INTERVIEW: FIRE&DUST MEETS MARTIN HAYES

Ox loved the fields

they gave him meaning

when all the leaky barn did

was pile hour upon hour upon hour of proof

that all he was

was an ox

the fields allowed Ox to stretch his loins out

use his bulk

to heave and heave

test himself

amongst other oxen

it was like a great big game

Ox knew that

but coming first was so important

so indecipherable

like discovering a very important message

in between the lining of your skin in between your guts

when all the leaky barn did

was reveal everything that had already been discovered before

over and over

again

there was an urgency for Ox

to find a different answer

having ruled out Redheads, Rebellion and Escape

Dreams and Hope had become his favourites

the two Unicorns

he’d chosen to ride him around the graveyard’s walls

into the field beyond where no one dies

it is a hard thing to do

find Unicorns

you have to start believing in them first

before they even start to appear

Ox didn’t have a clue if Unicorns existed or not

he just

wished it

–‘Ox maybe discovers Unicorns’

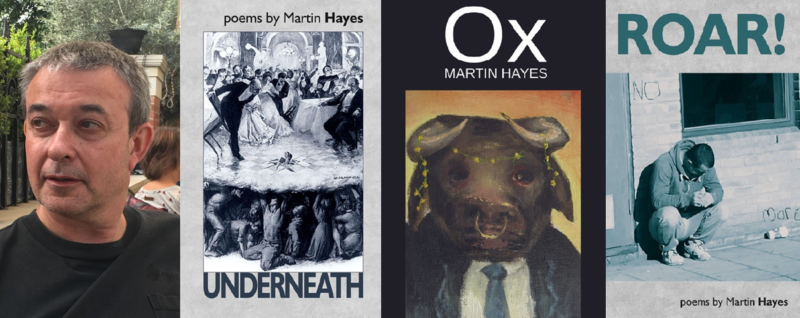

Martin Hayes was born in London and has lived around the Edgware Road area of it his whole life. He has been employed in the London same-day courier industry for over 30 years, and his poetry consistently reflects on workplace issues and culture. He is the author of seven collections of poetry, including: When We Were Almost Like Men (Smokestack, 2015), The Things Our Hands Once Stood For (Culture Matters, 2018), Roar! (Smokestack, 2018), Ox (Knives Forks and Spoons Press, 2021) and Underneath (Smokestack, 2021).

Martin was the guest headliner at our Fire & Dust poetry night on 1st December 2022. His ballsy, straight-talking words were well-received by the audience and we caught up with him after the event, to ask a few questions…

HCE: Who is your work aimed at – do you have an ideal audience in mind when you’re penning a poem?

MH: There is no ‘ideal’ audience I set out to write to. Any audience will do for me. Ha! I write for myself firstly. If there’s a thing that’s gone on that’s bugging me out, that I can’t fix or reconcile, I tend to write about it. Injustices get me the most. And apathy. I hate both and when I come across either of them, I like to try and solve them – play them out in the writing – use voices, that often go unheard in the grand scheme of things, to put their side of it across. If I didn’t have that outlet, I think I’d be a screaming, dribbling mess. Writing has definitely saved me from something far more grotesque and nullifying. It sort of gives me something to always look forward to. A bit like hope.

HCE: Do you enjoy the process of putting together a collection? Which has been your favourite so far, and why?

MH: Yes, I do like that. The process of putting together a collection is, for me, a bit like a hunter gathering up the beasts they’ve killed (a poem written) then hanging them on the wall in the order that tells the story best. I don’t like or condone hunting beasts, by the way – gotta be careful what you say nowadays – it’s just an analogy that fits how I feel about this. Each poem is like a beast (a memory) that’s been slayed, laying there on the page (first draft) then you autopsy and dissect it (the editing process) and if it feels good then you put it in a room (a folder on your laptop) and then when you’ve got enough, you go into that room and lay them all out to see if there’s a story to be told in there yet. If there isn’t, you keep on going out hunting the beasts (writing poems) until there is. It’s a process I really enjoy – a gathering process, the gathering up of memories; I really like it.

