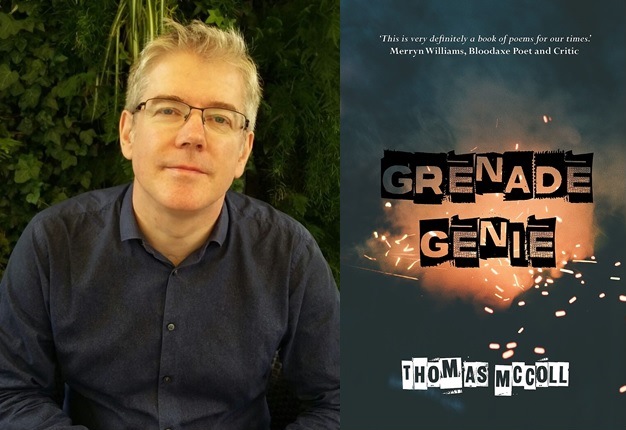

INTERVIEW: TOM MCCOLL AT FIRE & DUST

GRENADE GENIE BY THOMAS MCCOLL

Fly on the Wall Press

ISBN: 978-1-913211-13-4

£8.99/80 pages

“Trust me, somewhere, right at this very moment –

a moment borne out of desperation –

there’s another rat amongst the dinosaurs

about to pull out the pin with its teeth.”

-from ‘Grenade Genie’ (p.31)

London-based writer Thomas McColl has had poetry published in various anthologies and a vast array of magazines, including The Poetry Shed, Riggwelter, Atrium, Prole and Ink, Sweat and Tears. He has performed at events and festivals across London and beyond, has won and been shortlisted in a heap of competitions, and Thomas and his work have featured on BBC Radio Kent, East London Radio, and TV’s London Live. In 2016, he released his first poetry book Being With Me Will Help You Learn (Listen Softly London Press), and his second collection Grenade Genie was recently published by Fly on the Wall Press in April 2020. Thomas McColl also writes short stories and flash fiction.

On 4th June 2020, he was the special guest poet at Fire & Dust, our monthly open mic event. We’d been planning to have him headline at Fire & Dust for several years but did not manage to secure a date until 2020. Thanks to COVID-19, the gig took place online for the third time, via a Zoom video conference – which suggests Tom and host Raef might just be cursed to never meet in person!

HCE caught up with Tom after the gig, to ask him some questions…

In our 2018 interview, you reassured readers that you didn’t have a back catalogue for them to buy. But, tsk tsk, now you’ve published TWO books! Congratulations. How did the experience of putting together this second collection compare to your debut?

Thank you! And yes, I remember that was me reassuring people, who didn’t have that much time to read, that if they bought my one and only book and found they loved it, there at least wasn’t a backlist they’d then feel compelled to wade through. But, as you say – and as I’m very happy to confirm – I can’t claim any longer to have no backlist, as my second collection, Grenade Genie, was published in April and, yes, the experience of putting this collection together was markedly different to how it was for my debut. For one thing, my first collection, Being With Me Will Help You Learn, was quite eclectic, a kind of greatest hits of my best poems from the past 20 years, whereas Grenade Genie was compiled much more deliberately, with a definite structure and general theme, using poems I’d written recently that were much more political and outward-looking and socially conscious in tone.

The new book presents a clear shift from the first one, in that though there’s still a fair amount of that quirkiness and humour that there’s always been in my writing, Grenade Genie, as a collection overall, is much more serious, and even grim, in tone, and much more focused on presenting a clear theme, a theme that very quickly emerged, as I was writing these poems, of people being, or becoming, expendable in all kinds of ways. And while that’s something I’ve always thought was the case, one thing that became very clear to me as I wrote this collection is that while this knowledge can generate either a sense of hopelessness or the nothing-to-lose strength to rail against it, one strength of poetry is that even if only the former gets expressed, the latter is automatically achieved. And so I’m glad then I’ve managed – or feel I’ve managed, at least – to express this sense of expendability, especially as I really am feeling it more and more, the more I see and the older I get.

Who is your work aimed at – do you have an ideal audience in mind when you’re putting a poem together?

I don’t really think of any kind of audience when I’m putting a poem together. I always write for myself, in the sense that I’ll always ensure that I’m happy to put my name to whatever it is I’m writing. As to who then it’s going to appeal to, I won’t even try to second guess, as I’m often taken by surprise by who likes my work and which poems they like the best, and that’s one of the reasons why I write, to be surprised like that.

Having said all that, Grenade Genie is definitely a collection that’ll appeal to those who like poetry which has got something to say about the world we live in, as there are poems on subjects as diverse as Grenfell, workers’ rights, the NHS, social media, the refugee crisis, the environment, consumerism, the Iranian Revolution, William Burroughs and the cut-up technique and, last but not least, the onset of puberty and finding oneself attracted to the Religious Education teacher!

Your book is subtitled ‘25 brief studies of the cursed, coerced, combative and corrupted’ and divided into those four sections. Are you a fan of alliteration as a poetic device, or mainly just for titles?

