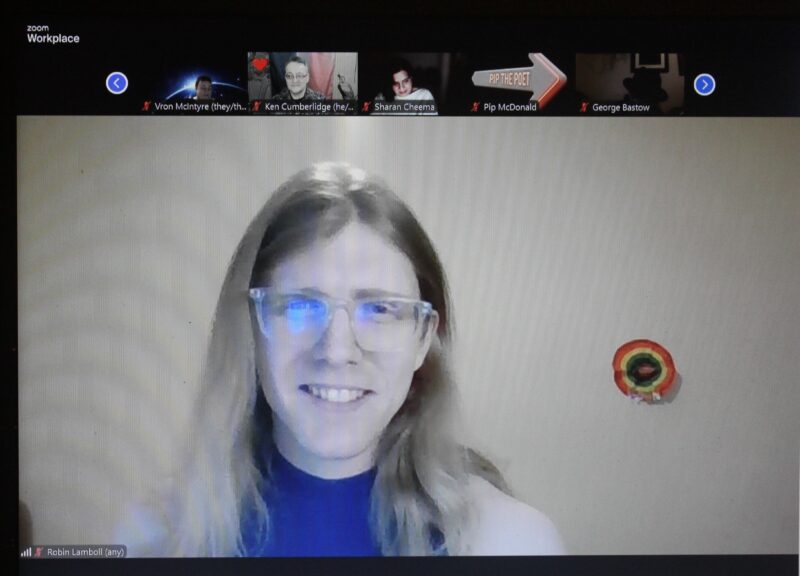

INTERVIEW: ROBIN LAMBOLL AT FIRE&DUST

Dr Robin Lamboll is a research fellow studying climate change at Imperial College London, and writes poetry inspired by the intersection between the human and natural world. Robin has won the UK, Vogon and Madrid International poetry slam finals, and came second in the World Cup of Slam in 2019. They have given a TEDx talk on science and poetry and been published across the web including Perverse, Experimental Words, Eunoia Review and Consilience and have performed science-inspired poetry everywhere from Lovebox festival to academic conferences and COP26.

In June 2024, Robin was the guest headliner at our virtual Fire&Dust poetry night. We caught up with them after the gig, to ask a few questions…

HCE: Tell us a little about your background and journey as a writer so far. What inspired you to start creating and performing poetry?

RL: I started writing poetry and fiction from a young age, but by university mostly was caught up with science writing. I only got serious about poetry during my PhD. A friend of mine put on a poetry slam in the same week as I was in a science presentation competition and I thought, why not work on both at the same time? I didn’t win either contest but got lots of good feedback, so I kept going with it!

HCE: Do you have an ideal audience in mind when you’re putting a poem together?

RL: I try to write for the audiences I see most often – people who are curious and a bit geeky, but don’t necessarily have a background in science or poetry. I also try to give poems levels – it’s OK to have some in-jokes or technical references for people who are more familiar with a subject, or people who are listening for the second time, but there has to be a layer of the poem that entertains everyone who’s going to hear it. No one will understand everything you want to say, but if you don’t want to be understood why are you on a stage? A lot of it is working out how to trust your audience without assuming too much of them.

HCE: Are there themes or motifs that you tend to gravitate to in your work?

RL: Science is a big theme for me, in all of its many facets – as well as its intrinsic beauty, I’m fascinated by the wealth of metaphors. I write a fair amount about queerness too, though I feel like I have more competition for that theme amongst other poets! As a climate scientist, nature and climate change are also recurring themes, though I don’t usually like to feel that my poetry is an extension of my work.

HCE: Talk us through your writing process a little. What most inspires your ideas for poems? Do you experiment a lot or make radical changes to early drafts?

