INTERVIEW: FIRE & DUST MEETS STEPHEN LIGHTBOWN

Day 1: Bristol

I drink the juice from the tinned peaches.

Gulp down survivor syndrome, ignore

the urge to add cream and lady fingers.

Thinking of dessert doesn’t seem right

when I can’t smile at you across our table

raised on four yoga blocks. A small ooze

of sugar water escapes from the tin

and settles in my beard. I leave it, fantasise

about an exhausted bee replenishing

itself on my chin. I wipe the sticky residue

away with a grubby hand. I’m so bereft

of contact that the thought of a bee

coming for pleasure, then leaving

to return to the hive, revitalised,

is simply too much.

__________________– from The Last Custodian, pg. 15

Stephen Lightbown is a Blackburn-born, Bristol-based poet. Stephen writes extensively but not exclusively about life as a wheelchair user, having been paralysed by a sledging accident when he was sixteen. He has published two collections of poetry, both with Burning Eye Books. Only Air, his debut, came out in 2019 and his second book, The Last Custodian, was published at the end of June this year.

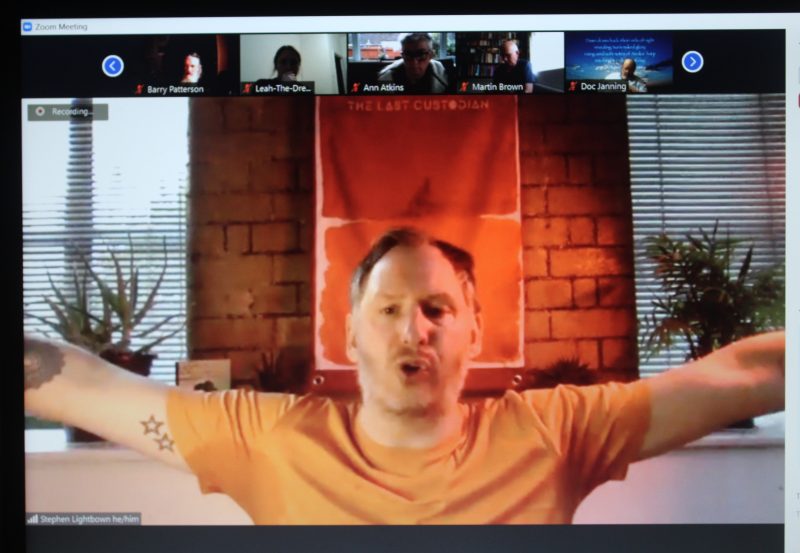

On 1st July 2021, the day after The Last Custodian was released, Stephen was the guest headliner at our Fire & Dust poetry night. His readings went down well with the audience, and we caught up with him after the gig to ask a few questions…

HCE: Tell us a little about your background and journey as a writer so far. What inspired you to start creating and performing poetry?

SL: I came to poetry fairly late, in my mid-30s. Until recently, my day job had been in PR and communications within the NHS. I’m fairly creative but had felt stifled at work and wanted an outlet. So, I bought a notebook and started to jot some ideas and scribbles down. This coincided with a marriage break-up, a family bereavement and wanting a distraction. I signed up for a poetry course with Malika Booker and that was my way into poetry. On the course we were tasked with writing a letter poem and I wrote one to my legs. I’d always thought I’d use the writing to talk about anything but my disability, but something happened when I wrote that poem. I shared it with the group on the course and Malika suggested there could be more poems to write about my disability. And she was right. I went home, started writing and I’m still going.

HCE: How did you find the experience of putting together your second collection, compared to creating Only Air?

SL: The two were really different. With the first collection I didn’t know what I was doing, the process of putting a collection together was new and thinking about ordering poems wasn’t something that came naturally. Also, that book was written over a few years and was incredibly personal as it captured my experiences as a wheelchair user over a 20-year period. I knew with the second collection I still wanted to write about disability, but maybe not my own experiences. So, The Last Custodian is a fictional account of a wheelchair user who survives an apocalypse. The idea for a dystopian collection came from a frustration of not seeing disabled protagonists front and centre in the sci-fi genre or, where there are, it not feeling authentic. I actually found the process with the new book really enjoyable. I just let my creative ideas flow and was able to build characters, a new world, and enjoyed the liberation of thinking what could this person do and where would they go.

HCE: Did the Covid-19 pandemic influence your choice to write about a post-apocalyptic world, or had you already started creating The Last Custodian before it kicked off?

SL: I started to write a few scratchy poems in late 2019 and then the pandemic hit and writing about an apocalypse felt quite easy. In the space of six months or so I had written more than a hundred poems and I was using what was happening in the real world as inspiration. The Last Custodian is not a pandemic collection as such, but it is definitely influenced by it. It was shielding that gave me the idea of thinking what would happen if something terrible happened and someone with a disability was able to thrive outdoors rather than being forced to stay inside. Once I had that idea, the structure came quite easily.

HCE: Is there a particular message you’re hoping that readers take away from the new book?