I am, indeed, a fan of alliteration as a poetic device, and I very much enjoyed Ian’s use of it at the Fire & Dust gig. I do employ it in my writing (and not just with poetry but prose too) but, in terms of this book, you’re right, it does just seem to feature in its subtitle – and then in the title of one of the poems, the last one in the ‘Coerced’ section, Jan, Jen or Jean.

Alliteration, of course, can be overused; but, arguably, in this book, it’s been underused, and maybe in my next book, I’ll have to put that right by somehow finding that happy medium, though of course that’s easier said than done. I think what I’m trying to say is: I will will words to work that way, and without it worsening the work – or will I?

The narrators in some of your poems seem to feel social media has been/will be the downfall of human society. To what extent does this reflect your own feelings – are we as doomed as your four C-word sub-headings suggest?

It very much reflects my own feelings, though I also do accept how fantastic social media is, and how much it’s enabled me to keep my ear to the ground and get connected in terms of my writing. And that positive side of social media has, this year, been especially helpful, for even the four ominous C-words that sub-head my book – Cursed, Coerced, Combative and Corrupted – were all blown out of the water by the new C-word, Coronavirus, which really changed our lives adversely, and made social media even more important than it’s ever been. At any rate, without social media, I wouldn’t have been able to promote my book at all.

And that’s the irony, I guess: as soon as I released this book containing poems which rail, to some degree, against the fact that there really is this underlying sinister element to social media (in terms of privacy and people being controlled and directed without even realising), I’ve ended up having to employ and rely on social media more than ever before – and though that possibly makes me hypocritical, it also, to a large degree, just proves my point. We are pretty much all dependent now on social media in so many ways, and that’s the thing, when something’s that good and helpful, and has incredible benefits, you need to then be that more vigilant. I basically have mixed feelings about social media: it was, and is, revolutionary, and has opened up societies and helped to bring about massive cultural change, and I think my poems on the subject are mainly to prompt people, and prompt myself, to keep in mind that there are hidden forces at work as well, and that something for free is never really free.

You performed ‘The Greatest Poem’ at Fire & Dust, which touches on, in a somewhat critical way, the phenomenon of Instagram poetry. We’re interested in your opinion on this, if you’re willing to elaborate. Is there a concern that, if the works on social media attracting most attention are “trite”, this devalues poetry overall? And have you – so far – written any poems for Instagram yourself?

I’ve never written any poems especially for Instagram, but I did consider posting some of my shortest poems on my recently set up Instagram account, for while all 25 poems in Grenade Genie are far too long to be posted in full on such a platform, there were a few very short pieces in my first collection, Being With Me Will Help You Learn (including a 12-line poem on the subject of homelessness called The Chalk Fairy, which ended up being the most popular poem in the book and even got quoted in the London Evening Standard). But, while I think all my short poems would go down well enough with anyone who came across them, I don’t think any of them would stand a chance of going viral as none of them possess that irritating immediacy that any proper Instagram poem always possesses, just like fast food also always possesses. For, as far as I’m concerned, Instagram poetry is pretty much all just motivational mush that can surely only give at most an instant hit, a gratifying feeling that soon disappears – except that many people insist their favourite Instagram poems have really spoken to them in terms of things going on in their lives, and have helped them to cope, so what do I know?

And that’s the thing: I guess I simply have to accept that this style of poetry – as practiced by the likes of Rupi Kaur and Atticus – just isn’t for me and, to be fair, I don’t think the phenomenon devalues poetry overall (even if I don’t think it does anything for it either). The poet referenced at the beginning of The Greatest Poem – T.S. Eliot – remains, still, at the top of the canon, and even Insta-poetry’s most ardent supporters surely couldn’t deny that there’s a clear line of separation in terms of quality and depth.

But maybe I should simply speak for myself – and, thing is, maybe I’m simply jealous – though I also have to say that, even if I don’t like something, I always kind of admire someone who blazes a trail, and Rupi Kaur certainly did that. As to whether she and other Instagram poets will still be read in a hundred years’ time remains to be seen, but being as William McGonagall – the worst poet in the English language and someone who gets a mention in The Greatest Poem – is still being read well over a hundred years after his death, there’s still hope for all those Insta poets yet.

Grenade Genie offers up commentary on issues and situations in our world that tend to make people unhappy – yet there are plenty of funny/lighter moments. Was it difficult to get the balance right, between serious message and an entertaining comedic tone, or does that occur naturally when you write?

I’d have to say that I wasn’t particularly aware of trying to get the balance right, or thinking that’s something I’ve got to do – even though it really is something very important to consider when writing about serious subjects – so I guess it did occur naturally as I was writing. It has to be said that pretty much all of these poems went through extensive edits, sometimes over a period of years, and that was before the collection was even accepted, and then once it was accepted there were yet more edits as I worked through the poems with my publisher/editor, Isabelle Kenyon, to iron out any issues that remained. But yes, in order to sort out all kinds of issues – and definitely not least issues of tone and pace and getting the balance right – I think that really is so important to do, to go through that process of extensive editing, not just by myself, but with another person I can trust and respect and who, in having some distance from me, can be objective. That’s just one of various reasons why I’m glad my collection found a home where it did, with Fly on the Wall Press.