The favourite collection of mine, the one I enjoyed pulling together most, was The Things Our Hands Once Stood For. It was the first one where I felt that I was getting close to telling the story how it really is. For me, anyway. Mike Quille, the editor at Culture Matters who published it, he was very keen on using photographs to accompany the poems so I set about taking pictures on my phone around the neighbourhood and at work that could add to the poems – I loved that – then placing them all together in the right order. It felt good, like when I was a kid again putting together a Lego or Meccano set. There was a rush and thrill I remember from back then that bringing that book together rekindled. I used to save up pocket money and bits of hand-overs that my mum would give me when she’d won – and I’d save it all up and then when I had enough I’d go up to this old toy shop on the Finchley Road by Swiss Cottage called Toys Toys Toys – it was like a Mr Benn thing for me – full of stuff that made me excited…puzzles, board games, plastic monsters on top shelves with red eyes that used to bend down and roar at you as you walked past…it was an amazing place…and when I went in, I’d buy the biggest box of Airfix or Meccano I could get with the money I had then bring it home on the 113, carrying it up into my room where I would unwrap it, carefully lifting the lid up off the box, before tearing apart all of those plastic bags that contained all of those bits and pieces. No matter how hard I tried to keep them all together in their stations and appropriate sections though, they all became mixed up with each other all over the floor…hundreds of bits and pieces…but it didn’t put me off…I’d spend hours slowly partitioning them, trying to find out again where they belonged and, after 3 or 4 days, at the end of your effort, there was this thing suddenly in front of you that the big box you’d brought home had contained…only in hundreds of bits and pieces at first…then you picking up bits and turning them over in your hands…staring at them while held in your fingertips to see where they might fit into other bits…and when you found the bit they fitted into it all slowly began to start coming together. Then when you looked at the finished article…a car…a train…a Spitfire…the Maltese Falcon…you got this rush…that everything was OK…that you had done something…that you had done something with all of those bits and pieces and that maybe there isn’t an actual problem with the world as long as you can find a way to fit all of those bits and pieces together so that it’s all not so confusing. That’s how I felt putting together The Things Our Hands Once Stood For. It was a great feeling – one, that in the writing, I keep trying to replicate.

HCE: The courier industry seems so hectic day-to-day – how often do you get a chance to write a poem? Do you have a fixed writing routine?

MH: I only write on Friday nights and some Saturdays. Because of my work, I don’t get much time to write during the week. But I’m cursed – I mean blessed – with a 40-minute tube ride each way between home and work/work and home. I use that time to jot things down – then on Friday nights I look at what I’ve got and begin to work out if there’s a poem in there or not. Friday nights are my time, I guess. I get myself a couple of bottles of wine, sit down in front of the typer, and then I’m away…off with the fairies.

HCE: There are subjects and experiences you’ve focused on across your body of work so far but (prior to your collection ‘Ox’) would you say there were also themes or motifs that you gravitated to? And please tell our readers a little of the story that led to you writing ‘Ox’, which features numerous farm animal analogies.

