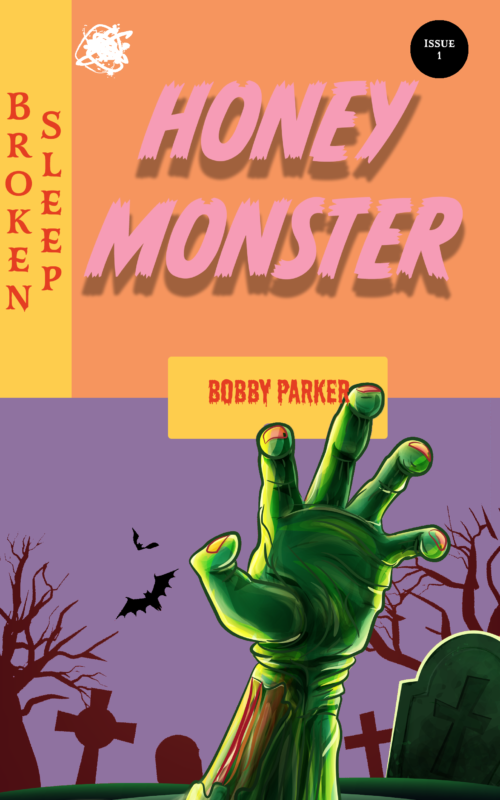

REVIEW: BOBBY PARKER’S ‘HONEY MONSTER’

Reviewed by: Stella Backhouse

It makes me feel old, this writing poetry reviews. Collections produced by poets much younger than I am are often loaded with allusions that go right over my head. Caleb Parkin’s This Fruiting Body is a good example. When I heard Caleb actually performing his work, I was aghast at how much I had missed in my review because my knowledge of gay club culture is embarrassingly nonexistent. Sometimes age works in my favour, though. 1970s TV adverts, you say? Ah! Now you’re talking my language.

Like the earlier Working Class Voodoo, Bobby Parker’s 2022 collection Honey Monster documents his working-class background and the bleak discourse of poverty, addiction, casual violence, mental illness and sexual abuse that formed the cruel narratives of both his child and adult lives. The contents matter-of-factly recount tragi-comic realities that should not seem normal, such as moving the gun on the kitchen table to “make room for butter and toast”. The style – rambling but controlled, hovering between poetry and prose – suggests someone who is using but still trying to keep it together; the claustrophobic single-neighbourhood canvas, someone who is too focused on the daily struggle to be bothered with the bigger picture. I had thought that the earlier collection’s exploration of gender dysphoria as explanation for some of Parker’s unease was less prominent here. But then my lived experience of ’70s telly kicked in.

The Honey Monster hadn’t crossed my mind in decades. So as part of my research for this review, I decided to reacquaint myself (what you can find on YouTube!) with the breakfast cereal adverts he starred in. By today’s standards, the ones from the 1970s are – depending on your viewpoint – either mildly disturbing or unsung icons of gender neutrality. In them, a male actor (not in drag) called Henry McGee, at the time best-known for his role as straight man to the then-popular, now facepalm-obligatory comedian Benny Hill, plays the Honey Monster’s ‘mummy’. It was my ability to identify Henry McGee that enabled me to unlock Parker’s extended title poem, which centres on his desire to kill a sadistic plasterer also called Henry. I haven’t completely worked it out – but I think it’s a retelling of the Oedipus myth.

Yes, I know Oedipus killed his father, not his mother; as I said – apart from an intuition that Parker is talking about growing up in the wrong family/body/house – I haven’t completely worked it out. But there are signs that he is leading us to Oedipus: Henry’s taunting pranks/riddles such as sending Parker for a ‘long weight/wait’ (The Sphinx); Henry’s suicide by hanging (Jocasta); his loser daughter (Antigone, meaning ‘worthy of one’s parents’); the whole-collection uncertainty about Parker’s family – is Resurrection Mary his grandma? Is someone else his grandma? Was Micky his father’s brother? Or just his friend? And then there’s the nickname Henry bestows on Parker: ‘No-Balls Bobby’ – recalling Freud’s Oedipus (castration) complex. The derelict house they are endlessly trying to renovate perhaps symbolises Parker himself. “If this is the wrong body…I’ll fucking ruin it” he says in the final poem. The house metaphor also recasts recurring images of haunted buildings and dismembered dolls as a mind whose other selves lie waiting in the shadows.

The collection is rich in arresting imagery. When Parker’s grandmother dies, his father “Sobb[ed] like a janitor’s mop”; decaffeinated coffee “tastes like an empty hotel room”. It is often blackly funny. But beyond that, and while this remains a collection about confusion, it is also a far more complex, far more controlled work than its depiction of disjointed events and random realities obviously accessed via drugs make it at first sight appear. It’s also about poetry: the Honey Monster.

Parker finds sweet release in writing, but exposing his dysfunctional family in poetry also risks exposing him to “the harm my words have done to others”. He wonders if he “was the monster or the victim” and fears he is “not sure what I’ll be like when the bus finally burns out. Maybe I won’t be like a monster anymore. I’m not sure if the fire is healing the bus or if the bus is healing the fire”. He has said he wants to move on from writing about his childhood. Watch this space.

Honey Monster is available online, as a physical copy or in e-book form direct from publisher Broken Sleep Books, as well as other bookshops and retailers.