like a shredded bat.”

One of These Dead Places covers a long time-scale of forty-odd years, from the 1970s to the Trump presidency. Political poems add context, but the best of the collection is its witness to the impact on real lives of being tossed aside like so much dross by the faceless expediency of industrial restructuring. There is honesty here that the past didn’t work for everyone; but the stand-out message is that no one gains when human beings are treated without dignity.

One of These Dead Places is available online from Culture Matters. Jane’s next collection, Be Feared, is due out in November 2021 with Nine Arches Press.