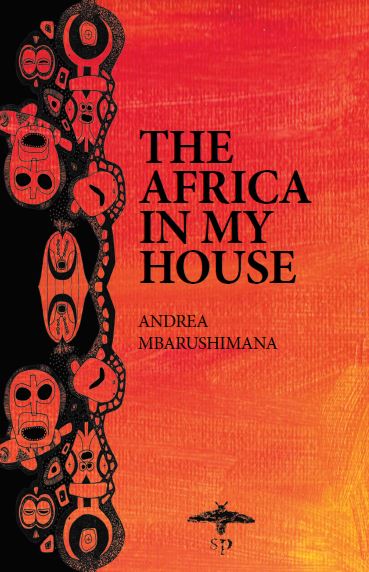

THE AFRICA IN MY HOUSE BY ANDREA MBARUSHIMANA

Silhouette Press

ISBN: 978-0993431524

£6.00/53 pages

A few lines into ‘Hyena’, the opening narrative of Andrea Mbarushimana’s short prose and poetry collection The Africa in my House, the unnamed narrator casually observes that “the buses are not as full as they used to be”. Coming from a book inspired mainly by the author’s experiences in post-genocide Rwanda, the inference is starkly clear.

Arriving in Rwanda in 1999, a mere five years after the end of the genocide, the white British Mbarushimana is confronted by a society that appears to be still in shock. Days are filled with “sitting around having awkward conversations on dusty streets”; men are “helpless”: they “stutter over speeches” and are “reduced to sipping their longing through warm beer”.

But what permeates this collection most of all is absence. From the dumb horror of a genocide site to the tipsy stagger home from a bar in a remote village, it is ghosts, vacuum, silence, darkness and emptiness that are at the collection’s heart – an impression eerily reinforced by Mbarushimana’s X-ray-like black-and-white lino-cuts of people and things irradiated from history.

It is not, however, a story without hope. For one thing, unlike their chronically-despondent male counterparts, the women have retained their spirit. They are all “big: big jokes, big hearts, big partiers, big movers”. Indomitable all-woman bar-owner Luce is “regal and rotund in her mobile-phone-print wrap” while a recent widow warns her chastened menfolk that “you will not have these children for your conflicts. They are MINE!” For another, Mbarushimana falls in love with a Rwandan teacher. They marry.

The marriage, subsequent move to England and arrival of Mbarushimana’s mixed-race daughter are the starting point of the book’s secondary themes of racism and post-colonial hangover. For her own part, Mbarushimana is clear-sighted enough to recognise that there is prejudice on both sides. When she arrives in Rwanda, she feels hated as an assumed “porn-star/lottery-win-white girl”.

But while the Rwandans overcome their initial suspicions to celebrate Mbarushimana’s marriage whole-heartedly, back in Britain people are not so generous. Being the mother of a mixed-race baby marks her out as “trashy/easy/benefits-class-white-girl” and even liberal friends view her photos of Rwandan children, whose vivacity she had known and loved, as stereotypical African “poor kids”. It was “as though you’d taken out my eyes, replacing them with TV screens” she says.

And along with the joy of the marriage, by the end of the book there are signs that Rwanda also is gradually starting to move forwards. ‘Inka’ (‘Cows’), the collection’s concluding narrative, seems to be told by the same person who told ‘Hyena’; the two act as companion pieces.

The story-teller is now revealed as a Rwandan refugee surviving in the Congo. He wants to give his companion a cow as a token of friendship, but because he has no cow, he gives a book instead. This simple gift sets off a chain of events that eventually leads to the road home, safety and a new start. Out of absence, out of not having, has finally come something positive.

Photography credit: Alan van Wijgerden, Fire & Dust 2018

Editor’s note: The Africa in My House is available online from Silhouette Press.