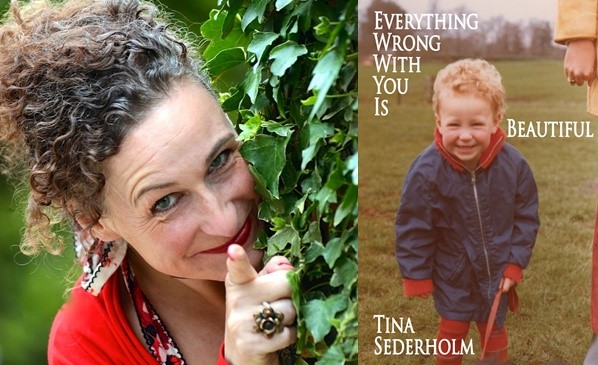

INTERVIEW: FIRE & DUST MEETS TINA SEDERHOLM

EVERYTHING WRONG WITH YOU IS BEAUTIFUL BY TINA SEDERHOLM

Burning Eye Press

ISBN: 978-1911570011

£11.99 (incl. shipping)/100 pages

“She will not be like other people. Ever.

She will be the kind of child

that you encourage to be herself,

then bitterly regret it

when she does just that.

[…]”

-From ‘Prediction’ (Everything Wrong With You is Beautiful, p.10)

Tina Sederholm is a poet and theatre-maker who has created and toured four one-woman shows, including six runs at the Edinburgh Fringe. Her writing contends with the idea of a “well-lived life”, exploring the gap between her ideals and the reality she finds herself in, whether that’s with relationships, art or herself. Tina has won more than 20 poetry slams and published six books, most recently her poetry collection Everything Wrong With You Is Beautiful. She is currently working on a new show: REST. Most of all, she wants to live in a world where people laugh with each other, not at each other.

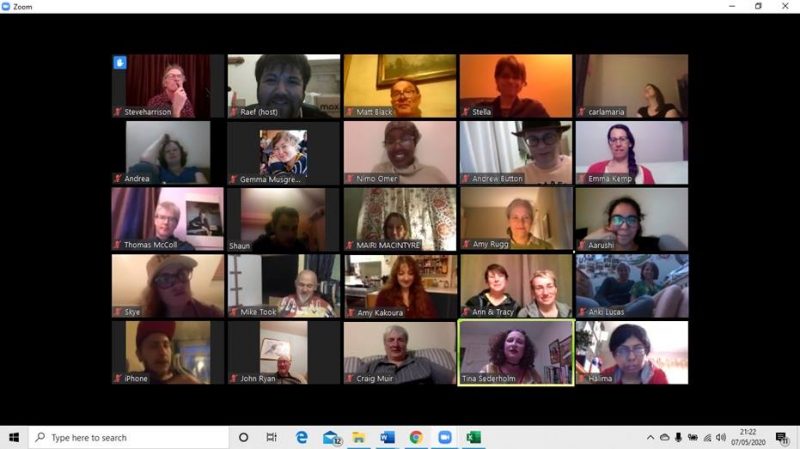

On 7th May, Tina was our second ever virtual headliner at Fire & Dust. The event was a busy one, full of friendly faces and a diverse range of poetry. One difference between a gig on Zoom and our usual gigs is that audience members are able to offer immediate feedback, using the chatroom function. It was clear from people’s comments that they found Tina’s set upbeat and inspiring.

HCE caught up with Tina after the gig, to ask her some questions…

When did you first know you were a poet, and was this as terrible a revelation as the doctor in your poem ‘Prediction’ declares?

I didn’t really know I was a poet until I was 35. I’d written a little at school – mostly bastardised Cure and Siouxsie and the Banshee lyrics – but once I got involved with my career as a three-day event rider and trainer, there was no space in my life for anything else. When that came to an end in my early thirties, I started writing short stories and films, but while I was in Australia, a friend gave me a tape of the poet David Whyte. I sat in a rubbish strewn park in a suburb of Sydney and listened to it with the tears pouring down my face. I only understood about 30% of what he was saying, but it moved me incomprehensibly. When I got back to the UK, I went to some poetry readings, and they did not do it for me in the same way. But when I saw a poetry slam, I thought Yes! I loved the performance aspect of it, and the high energy. I saw that I could be funny and profound at the same time. It was only a terrible revelation inasmuch as I had thought I wanted to be a novelist or scriptwriter, which seemed way cooler than poet. Also, these were things my parents could sort of understand. They definitely did not get what a poet was.

Who is your work aimed at – do you have an ideal audience in mind when you’re putting a poem together?

I am a completely selfish writer and certainly when it comes to early drafts, I write poems for myself. To work out what I think or feel about a subject, particularly what I would call ‘modern malaises’. But because I am trying to speak to my own insecurities, I think by default, I speak to others. When I perform early versions at open mics, I try to see how the audience react – did they get that bit the way I do, or am I being too oblique/up my own arse?

