Letters to Mary

14.03.2020

A Review by Sofia Furtado

Large format photos

In the evening of November 14, 1940, Coventry was the victim of one of the worst bombings in the history of World War II. Its impressive recovery story has made it UK’s official City of Peace and Reconciliation; yet, although 80 years have passed since the catastrophe of Coventry’s Blitz, and only the standing ruins of the Cathedral remain today to remind us of the brutalities of war, there is something of the intemporal in The Herbert Gallery’s last temporary exhibition “Quinn” (artist: Lotte Davies).

Portraying the fictional story of William Henry Quinn, it follows the protagonist’s trip from the south west of England to the north of Scotland. Travelling is presented as a response to harsh life changes imposed on individuals after the Second World War by generational conflict and global socio-economic collapse. The work symbolises the “real-world experiences of young men and women post-trauma in the early 20th century and now”. To William, it is particularly a journey of search for meaning and possibility of redemption through a path of loss, sadness and grief.

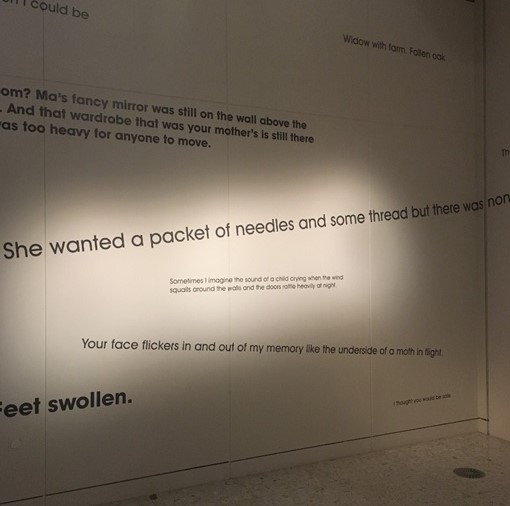

Quotes on the walls highlight fragments of Quinn’s notebook

The visitor is presented with a multidimensional and sensorial experience, afforded by an extensive and dynamic visual support. Large-format video and photography depict the stillness and constancy afforded by the British natural landscape of the 1940s. Nature works here as a symbol of renewal, vitality and new possibilities, contrasting with the chaotic environment of the urbanisation and, by parallelism, William’s emotional state. The sound of sea waves, the wind and the rustle of leaves complement the sense of melancholy the atmosphere evokes.

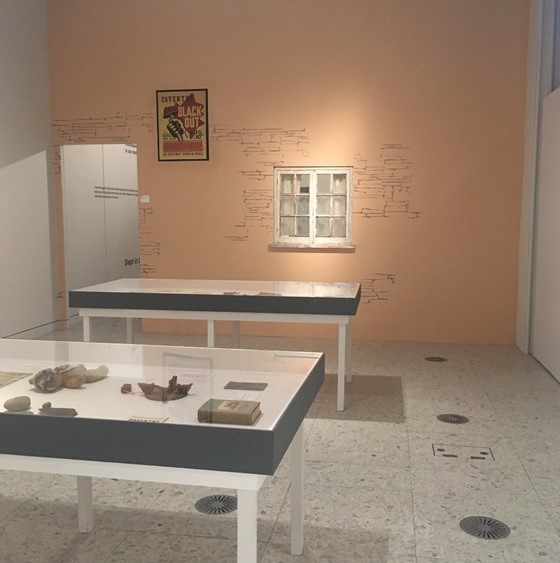

In the interactive area, a range of booklets, maps, wooden toys and postcards remind us of the evocative power of objects, not merely linked to their practical usefulness, but to their role as symbols, reminders, encapsulating precious memories and the stories of a past that, after all, is ours as well. The immersive experience is continued by a replica of the protagonist’s bedroom.

An oak dresser and a mirror sit next to a single bed with white sheets and a dark wooden frame. Along with them, a modest stand, a case, and a brown beret resting on the back of a farmhouse chair, occupy one corner of the room. On the bedside table, a small notebook is the key elemental-portal to Quinn’s emotional universe.

Quinn’s bedroom

The contents of the notebook consists of a repertory of letters destined to his wife Mary. In them, he narrates casual events of his day-to-day life, as well as his recurrent meditations. A nostalgic, almost dream-like tone dominates his reflections, whose articulation sometimes assumes the form of a single, seemingly indecipherable metaphorical quote. “Your face flickers in and out of my memory like the underside of a moth in flight” is scribbled in one of the pages. Many lyric traditions have used the moth symbolism to represent escaping or hiding from oneself, and the necessity of (re)connecting with our emotions. In Quinn’s descriptions, the anguish and grief are not raw but softened by the poetic imagery employed. However, the sense of emotional numbness that seems to (partially) conceal the protagonist’s complicated and unresolved feelings is precisely what gives them away.

Interactive area

Eugenides and Toibin, both novelists, have defended the “essential impulse in working” to be “to re-haunt your own house, or to allow what haunts you to have a voice, to chart what is deeply private and etched on the soul and find form and structure for it.” Quinn seeks isolation and peace in a lonely town of Scotland, resourcing to writing as a means to cope with the horrors of war and the loss (temporary or definite) of his wife. In writing, he does not simply find a means of catharsis, he tells a story; but the letters are never sent, so there is no one to read it; except for us, the clandestine visitor, and Quinn himself.

Perhaps Quinn’s writings symbolise more than the sorrows of a tormented soldier, resurrected by the artifices of an artist to haunt our contemporary indifference. Instead, they might be an attempt to fulfil our very human need for a narrative; a search for a glimpse of hope, if you want; and a reminder of the alikeness between humans, especially in hardship and pain. As Francis Ranford, Cultural and Creative Director of Culture Coventry has described it, “[t]his is a brave, bold exhibition which explores issues around mental health and loneliness that are as pertinent today as they were in the immediate aftermath of the war.”

Resources

“Quinn” webpage at The Herbert

If you missed out on the physical exhibition, The Herbert has a digital version for you to check out!

List of articles on war trauma

Expressive writing and coping with trauma

Some context re: Coventry’s Blitz