SL: I’m at peace with accepting that once you write a poem or a collection, ownership of the meaning moves from the poet to the reader, and I love to see what people take as the meaning to them. That being said, there are things I address in the book: loss, loneliness, a need for survival, strength and identity. The driver for the book is a frustration I have about being labelled as disabled and the connotations that come with that of needing help and not being able to do certain things. The central character of the book questions whether he is still disabled if there is no one to be compared to and also he pushes from one side of the country without help. There is not a week goes by where I am not approached in the street and someone asks me if I need help. I wanted to write about the freedom someone might have if that didn’t happen. What would they do and where they would they go.

HCE: What’s the best moment you’ve had in your writing career so far?

SL: Holding my first book in my hand will be a feeling that’s hard to top. I remember Clive Birnie from my publisher Burning Eye telling me at Verve Poetry Festival that I was going to be published and I was euphoric. It was only when I held the book that I actually believed it. Seeing people buy the book or react to the poems at readings is a thrill I would find hard to replace.

HCE: What type of poetry do you seek out for personal enjoyment? As a reader/listener, when you engage with a poet’s work, what are you hoping to get out of it?

SL: There are so many poets whose work I adore and am inspired by. In writing The Last Custodian I pretty much had collections by Caroline Bird, Mary Ruefle, Roger Robinson, Jay Bernard and Peter Gizzi on rotation. I love poems that tell you something about the ordinary that you hadn’t spotted, and I think all of those poets do that. I also enjoy being surprised by words or phrases used – a great image goes a long way for me and I try to replicate that in my work. There are also many disabled poets who I admire and think write amazing poetry. I’d love to namecheck every disabled poet but Ilya Kaminsky and Raymond Antrobus are huge inspirations, as are Jackie Hagan and Abi Palmer. Hannah Hodgson is also a poet who I am enjoying a lot at the moment.

HCE: You’ve managed to bring out a new collection at the tail-end of this pandemic era, during which some creatives struggled for inspiration. Any advice for people who are contending with writer’s block?

SL: Even with writing the book I still struggled with writer’s block. I try and look for inspiration all around me and am always making notes in my phone or notebook about things I find interesting. I’m never far away from a poetry collection and my best way into a new poem is to flick through another poet’s collection and find a word, phrase or theme that I like and try and emulate that. I might use the opening line of a poem and then discard it for a word that I like as a prompt and then see what happens. I also find free writes incredibly helpful as well. Just setting my timer for 5 or 10 minutes and seeing what thoughts I put on the page never fails to surprise me by what comes out. Also, I think Caroline Bird said use dreams as the first draft as a poem. I love that. Do that. It works really well.

HCE: In your experience, is Bristol a good place to be a writer and does it have a thriving literary scene?

SL: I don’t think I’d be the poet I am today without the support and kindness of the Bristol poetry scene. We are really blessed to have some incredible poets and some incredible events. I’ve learned so much from this community and one of the best things about the Bristol poetry scene is how much poets support each other and want them to do well. There are few egos here and I’ve had some of my best experiences on a stage at Bristol events. There is also a growing independent bookshop scene and plenty of novelists and playwrights as well. It’s a great place to be and I’d recommend to anyone wanting to pursue a career in writing.

HCE: Across the pandemic, virtual gigs have put all attendees in the equal position of being seated and only visible from the waist up. In your opinion, can anything positive come out of our lockdown experiences, in terms of disability and accessibility?

SL: Online events have to stay, it is as simple as that. During the pandemic I have got to feel what it is like to be able to attend or read at an event and not have to check whether the venue is accessible with wheelchair access. I’ve attended events from across the globe and it has been liberating, I’d be devastated if things returned to the way they were. This is not to say online events do not have issues, and we can do much more to make them accessible, but there is definitely a place for them alongside in-person events. How great is it that people in Newcastle can now attend poetry events in Newquay and not have to travel. It has opened up poetry to so many more people overcoming issues due to accessibility, location and cost. I appreciate there is Zoom fatigue but online events, run well, have a place to stay in the poetry scene. One thing we can do is listen to what the audience wants. I ran a survey recently about online events and found that whilst most people are happy to pay around £5, there is a desire to see events that are between an hour and ninety minutes. And where some sort of accessibility, especially captions, is thought of.

HCE: It’s becoming a slightly better question to ask and answer, compared to earlier in 2021…what is next on the horizon for you? Are you already working on projects/booked for upcoming performances?

SL: I’ve been lucky enough to receive Arts Council funding to help with some online launches for the new book. Over the summer there are going to be a series of events, dates TBC, all of which will be online. There is also going to be a podcast to go with the book, some short films and an audio version of the book I will be recording on to vinyl. I’d still love to be booked for some in-person events, so anyone reading this, feel free to get in touch! I’m also really excited to be poet in residence for Camp Kin at the end of July, and in August I’ll be performing a new piece of work for Coventry’s Theatre Absolute on the disability benefits process. This is part of their Humanistan programme and I cannot wait.

HCE: What’s the best way for people to keep connected or contact you for bookings?

The Last Custodian and Only Air are available to buy from Stephen’s website (which also has signed options, or a bundle offer if you buy both together!) and all reputable book retailers.