Have you participated in many other virtual events during the COVID-19 lockdown? How are you finding these gigs, compared to performing in person?

I’ve participated in a few. The first one I did was an hour-long set as part of ‘WinchesterFest – a Livestreamed Poetry Festival’, which was a great way to launch the book which had just come out, and then, in between doing that and being at Fire & Dust, I’ve done a few open mics, and have always enjoyed the events. By their very nature, they’ve tended to be slightly anarchic affairs, with people all in different locations, and everyone, including the organisers, trying to get to grips with the technology and this new way of doing things, and that definitely makes for an interesting night. And one novel thing about Zoom events is the Chat function where members of the audience can leave comments as the poet is reading. It was fantastic, at Fire & Dust, to read all the lovely comments people had made about me and my poetry.

So there really has been lots of positive aspects about these Zoom events, not least in keeping people connected in these very strange and difficult times, which has been so important and useful, but still, in terms of interaction and atmosphere, there is that slight disconnect which makes it impossible for a virtual gig to replicate the buzz and excitement of a live gig, and I can’t wait for things to get back to normal.

During the gig, you mentioned that you’ve worked remotely several times before. What advice would you give to writers who might need to work this way with an editor or a small press? For instance, did you have any experiences that helped improve how you communicate and negotiate ideas?

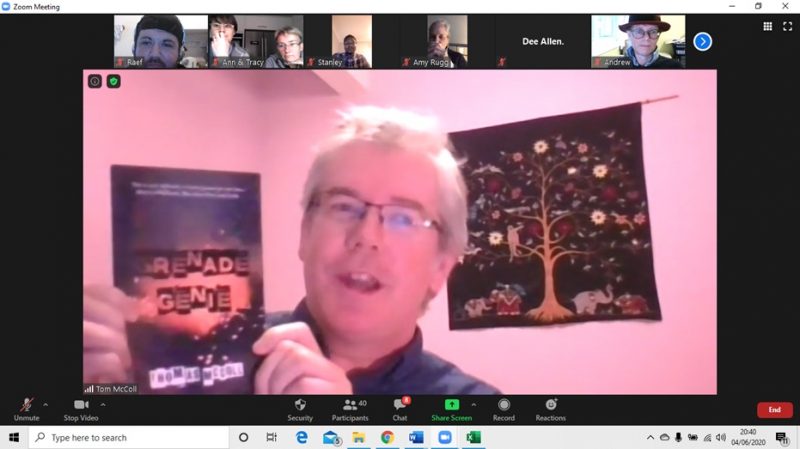

Yes, I was saying, during the gig – while holding up my book as proof of a great result – that it was amazing what can be achieved between two people without them having to actually meet in person.

Everything in terms of the book was sorted out with emails going back and forth between me and Isabelle, often with Word/pdf attachments containing edits, and jpegs/pdfs of proposed images/designs to use. The editing process was particularly useful in sorting out the middle section of the title poem, and with Isabelle’s prompts and suggestions I got there in the end, which was great as I’d been trying for years to solve it and make it flow much better, and I finally did, with Isabelle’s help.

Obviously, the two of us would have had to work remotely anyway under the current lockdown conditions, but it does seem to be the way things are done these days between authors and editors, especially if the author and Press are in different parts of the country (I’m in London, Fly on the Wall Press is in Manchester). In any event, before lockdown occurred, Isabelle and I had been due to meet for the first time in person at the Birmingham launch of the book, at Whisky & Words in the Jewellery Quarter on 20th May, but that of course got cancelled. So, the two of us being at the Fire & Dust gig, and being able to see each other reading live on the screen, is as near as it’s got to us meeting in person.

It’s not an easy question to ask or answer in these current times, but…what are your upcoming gigs/future projects?

I intend to promote this book well into next year – and, in view of the current crisis, I think that’ll be absolutely necessary. Before lockdown happened, I’d had my first ‘tour’ lined up, including the aforementioned headline slot at Whisky & Words in Birmingham, a book signing at the Book Corner bookshop as part of the Saltburn Folk Festival, and a one-hour performance slot at the Leamington Poetry Festival. These and other dates stretched from May through to August, and while it’s a shame that they couldn’t happen as originally planned, and everything’s still up in the air at the moment, I’m in for the long haul, as I’ve always been. I believe in this book, and I’m very lucky to have a publisher who believes in it too, and very grateful to Fire & Dust for offering to put me on. Much appreciated, cheers!

People can get in touch about gig bookings and keep updated about Tom’s work on:

Twitter Website Instagram

Grenade Genie is available for purchase from the Fly on the Wall Press website, in both paperback format and as an e-book. Tom’s first collection Being With Me Will Help You Learn is available online from Listen Softly.