One of the sections in your book is titled ‘The Reluctant Feminist’. Would you describe yourself as a feminist poet (reluctantly, or otherwise)?

I only knew I was a feminist in 2012, when a journalist told me I had written a deeply feminist show (Evie and the Perfect Cupcake). Yes, I am a feminist but I don’t announce it because feminism is a large spectrum and like the word ‘God’ has a tremendous amount of baggage attached to it. Hence my reluctance to battle through all that rubbish. I like to feel I embody feminism, rather than shout about it. I am still amazed how many women aren’t feminists though. Why would you not want to stand up for yourself?

What, in your opinion, are the essential elements for a “good” poem?

One of my favourite quotes about writing poetry comes from David Whyte. He says that a good poem is about an experience, but a great poem IS an experience. I am not going to pretend I pull off the ‘experience’ that often, but it is what I’m aiming for. Things that help make a great poem are a cracking first line. Tangible juicy images. Good sounds. And space. What you don’t say is as important as what you do say. The gaps let the reader be part of the experience by giving space for their reaction. If you explain everything, you are doing a poem at them, not including them.

But you hardly ever achieve these things in a first draft. My first drafts are terrible. Sometimes I will have three runs at an image, all within one stanza. But I do this because I know I can edit later. I love the editing process. If you write a lot, you can take away a lot. I am a strict editor, and consistently re-work poems, even when I might have already performed them for months. This is where many less experienced poets fall down. They don’t edit enough, they keep lines for the sake of the rhyme or because they’ve fallen in love with them. But this is the stage in the process when the poem is no longer about you, but whether it serves the audience.

Is it hard work getting a poetry show ready for Edinburgh Fringe? What are the ups and downs of performing at a festival?

Yes. It’s one thing to get one poem polished. Then you learn to put three together for an 8-10 minute set. Then it’s 20 minutes. But to sustain the audience’s interest for 60 minutes – well, you better be writing about something interesting. Because I was involved with a sport at a high level, I am lucky to be used to putting in the hours and staying the course, often for years. When I am writing a show, I say to my husband ‘There’s no show. This is total crap.’ at least once a fortnight. He used to comfort me, but now just rolls his eyes and says ‘Oh. We’re at that stage of the process, are we?’

Having said that, I love it when a show comes together. The great thing is to gather support. I wrote my first show, because my friend Lucy Ayrton and I dared ourselves to each write one for the following Edinburgh, whilst we were on the train home from the Fringe in 2011. We would meet every week and read each other’s work and keep encouraging each other. We begged favours off friends to write little bits of music for us. My husband, who had made some student films, directed the show. We totally made it up as we were going along. But because I had a buddy, the show got made. I don’t know that it would have done otherwise.

Edinburgh itself is incredibly intense. You need to build resilience because you are going to be exhausted and pushed to your mental, emotional and physical limits. Having said that, it is also brilliant. Performing 22 shows of my own and then doing about another 30 cabarets, guest spots, etc. throughout the three weeks always improves my performance by a mile. You also learn to shrug off a bad performance, because there is always another one coming up.

Your new collection This Is Not Therapy is due out in 2021. What sort of themes can readers expect to encounter?

It may have another name by then! I’m notorious for changing the name of my projects several times. My over-riding obsession is how do I get to my end of my life and say ‘Yes, I made the most of that. I did all the things I wanted to.’ I am continually striving to find meaning in the life I’ve got and to expand it. But nothing gets in the way of that more than our own belief systems, inhibitions, anxieties and insecurities. So, I will be busting a few more of those open. In my first collection, I really wanted to look at the value of failing. Having been brought up with Olympic athletes training in my garden, I had a very low tolerance for failure. But after several experiences of life not going to plan, I began to see that, actually, my failures were what made me the person I am, not my successes. Ask anyone what were their five most influential life events, and most of them will be – death of a loved one, divorce, losing a job. Creating Everything Wrong with You Is Beautiful taught me to be more compassionate towards my shortcomings.

With that self- acceptance, I’m not so attached to results anymore and, as a result, I’m becoming more daring again. Alongside this, I finally realised that the Hero’s Journey – Joseph Campbell’s theory that the myth of being called to adventure, facing trials and tribulations and coming home is endemic to all cultures – is not actually about getting what you want. Sir Lancelot never finds the Holy Grail, Indiana Jones doesn’t get to keep the Ark of the Covenant, Frodo can’t keep the ring. It’s not about getting the prize. It’s about what you learn and, to me, more importantly, what you heal in order to become a whole person. So that’s what I’m exploring in the new book.

It’s a pretty amazing feat to have been a slam champion twenty times! Any top tips for open mic-ers planning to venture into the slam poetry scene?

I love slams. They are an excellent training ground for learning to read the audience fast, change the energy from the person who went before you (or ride the energy if they’ve given a stellar performance) and make an impression fast. Having said that, it can feel unkind when an audience doesn’t get your poem and you get a low mark. I’ve come both first and last in slams with exactly the same poem. So it does help you to develop a thick skin and deal with the fact that audiences are not always going to like you and that has little to do with who you are. It’s a whole raft of things.