MH: The theme I gravitate towards is work. In my job, working in the same day courier industry in London, there are so many people I speak to in a day. We have over 400 couriers who we are continually interacting with all day long to get the jobs that drop down onto our control screens covered. There can be a lot of negotiating, to get a courier to do a job they don’t want to do. Whenever you get a crap job that needs covering, that a courier doesn’t want to do, you have to remember all the good jobs you’ve given that courier before and remind them of that, and that also you won’t forget this one. They are gig-economy workers, so a crap job can hit their daily pay pretty hard. So you have to understand that but still be able to get them to do it. And all the while you’re doing this, you’ve got the supervisors behind you monitoring everything. And then there’s all the staff – we have over 40 in our control room – all under different/similar amounts of pressure to get what their job is done as well. Telephonists, right-hand men, account co-ordinators (they have to solve all the queries and complaints that come in – see potential problems coming over the horizon – so they can try and head them off before the shit hits the fan). Then there’s the recruitment staff, the international and overnight controllers, the salespeople buzzing around trying to look after their accounts. It can all get a bit frenzied in there at times and some people have difficulty handling it and some days they have a meltdown. Some supervisors can’t handle it either – and that’s when they get all agitated and bullying, coming out of their offices like moray eels to snap a head off here, break a spine or two there, screaming and shouting at the staff. Because they have their own dramas too – they must answer to the Directors if something goes tits up. And in all of that, you get this kind of big grotesque play going on, in which all of the participants are being pulled this way and that. It can feel like a kind of war, or at least a battle within a war, sometimes as well, with everyone trying to avoid any disasters. There’s a bit of friendly fire that goes on – when people are placed under pressure, under such scrutiny, they can get confused and take a colleague’s legs away in the hope of self-preservation. This is a difficult thing to understand, but it exists – the skill is in being able to pull it all together, make it all happen, like it’s the same as going into a shop and buying a can of coke – and when it all goes right it can feel like you’re a part of a great big orchestra in the Royal Albert Hall where all of the players bring together the most beautiful symphony. This is the world I know, so I use it as a kind of stage, as the point of familiar reference, to share the ideas and stories I want to get across in the writing. I think when writing about real people and real events it is better for a writer, for me anyway, to use a situation they know about rather than projecting something unfamiliar to them onto the page that may not then come across as authentic.

The story behind Ox, briefly, is after the book Roar! came out I got this warning letter from my work for bringing the company into disrepute. The CEO of the company chanced on a copy of it that a colleague of mine had left on the kitchen side. (Friendly fire…ha!) He then called me into his office and started asking me questions about it. “Who’s this poem about…what’s that poem about” kinda stuff. Telling me that I’d betrayed the hand that feeds me. A lot of shit went on after that. But in the end, after a lot of HR stuff, I got this written letter of warning telling me if I continued to bring the company into disrepute with the writing then I would find myself going through a disciplinary process that could end up with me losing my job. So, not wanting to lose my job, but also not wanting to stop writing either, I came up with Ox, which is a kind of fable using metaphor, allegory and fairy tale rather than the plain simple poem/language contained in Roar! I guess you could say that Ox got written because of censorship. Or at least because of the threat of it. I wanted to say the same thing but needed it to go under their radar, not be so obvious, to protect my job and, most importantly, to continue having something to write about.

HCE: The story-telling nature of your poetry is reminiscent of Bukowski. However, whereas Bukowski tended to keep his characters anonymous, we’ve noticed your poems often kick off with and repeat the name of the respective protagonist. Do you feel giving names to characters plays an essential role in connecting readers to the real, human side of your narratives?

MH: Yes, I like using names, I feel it gives the poem a different kind of energy or feel to it when you have to voice the name of who it is actually about. I mean, what use is a story if you can’t identify with the protagonist and characters in it? I think using names helps that process along – it helps the moment the poem is trying to capture become more than just an article of the writer’s faith. I’m a bit tired of writers who constantly want to tell us how they feel. Though I’m not naïve enough not to recognise that how the writer frames the story or poem is a reveal on how they feel about the thing they’re writing about, I also think that the poem should bleed the story through using character and plot rather than use all these I’s and I am’s. To write a poem about a character then to have that character pop up in a poem 20 pages further into the book, then again 5 pages further in, then to have the same thing happen with 10 other people, and then to bring them up in a different collection, so that they are all swirling about, all coming in and out of the story at the moment they are needed – it excites me, it feels more alive. It’s the story being told.

It’s just my thing, mind, I’m not saying that everyone has to adopt this strategy. It’s just with what I write about, this happens because I am writing about people I meet and talk with every day, so of course they are going to come in and out of the poems at various moments that fit in with the story – that’s only natural, isn’t it?

HCE: In your experience, is London a good place to be a poet/creative? Have you felt nurtured, and is there a thriving arts community?

