REVIEW: CASEY BAILEY’S ‘PLEASE DO NOT TOUCH’

By Stella Backhouse

Controversy over the BBC’s not-noticeably-overdue new take on Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations has reignited debate about the propriety of casting non-white actors in adaptations of British classics. For me, addressing these concerns through the lens of historical accuracy alone – arguing, that is, that the inclusion of black actors is a correction of white denial around how many non-white people were actually living in Britain in the period depicted by Dickens – misses the larger point. Which is that much of Britain’s nineteenth-century wealth and prestige was built on the back of enslaved African labour or on the colonial ransacking of the riches and resources of regions whose populations were not white. In that sense, whether they were physically present or not, people of colour were everywhere in nineteenth-century Britain. If they were not acknowledged, it was the result not of fact, but of choice.

In his 2021 collection Please Do Not Touch, Casey Bailey explores how it feels for a Briton of Afro-Caribbean heritage to be present in some of the most ostentatious legacies of Britain’s slaving and colonial past. Yet in the sumptuous stately homes whose construction was funded by the unapologetic exploitation of non-white people, Bailey finds this reality too-often concealed beneath reticence and denial that continues to this day. These feelings are elegantly exemplified in the poem ‘Trompe l’oeil’ – roughly translatable as ‘sleight of hand’ – about a painting that includes a black boy clad in a metal collar but described on accompanying information boards as a ‘page boy’. What angers Bailey most, I think, is the expectation that, in accepting this designation at face value, visitors will willingly collude in the bland fiction that “here, in this corridor/between actuality and invention -/the Black boy/in the collar is/a page boy”.

Anger about the real impacts of this endless re-writing of history is also starkly evident in the twin poems ‘Same’ and ‘Energy’. Facing each other across the page these poems contrast the lauding as “Voyager, captain, explorer, hero” of colonial freeloader Admiral George Anson, with the condemning as “Hooligan, crook, thug, criminal, villain” of the stereotypical twenty-first century Black gangster. Bailey certainly isn’t condoning gangster culture. But his point is that the celebrated Anson is just as big a thief. The only difference lies in perception.

Poems about the long shadow of history connect to poems about Black British reality through the continuing dispensability of black lives. There are a number of poems about violent death and the grief that follows it because loss of peers is such a heartbreakingly common experience among young Black Britons. In this context, the most shocking inherited trauma poem is perhaps ‘No Rod Spared’ in which a father metes out corporal punishment to his son “only to keep him/from drowning at the hands of another”. Elsewhere, however, the collection is unafraid to critique aspects of Black identity: the burial setting of ‘When The Roll Is Called Up Yonder’ compares the sincere Christianity of Afro-Caribbean elders with anger at “the boys who/took today for a fashion parade and stand far back on the path/now, terrified of mud on their Pradas”.

Hope and pessimism vie to be the take-away from this collection. Bailey has said that over time, he began to allow himself to enjoy the beauty of local stately homes even as their history remained present in his mind. This permission to self to relax is evident in lines like “It’s OK to appreciate the view/and still see the trauma, you know” from ‘If I Speak’. On the other hand, even without lines such as “Worn and wearied is a way of existence/round here” and “Optimism died with my friends”, the fifteen sonnets (the fifteenth is composed of the first lines of the other fourteen) that comprise the final cycle ‘Tomorrow, Yesterday, Today’ would by their very form and title convey a sense of being trapped and an inability to move on.

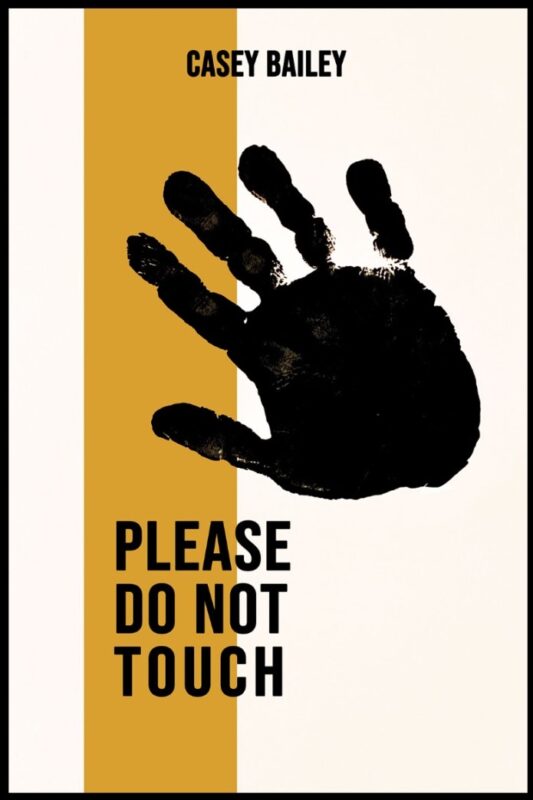

Perhaps the best parting thought comes when you close the book and look again at the cover: the handprint of Bailey’s young son and the words Please Do Not Touch. Because we need to touch. We need to open and to acknowledge so that today’s children can enjoy a better future.

Please Do Not Touch is available to purchase online, direct from publisher Burning Eye Books, as well as other bookshops and retailers.

plea