Ira Levin and the Green Issue

By Eve Volungeviciute

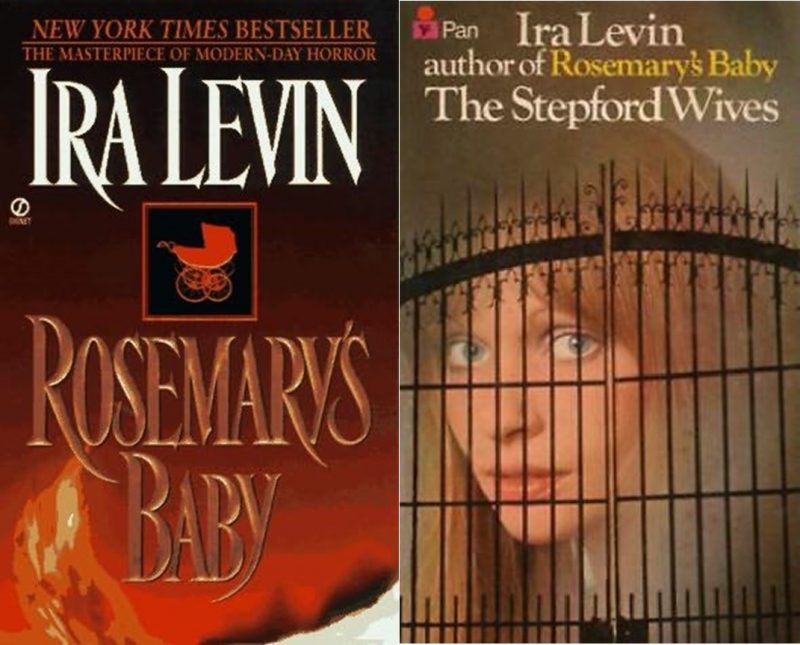

These classics have been widely discussed since they were first released; many interpretations and essay questions proposed, multiple adaptations made (some worse than others). There’s probably little new to say when it comes to Ira Levin’s Rosemary’s Baby and The Stepford Wives, but with The Green Issue coming out (and website picks already posted for people’s interest), I thought there was some food for thought in regards to the green theme when it came to the two novels. Granted, I am no scholar, but that’s the beauty of creative arts – they’re all open to interpretation, so I will try my best to make sense. Let’s begin!

The green theme of this issue of Here Comes Everyone magazine can be understood in a lot of ways. One of the more obvious ones are nature and climate change, but it can also be any items associated with the colour, as well as anything that represents it. Nature itself has been associated with femininity and reproduction, as that is the biological ‘purpose’ of women (this is a debate in itself), and all that resides within nature also goes through life cycles (which us humans are also a part of). Both Rosemary’s Baby and The Stepford Wives delve in the concept of the perfect woman and her purpose in the society, albeit they choose to explore it in quite disturbing ways.

Let’s start off with Rosemary’s Baby. Assuming those reading it already know the plot, I won’t say spoiler alert, but to summarise, it’s a story of a husband selling his wife’s bodily autonomy to the devil in exchange for fame. There aren’t really any questions as to who the ‘bad guys’ are for the audience, especially once we see what Rosemary is put through throughout the course of the novel.

One of the main themes of the book is Rosemary’s perception: is she overreacting as everyone around is telling her, or is there really something wrong? As readers, we know that it’s the latter even before Rosemary falls pregnant (following an incident which is a very off-handed portrayal of marital violence, fully intended to disturb the readers I’m certain). Throughout the pregnancy itself, the life drains from Rosemary at a steady pace as she’s conditioned to believe the constant pain and discomfort is normal. Unsurprisingly, she’s told that by a group of men who act like they know all about how a woman’s body is meant to function. Amazing how that’s not an issue today, huh? Oh, wait. The one time she’s about to get any real guidance from her friends, it’s cut abruptly short by Guy, her ‘caring’ husband, who pushes Rosemary to rely on the definitely non-suspicious neighbours.

Looking at the narrative through the green theme lens, it can be debated that there is more to the story than Guy and people from the Satanist cult deluding Rosemary and taking away her agency and independence. It’s also about Rosemary being robbed of what was meant to be a heart-warming experience: becoming a mother and starting a family has been twisted into something traumatising, painful and, ultimately, meant to benefit other people rather than the mother herself.

What’s even more heart-breaking and unsettling is that in the last moments of the novel, Rosemary ends up caving to her maternal instincts and accepts her Antichrist offspring. This action is a grim note to end the story on, showcasing the protagonist’s failure to gain independence from the societal norms expected of her. Granted, Rosemary can’t really blamed for this; when your spouse is willing to sell you to Satan to get ahead in his career and its unborn baby is essentially feeding off of you, there’s only so much you can do. The supernatural aspect of the story aside, the implications are, unfortunately, quite realistic – back in the 60s, women had very limited control over their lives and not all of them were lucky enough to have husbands caring and understanding enough to have a healthy and happy marriage. It’s hard to know who you can be when you’re pushed into a life frame that seems like the only option to follow.

Ira Levin continues the trend of messed-up family dynamics in thriller satire The Stepford Wives. Again, I’ll assume the readers of this article already know the plot and jump straight into it. The story of The Stepford Wives is also quite straightforward, even so looking through a feminist point of view – a young woman named Joanna moves to the suburbs with her family and, soon enough, begins to suspect the other women of the town are somehow subjected by their husbands into being the perfect wives.

Just like Rosemary, Joanna is told by her spouse that ‘it’s all in her head’. However, this is where the differences arise, as Joanna takes none of it and goes out on her own investigation. Joanna herself is certainly meant to represent a feminist movement of the 1970s, having her own established career as a photographer, not afraid to take charge, and certain of her own judgement. This novel takes a similar approach to its predecessor in a sense that, while it’s obvious something sinister is going on, we almost don’t want to believe it as the prospect that the townswomen are being replaced by mindless submissive robots just seems too ridiculous. And yet, as we readers find out, that’s exactly the case, which is all types of disturbing and establishes a lot of unfortunate implications. A lot of us were probably asking ourselves a very unpleasant question – would our partners/husbands trade us for someone that has our face but is only there for their benefit? Let’s think not.

A considerable difference between the climaxes of Rosemary’s Baby and The Stepford Wives is that, while definitely coerced and manipulated, Rosemary herself accepts the role that’s imposed on her and embraces it. Joanna, however, refuses to conform and is quite literally eliminated because of it, being replaced by a shell that resembles her only by appearance. In a way, you could say she was ultimately punished for not wanting to perform a role expected of her and substituted for ‘someone’ who would.

At the end of the day, both novels dealt with problems that were apparent and relevant to the time they were released. Sadly, while we’re definitely in a better place in terms of women rights than fifty years ago, there is still a long way to go in order to defeat the double standards in our society (for both men and women, as well). After all, we all want to believe we have agency and autonomy over our lives and aren’t conditioned into fulfilling certain types of expectations set out by societal norms. While the characters of Ira Levin’s works discussed in this article don’t particularly have good endings, their stories are an important representation of how certain limitations put on women can be damaging to their wellbeing, even if it is the ‘natural’ order of things. Let’s hope a day comes when stories like these ones are purely works of fiction.