MH: London is a bit like the Cinderella story. It’s full of ugly sisters running around trying to find the glass slipper to wedge their ugly foot into so that they can then run around saying, ‘Look at me! Look at me! I’m the one!’ Trouble is, it rarely fits – so you’ve got all these people either running around trying to find the glass slipper or else running around with a glass slipper on that doesn’t fit. Apart from the very locale, the neighbours and immediate community, it is a bit of a fake society. So multi-layered, and impenetrable now, it has (ever since the 2000s), begun to confuse everyone to the extent that you get the feeling sometimes that everyone just operates on their own level of Hell and makes the best of what they’ve got. I do love it at times, though – but the amount of life and energy going on is proportionate to the pain – it is a driving force, something I have been a part of all my life, so you can’t just slag it off. It’s just I’m getting a bit older now and it can all get a bit tiring and seem pointless sometimes.

I don’t know much about the thriving art communities in London, so can’t really comment anything constructive on that. I speak quite a bit with friends I have made since I started writing but we don’t meet often, it’s more a virtual friendship of sharing and caring and joking about a bit. I resigned myself long ago to a life of work/home, work/home, help those you can and then write write write. Anything bigger than that and it just annihilates me. I want to sit still and let the slow peace of a Friday night wash over me – it’s really all I want from the writing – hopefully let the magic find me in that time and then do something positive with it. I am nurtured and inspired by that I guess – by that, and the wine of course.

HCE: Your poems tackle a lot of anger-inducing social problems and struggles. Do you wish other contemporary poets would be angrier in their work and strive to be a voice for political change? For instance, poems in ‘Underneath’ explore the negative impact and experiences of the pandemic lockdowns on workers, and not many writers seem willing to hold up a mirror to that side of events.

MH: The poets will write about what they want to write about, and the editors will publish what they think their readership wants or needs. What I write about – that’s just my thing. I personally don’t think we’re gonna get any time soon waves of poets coming out…how did you put it…‘wanting to be angrier in their work and strive to be a voice for political change’. They’re poets, after all. To write about ‘negative-impact’ events is not on their poetry agenda. Though they might feel and understand this on a personal level, the poetry ‘establishment world’ they want to participate in does not; it doesn’t really want to get entangled in anything too messy or too political, for fear of upsetting all kinds of people, institutions or trusts. And it’s fine. As I say, writers should be allowed to write about what they want to write about to achieve what they want. Without that licence it would be a kind of censorship, a totalitarian regime. Forcing its criteria and subject matter on poets, of which they are only allowed to write about under threat of exclusion and banishment, would be far worse wouldn’t it? 😉 It’s just not my thing – to write to fit in – but it is for a lot of people and that’s fine – but for me poetry should certainly challenge these things but must at all costs avoid becoming like a preacher’s voice in his or her pulpit administering a sermon bordering on a rant. For me, it should be one of the instruments we use…after a couple of glasses of wine…which we use to bring together those oft-lost components of the human mind/heart – which is relevant insight that leads to communal solidarity.

HCE: What, in your opinion, do most well-written poems have in common?

MH: A story. Tell it plain and simple and people will listen to you. Throw a bit of magic in there also – a killer line or two – an image that they can visualise and feel because they’ve been there as well. Make it relevant – and people will listen to you even more.

HCE: It can be difficult to balance our writing ambitions against the stresses and responsibilities of working to pay the rent, etc. In your opinion, what more could the world of poetry be doing to represent and appeal to working-class lives and voices?

MH: There is a book called The Iron Moon which is an anthology of Chinese worker poetry and there is a poem in there called The Obituary of a Peanut by a writer called Xu Lizhi – here’s the poem below…

Obituary for a Peanut

Merchandise Name: Peanut Butter

Ingredients: Peanuts, Maltose, Sugar, Vegetable Oil, Salt, Food Additives (Potassium sorbate)

Product Number: QB/T1733.4

Consumption Method: Ready to consume after opening the package

Storage Method: Before opening keep in a dry place away from sunlight, after opening please

refrigerate

Producer: Shantou City Bear-Note Foodstuff Company, LLC

Factory Site: Factory Building B2, Far EastIndustrial Park, BrooktownNorthVillage, Dragon