My tips are: Be as grounded in your body as you can before you go on. Learn diaphragmatic breathing, so that when the nerves strike, you are able to bring yourself back quickly. When you get on stage, give your toes or hands a little wiggle, so you are there. Then enjoy the poem. Enjoy the words. Yes, it’s easier to win with a funny poem, but if you are not a funny writer, own the elegance, or lean into the poignancy of your poem. Audiences respond to authenticity. So don’t try to copy me or other slam champs (I made this mistake a lot when I started). Be you. If the audience sees you, they will forgive you tripping over a word. I have a little routine before I go on, which is go on, ground my feet, breathe and close my eyes for one second to feel the emotion of the first line. For my poem ‘Prediction – sorry you’ve given birth to a poet’, I always see myself in the hospital room, feeling that anticipation of a baby about to arrive. I’ve had a lot of practice so now I can do it in a nanosecond, and it always puts me in the right frame of mind to deliver that poem.

Do you engage with a lot of poetry yourself, and does this have any influence on your own work? Which collections/poets have recently made an impression on you?

Yes, I do. But I’m choosy about who I read. If it’s not moving my guts, I’m not interested. Many performance poets are better seen live than on the page. The clue is in the name, after all. But ones who do work on the page for me include John Osborne’s ‘No-one cares about your new thing’ and JonnyFluffypunk’s ‘Sustainable Nihilist’s Handbook.’ Page poets I return to over and over again are Mary Oliver, David Whyte (though listen to his poetry videos, because he is a page poet who also inhabits his poems in a spectacular way) and Billy Collins. Jo Bell and Robert Peake are poets I will always stop to listen to or read.

How was the experience of headlining Fire & Dust online? Obviously, we were sad not to be hosting you in person. But has it encouraged you to check out some other virtual poetry gigs during the quarantine?

I love to tap into the energy of the audience and take them on a bit of a ride, so while I am performing, there is a part of me also reading and feeling the room. That’s not possible on Zoom, so I was a touch nervous, performing my poems into a bit of a void. But it was better than I thought it would be, so I would be open to doing a few more. I have been to some other ones, but I find it hard on the eyes to spend too much time in front of a screen, so I tend to listen whilst I’m pottering around.

How are you coping with the lockdown? Some people seem to be writing more than usual, while others are creatively blocked by worries and loneliness.

I am so lucky because I live in a beautiful village, so I can still walk miles every day, which is very important for my mental health. After the initial shock and adjustment, I have actually been enjoying it. It’s been so good to do things at my own pace, my own schedule. I knew I had enough money to survive for three months, so I made a vow at the beginning to not let myself go into any spiral about finances. Again, having grown up with horses, I am used to training for a big competition for months, even years, only for the horse to injure itself, or a virus to go through the yard and the plan to be scuppered. So I’ve learnt patience early on. I didn’t write a lot at the beginning. I had flu, or possibly a mild version of Covid, and it knocked the crap out of me. But I feel like I’ve finally caught up on sleep and I have more energy for creating than I have had for years. So watch out!

We were impressed by how much you manage to smile and laugh while performing your poems! Are you a cheerful person anyway, or do you do this to help the crowd feel more positive?

I smile and laugh because I bloody love performing. It’s the time I feel most alive. I love meeting my poems like they are old friends and we are having a cracking get-together. I love the connection with other human beings and letting the audience know they are in safe hands: they can laugh and smile and respond. But if I’m not in a smiling mood, I don’t. Sometimes I am serious but it’s because that ’s what is bubbling up inside, not because I think I should. I used to think I should smile, whatever I was feeling, but people can spot that insincerity a mile off, and it is a huge turn-off for them, and makes me feel empty and fake.

It’s not an easy question to ask or answer in these current times, but…what are your upcoming gigs/future projects?

The problem with having all this time on my hands is I am coming up with far too many ideas! I was meant to premiere my new show, ‘REST’, this summer and I am still working on it. However, it looks unlikely that we will be back in theatres and live performance spaces for a good while yet. So, I am currently toying with doing an abridged version as a film shot in my house.

As for poetry gigs, I am happy to wait until we are back in performance spaces to perform again. The online gig is great for keeping in touch, but for me, live performance is where it’s at. I hope to do a book tour for This is Not Therapy in 2021, but I’m still waiting for confirmation of publication dates

Where can people follow your work or get in touch about gig bookings? Time to plug some links!

Yes! The best way to hear from me is to join my mailing list. I only send about one a month, but as well as what I’m up to, I like to include tips for creative inspiration and links to useful resources for poets and performers. You can sign up here.

I also blog about creative practices such as how to edit, how to shape a story or poem.

You can also follow me on:

Facebook Twitter Instagram

Everything Wrong with You is Beautiful is available for purchase from Tina’s website, as well as some of her other books.