REVIEW: BOBBY PARKER’S

‘WORKING CLASS VOODOO’

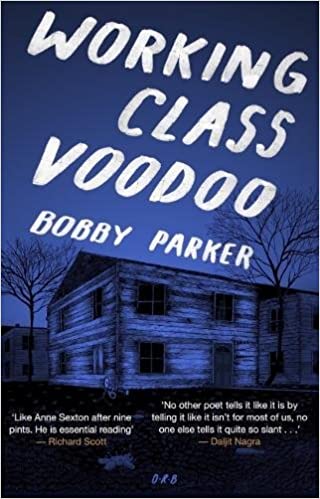

WORKING CLASS VOODOO BY BOBBY PARKER

OFFORD ROAD BOOKS

ISBN: 978-1999930417

£10.00/64 pages

Reviewed by Stella Backhouse

At the heart of Bobby Parker’s Working Class Voodoo is the affecting story of a sensitive man who, in large part because of abuses perpetrated by others against his body and against his will, struggles to fit into the world in which he finds himself. And yet despite the disorientation, hurt and humiliation inherent in his situation, beauty and love still remain the qualities he prizes most.

Parker’s dislocation manifests itself in a number of ways. He is at odds with the narratives of the white, working-class culture in which he grew up. He rejects the disguised racism of the taxi driver who drives him home. He rejects rigid dividing lines between male and female. And to the disappointment of his mother, dressed in her factory uniform with “no time for mental illness”, he rejects the sanctity of work – while at the same time admitting that “without [my mother] my daughter wouldn’t have nice clothes”.

But darker forces are also at work. Casually buried within the fragmented, undifferentiated terminal moraine of ‘Binge-watching Bad Memories’, we discover the genesis of Parker’s pain: “I don’t remember what he did/only that I was sweaty/from screaming for mum and dad/to come home/pay him for babysitting/get rid of him”. Reflecting the poem’s title and its pious overtones of culpable lack of self-control, Parker sums up the evening’s sombre legacy: “the victim heat/of guilt and shame was endless”.

But while addiction, self-harm, mental health problems and gender dysphoria frame the collection and shape its body, their worst effects are tempered by co-existence with unconditional love and unexpected beauty in a matrix so complex it defies explanation even by Parker himself. In the opening poem, after compulsively feeding his entire sickness benefit into a fruit machine in Spoon’s, he sits howling in his girlfriend’s car while she reminds him, over and over, that she loves him whatever. “No one said/this/was going/to be beautiful” he reflects. “[B]ut for some reason, it is.”

Love cannot not be questioned – only wonderingly accepted whenever it is offered. In ‘Rocket’, the last poem of the collection, Parker tells over some of the many troubling experiences of his life – sexual exploitation, self-loathing, identity crises – and confesses to his girlfriend that “it never occurred to me that I might be beautiful”. But later he reassures her that “When you tell me I’m beautiful I promise/to try/to believe you.”

Parker is also a father; and his tender relationship with his beloved daughter Isobelle is a source of hope and a possible route to redemption. His attempts to re-write his ruined childhood by inhabiting her space don’t work (“I…sleep in her empty pink bed/and I still dream/that I’m…atop at 20-foot wooden pole/that’s been shoved up my ass”) but seeing her at the playground, disappearing “into the silver tunnel/of the big slide, using my sleeve/to wipe away the mud and rain/before she comes out the other side” seems to offer the possibility of rebirth and renewal.

Parker’s ordeals at the hands of his abusers left him feeling that “intimacy/often feels/as if it belongs to them/and we can only borrow it/when we’re drunk/out of our minds”. But triumph does not belong to them – and that’s why the only area where I take issue with Working Class Voodoo is its title.

This painful tale of how an ordinary bloke slowly and haltingly overcomes terrible odds to rebuild his life into something meaningful lifts Parker’s collection beyond the limitations of class politics to the realms of the universal – a re-working for our times of St Paul’s words from another millennium: “Love…bears all things, believes all things, hopes all things, endures all things. Love never fails”.

Working Class Voodoo is available from Offord Road Books, Waterstones and other online retailers.