Lake, ShantouCity

Telephone: 0754-86203278 85769568

Fax: 0754-86203060

Consume Within: 18 Months

Place of Production: Shantou, Guangdong Province

Website: stxiongji.com

Production Date: 8.10.2013

This poem, and others in the anthology too, but this poem especially, seemed to me when I first read it to use, and be written, from an entirely different source from what is considered acceptable subject matter in mainstream poetry. For me it was written from the guts first, from an almost helpless place where the subject matter found the poet rather than the other way around. For me, if the poet has to search inside them for a subject matter to write about then it’s already over. Using the simple description of the contents of a jar of peanut butter from the label on the back – I thought this very imaginative and authentic – a worker on the assembly line of the Foxconn factory in China, which is the biggest manufacturer of Apple components in the world, that hundreds of thousands of us hold in our hands and tap away on, products that have become the single most important interface for them into the world – using the death of a peanut, crushed into a mixture of butter, maltose, sugar, vegetable oil and salt then encased in a jar, with the sell-by date and place of production included – I thought using that to highlight the crushing nature of the writer’s existence as a worker in that factory very inspired and relative. It’s like the writer is identifying that he’s a product too. Unfortunately, I don’t think this anthology will ever be read by the wider audience it deserves despite its original power.

Also, the Bread & Roses Anthology – which is a collection of chosen poems taken from entrants to the B&R Poetry Competition every year – consistently, every year, produces some of the best writing around. There is a great bit on the Culture Matters website about the yearly project, worth quoting here, which I think sums it up well…

In the first quarter of the twenty-first century, it is hard to hear anything against the continuous white noise and shouting of barefaced political lies – especially from the Tories – through PR, advertising and social media. There are so many words saying nothing, and too many contemporary poets add to this white noise, writing about themselves and their private dramas.

I think publishing more poems like the ones in The Iron Moon and the Bread & Roses yearly anthology is something the poetry world could do more to appeal to working-class lives and promote working-class voices.

HCE: What would you say is the best accident or unplanned event that has helped your writing/writing process?

MH: Watching Deana Lay do trampolining at 5th year in secondary school. I was supposed to be doing cricket but the week before I’d bowled a beamer at this nasty piece of work who’d been bullying me in the playground on account of me wearing dodgy cheap trainers – I had those Tesco canvass ones with the red line that went around the whole shoe put peeled off at first impact with anything – and the beamer knocked him out and caused blood to come from his nose. I was handy at cricket – played for Middlesex Colts – and Mr Hughes our PE teacher new that so new that I was lying when he questioned me and I said that the ball had slipped out of my hand. The punishment was no cricket so the following week I was put in the trampoline class. That’s when I saw Deana Lay do her trampolining. She was amazing. Wearing cut-down jean shorts and one of those blue suede Fila tracksuit tops that Bjorn Borg wore at Wimbledon. The way she bounced up and down doing star shapes in the air then landing back down on her back only to shoot up again and turn a 360 in the air. I was sitting on the benches that lined the circumference of the gym felling all moody and hurt because I wasn’t allowed to do cricket – it was torture for me. But when she came on and done her stuff, I knew it was beautiful, like a piece of art. I didn’t know it then obviously but later after I’d visited the museums and seen Titians’ Assumption of The Virgin and Rembrandt’s the sacrifice of Isaac, I knew…I knew then that I’d seen a piece of art back then. So if you asked me what is the best accident or unplanned event that got me into poetry I’d have to say, in hindsight, thinking back on it now, it was seeing Deana Lay doing trampolining in 5th year of secondary school. It’s where mind and beauty and meaning first attached itself to me…it was the first moment I can remember that I had to really think about things, and all because I’d been banned from doing cricket.

HCE: Poets too often fall into the trap of ‘preaching to the choir’ and end up bombastically stating the obvious…which evokes applause, but usually not new understanding or empathy. Your work negotiates keeping the message accessible while also achieving originality and nuance. Do you have any advice for poets on how to achieve that?

