Conflict, Time, Photography

@ The Tate Modern,

26 November 2014 – 15 March 2015

www.tate.org.uk

War photography is the genre that crosses a tricky divide between reportage and art. It invites us to bear witness to (in)famous events, obscene acts that veer between the great and the intimate in scale. The most famous examples, like the children running form napalm fallout in Vietnam, have since become iconic scenes representing conflict generally, are then aped and re-imagined for new purposes, ultimately feeding into what Will Self recently branded the “pornography of violence” of which we have become the oversaturated and complacent consumers, constantly swiping or scrolling on to the next event that catches our diminishing attention span, for which, the internet seems able to provide an endless supply.

Tate Modern

I have issues with the term “conflict”, it can evoke ideas of mere argument, a clash of armed forces, and is also taken here to encompass wholesale exploitation of ethnic groups or their genocide. Faced with the crushing banality of fast-food modern media, scale seems determined to rule over questions of distance, on your doorstep, or very far away, perhaps this is understandable, though continually unsettling.

CTP takes an interesting angle to jolt us from the perennial problem of suffering mass death of affect. Much of its imagery makes use of absence, not shock tactics, allowing the facts and stories behind the image to fill in the gaps. People are often missing from the shots, apart from the sometimes bodies. This left me, the spectator, initially confused as I searched for a fixed point to anchor myself to in a sea of clouded landscapes, abandoned war machinery and faceless buildings; the explanatory notes, which are vast, highlight these spaces as post-firefight, elephantine graveyards of broken artillery and incongruous torture sites, that soon unravel into a dizzying span of human cruelty (man’s inhumanity to man etc.). The exhibition demands at least two hours to explore, and read, in full and I was thrown by the egotistical state of mind I felt where barren spaces seem to lose all certainty without a human in the frame to secure a narrative.

CTP takes a page (sorry) from Kurt Vonnegut’s most famous novel, Slaughterhouse Five: The Children’s Crusade (few people seem aware of the subtitle, but the book’s intro makes it pertinent – read). It presents us with a range of “in-action” conflict photography and more arty photography projects looking back over more than 150 years, that gather the fragments and try to present something meaningful in the aftermath. Sets of images skip chronological ordering from room to room, and, as in Vonnegut’s novel, are shown “unstuck from time” hopping across timezones and innovative methods of presentation, such as a visual record of family bloodlines, and the murderers who executed the last in line, contrasted by those that got away, often emigrating to start new lives abroad.

This might seem a rather breezy and lightweight approach to such a heavy theme, but it serves to underline the breadth of and depth of modern conflict, particularly throughout the second half of the 20th century, and into the 21st, as peacekeeping became the new priority and fresh conflicts were entered into under its auspices.

Belfast Telegraph

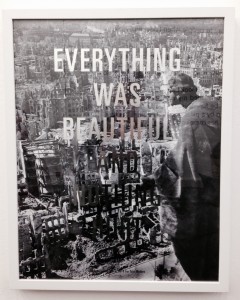

The exhibition is necessarily voyeuristic, but no more so than anything you might see in mainstream news coverage, which plays-out Baudrillard’s idea that we might as well be living through mere simulation. The CTP “cover art”, looking down upon the bombed-out shell of Dresden seven months after the allied bombing in World War II, is taken beside a statue at the top of its cathedral, belies the creative aspect of much of the work therein. The normal is rendered strange and unreal, cities are reduced to deserts; a series of egg-boxes with the lids ripped-off and even real deserts become moonscapes. For me this underlines the sense of war as an abstraction upon life, with conflict as its sometimes regrettable defender.

Luc Delahaye

The key thing I took away from CTP is a question of responsibility, of the author capturing artful chaos while all the time framing history; and for the idle viewer, who is, to be honest, often powerless to change and far removed from the acts portrayed. The simple conclusion, I would say challenge, presented by Vonnegut: “Everything was beautiful and nothing hurt”, unbalances an equation with no clear answer but nonetheless demands a response to aspire, not dwell in resignation. CTP continues its cue from Vonnegut’s mission to use his wartime experiences to create art, Slaughterhouse…, and to try and make sense of the posthumous event, after the dust has settled and hindsight allows reflection to take over.

A recent review of a recovered holocaust documentary warns potential viewers that the disturbing images it presents “cannot be unseen”, this hits at the heart of conflict photography as visual testimony, even though it may be after the fact. A gallery exhibition far removed from the scene still carries the power of record and the possibility to protest, marking the obligation of the living to bear witness to the dead.