RL: It depends on the poem, often they’re triggered by reading some scientific research. A few of the poems are basically stories that just come into my head, but most of the time I have a concept for a poem and sit on it for a long time. Then it will collide with another concept and I’ll get excited enough about the ideas to actually write the poem. If the poem is densely rhythmic or has some sort of linguistic constraint, I’ll tend to rewrite it a lot until the flow is right – I can’t stand poems that rhyme but don’t have some sort of rhythm, and usually find that stricter is better. Sometimes you don’t know whether it’s right until you’ve performed it a few times and find where your tongue trips. Memorisation is the final stage for a poem I want to slam with. It marks the ossification of the poem, but you also notice that some lines are harder to remember than others; often this means that they’re not that good and are just filling space.

HCE: You have a good track record when it comes to poetry slams, as a winner of both national and international events! What are the big differences for you, when it comes to choosing poems to perform for a headline set vs. poems for that competitive side of the spoken word scene? And it is helpful to have a scientific/methodical mind when it comes to preparing for slams?

RL: There are a few very specific types of poem that tend to slam well – poems that take up as much of the 3 minutes as possible, poems that appeal to a wide range of typical poetry audiences, and poems that have dramatic effects on the audience. When crafting a set, you can explore a much wider range of poetry in terms of length and style, as well as taking more risks and reading more fresh material. One thing that I really appreciate from slams though is the numerical style of feedback – people can really sugar-coat what they say about a poem, but they don’t sugar-coat numbers. It’s important not to treat the numbers as judging the inner value of a poem, but they capture something about how this audience is responding to the poem, and you can work with that to find stronger and weaker poems for this type of audience. I think science is more favourable for negative feedback than poetry, because science is always a process of getting better and is never finished, whereas poets want a poem to be a lasting monument. Realising that it can’t be is part of the process of getting better!

HCE: What, in your opinion, do most well-crafted poems have in common?

RL: Poems can be well-crafted in a huge range of ways, but something that they usually have in common is a high degree of attention. Sometimes that’s to language itself, sometimes that’s to the inner feelings of the artist or to something they want to capture.

HCE: Do you have an example of a science poem or science-focused poets you love, other than your own work?

RL: There are loads of really cool science-poetry collaborations! Some great science poems include ‘Antidotes to Fear of Death’ by Rebecca Elson, various poems in Rick Dove’s Tales from the Other Box, and there’s a whole poetry journal called Consilience devoted to science poetry!

I also don’t know that there’s a really hard line between science poetry and nature poetry in general, such as by Mary Oliver. It’s all about drawing inspiration from reality.

HCE: Do you think poetry and science offer complementary ways to make sense of the world? And is writing poetry a creative outlet you ever recommend to other scientific minds?

RL: I don’t know that poetry always makes sense of the world, often it makes the world harder to understand. Of course, sometimes science does too! For me it’s more about making connections from how things are to how I feel about them. I have recommended poetry to a number of scientists, but have to say that the uptake rate has been quite low.

HCE: In your opinion, what more should arts communities be doing to support LGBT+ poets and writers, to make sure their voices are platformed and heard?

RL: I think it’s very dependent on the platform. In spoken word circles, LGBT+ people are if anything over-represented, and that spans across levels. Representation is lower in published page poetry, particularly as you consider more canonical or “higher-ranked” poets, but to be honest other art forms have it much worse. Part of this is simply that poetry isn’t professionalised in the same way as, say, the music industry, and so is much richer in terms of providing havens, allowing diverse and jagged people a space to express themselves. The downside of this is that poets and writers (of all sexualities) aren’t supported financially to make this their main career.

HCE: What’s next on the horizon for you? Are you already working on a new collection/project or booked for upcoming performances?

RL: I’m putting together a collection of poems about death from a physics-based perspective at the moment. I’m also starting to get into drag more!

HCE: What’s the best way for people to keep connected with you and your work, or contact you for bookings?

Linktree Bluesky Instagram Twitter Blog

HCE: Is there anything we didn’t cover that you’d like to share with our readers?

RL: I think that was a good range of questions!