MH: This is a difficult one for me. I see advice, framed in the way you’re asking this question, as a kind of ‘preaching’ in itself. What do I know? I know what I want to write about, but that’s my thing. Martin Malone, who is a man I respect as a writer, but also, and more importantly, as a human being, told me in a roundabout way that under all circumstances you must avoid becoming a gatekeeper with the only key. So I can’t answer this one. It’s up to the writer to find it. But if you pushed me, I’d say just write about how it is for you. If you’ve got it, it’ll come out of you. Someone once said that if you’re going to try, go all the way, or don’t even bother trying. That’d be my advice.

HCE: What type of poetry do you seek out for personal enjoyment? As a reader/listener, when you engage with a poet’s work, what are you hoping to get out of it?

MH: Magic. I like lots of lines about nothing much at all and then at the end of it there is this thing, this magic line, this magic image, that lights up the whole of the world and brings all of what has gone on before suddenly TOGETHER!

R. S. Thomas and Fred Voss are a constant foundry for me – Holub, Simic and Bukowski too. I read them and they connect with me on a different level than other writers do, and then suddenly I’ve got something else to think about! I also like some writers who aren’t so well known, who I’ve come across since I started writing. Paul Tanner, Peter Raynard, Steven Bruce, Fran Lock, Antony Owen and Ross Wilson are poets who I think deserve better recognition than they have received. Again, I think the subject matter they have chosen to write about, or which has chosen them, doesn’t quite fit in to the mainstream editors’ ideas of what is good for their readers and the reputation of their publications.

What would you say are the biggest influences on your approach to writing?

MH: If you’re asking about what got the engine ticking over in the first place then it was the songs and music – Paul Weller and The Jam, Joe Strummer and The Clash, Jim Morrison and The Doors, Ray Davies and The Kinks. The poetry thing came later. The music came first and then the poets/poetry followed – which is still true to a large extent for me, even now.

HCE: What’s next on the horizon for you? Are you already working on the next book/project/booked for upcoming performances?

MH: I have a little book/pamphlet coming out online this month with Culture Matters called Machine Language. Fran Lock has written an introduction to it and Martin Rowson has done some superb illustrations to complement the poems. It’s mostly about how, I think, we are being forced to buy in to new technology and how that is affecting us, changing us, as human beings – what we are losing because of it. And how everyone seems, because of economic necessity and our pleasure drive, to just keep on embracing it – assimilating it into their consciousness – so that the end result is that we’ve already become quarter human and three-quarters machine without really even knowing it. Some of the poems have an angry cynical tone because also there are many who seem to be embracing this shift from pure human intervention to algorithmic suggestions which is, for me, a bit of a decline. So the poems try to deal, in a round about way, with that little bit of us, that human part of us, that is left behind…left in the guts or the heart…that, hopefully, they’ll never be able to get at to destroy, and assimilate.

HCE: What’s the best way for people to keep connected with your work or contact you for bookings?

My Facebook page, I guess. I don’t send poems out to magazines or push things to do with the writing – I just don’t have time to find them in the ‘identifying way’ of finding the ideal target…who the fuck does…the work the kids the life…that is what I hope everyone will find in my writing…that it is just done on a Friday night after the working week has ended and I hope it represents that…Raef is my witness here…it’s taken me more than 3 months since I did the F&D reading just to get back these answers to his questions…I don’t know what it is…time I guess…I just drink wine and then post a poem up on Facebook on a Friday night while waiting in the shrub for another beast/a bit of magic to pass by so that I can kill it, net it up, and then have another one for the story/book I want to tell sometime in the future.

But also, Culture Matters – if you don’t want to buy one of my books – which I wouldn’t blame you if you didn’t – but if you did want to get a flavour of what I think it’s all about – in the writing sense – then it’s all free and available on the below CM link below.

Have a good evening, Compadres & Comrades…Ladies & Gentlemen…Mork & Mindy…Action Men & Sindy… 😉

HCE: Is there anything we didn’t cover that you’d like to share with our readers?

MH: No – I think I have bored everyone enough already.

But these ones too…

Martin’s books are available to purchase online, direct from publishers Knives Forks and Spoons Press, Smokestack and Culture Matters as well as other bookshops and retailers.