REVIEW: HOLLY MAGILL’S ‘20’

By Stella Backhouse

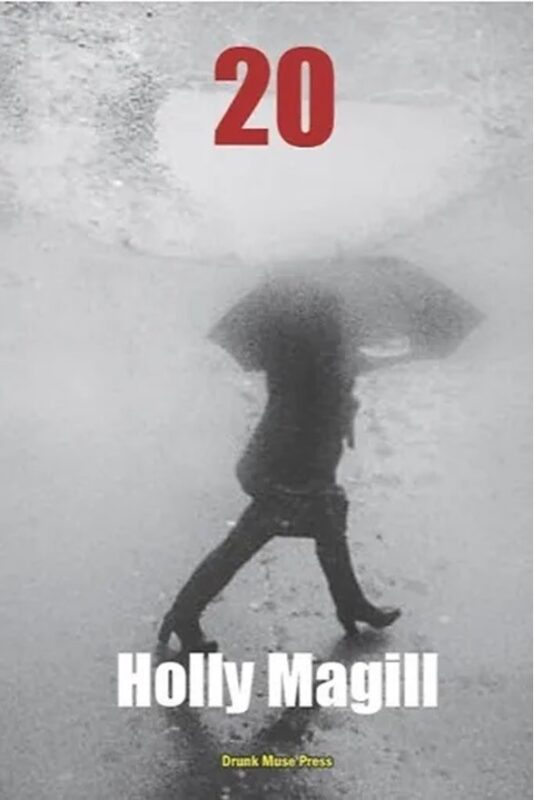

20 is quite possibly the shortest title of any collection I’ve reviewed. But even though it consists of just two little characters, the most important part of it is arguably neither of them: it’s the space in between. That’s because Holly Magill’s 2023 pamphlet is about transitions and different timescales – chronological, mental – that run parallel to each other but not always in sync. ‘20’ refers to Magill’s age in the late 1990s, when most of the poems are set. It’s the story of a world that’s turning from one millennium to another, from one technology to another; and of a young woman who’s turning – glitchingly, lurchingly – with it from child to adult.

Magill is pitch-pitch perfect on those clunky closing years of the last century, but deftly avoids easy nostalgia. Twenty-five fast-moving years later, rather than heart-warming, it just feels odd to hear a twenty year-old wax lyrical about “Radio Rentals on the High Street./TV and video in one unit,/paid off over 6 months./I join Blockbuster, my own laminated card”. The TV is stolen four months after acquisition, leaving Magill to pay “the last two instalments/for the TV’s ghost”.

The collection opens with Magill as an awkward newbie in the supposedly-adult office environment, not only relegated to the desk “nearest the toilets/the fax machine, the post trays,/the slow strobe of the photocopier” but also ostracised as a social misfit: “Head down, pretend/Bowling Friday night – don’t tell Holly/is never heard”. She consoles herself with cultural snobbery, correcting other people’s scabby spelling and provocatively Irvine Welsh’s headline-making novel Trainspotting. Later, as she scrubs the tiny flat that is her first home of her own, “Paranoid Android wails greyly on Radio 1”. Prophesies of future catastrophe become the lens through which present struggles will later be recalled.

Eventually, she makes friends with a colleague called Tracey, but childhood patterns are hard to shake off. When Tracey invites Holly home after work, the evening goes more like an updated version of nursery tea: mini-pizzas served by mum (whose Christian name Holly can’t bring herself to use), glasses of shandy, teenage television in the living room and Tracey’s little sister embarrassingly convulsed by playground insults.

The problem is, perpetual childhood is seen as desirable in some quarters. Both Tracey and another colleague, Jane, acquire male partners whose preference is for women who are physically small. In Jane’s case, this is coupled with a sinister desire for her to play the little girl: her punishing exercise régime, penitential diet and smug declaration that “Have to buy children’s clothes. I’m so petite” don’t seem quite so annoying-but-harmless in the context of a husband who “claims her arm and they glide to the carpark./Strapped into his Mazda, her knees judder,/heels scrabble the footwell carpet”. Tracey’s boyfriend meanwhile, to ensure that no one else will want her, bullies a free-spirited young woman into the identity of someone old before her time, a “miniscule, quivering thing dressed like his mum”. With men in control of female identity, it’s not surprising Holly struggles to find an authentic template for adulthood.

Seen simultaneously from a past where the events they describe haven’t yet happened, and the present those same events have helped to shape, the concluding poems reprise the idea of telescoping time into a slippery mental landscape where anything is possible. ‘things I will experience in 5 years time’ documents a suicide attempt, but the more hopeful ‘I have no clue you exist’ builds on the idea of knowing/not knowing to explore the tantalising possibility that we may already have unknowingly interacted with someone who will later become important to us.

The final poem reflects on how social media has come to define us in ways that could not have been foreseen even as recently as the 1990s. Remembering herself as a lonely young adult, Magill seems thankful that social media was one pressure she didn’t have – at least at the time. Unfortunately “No one predicts/#ThrowbackThursday/#MeAt20/”: her lack of past documentation now haunts her present. Merging past, present and future in a single line, Magill declares that she has become “my own ghost in reverse”. But maybe it won’t always be this way. Like the stolen analogue technology that became the ghost of itself in an earlier poem – this too shall pass.

20 is available to purchase online, direct from publisher Drunk Muse Press, as well as other bookshops and retailers.