INTERVIEW: FIRE & DUST MEETS MARTIN FIGURA

Award-winning poet Martin Figura was born in Liverpool and lives in Norwich, with Helen Ivory and sciatica. Together they began hosting Live from The Butchery Zoom readings with renowned guest poets during the UK lockdowns, winning the 2021 Saboteur Award for ‘Best Regular Spoken Word Night’. Martin’s collection and show Whistle were shortlisted for the Ted Hughes Award and won the 2013 Saboteur Award for ‘Best Spoken Word Show’. He later published collections Shed (Gatehouse Press) and Dr Zeeman’s Catastrophe Machine (Cinnamon Press) in 2016; the show Dr Zeeman’s Catastrophe Machine went on to be shortlisted in the 2018 Saboteur Awards. Martin became Poet-in-Residence for Salisbury NHS Foundation Trust in 2021 and was commissioned to write poems based on staff experiences of working through the pandemic; this resulted in his pamphlet My Name is Mercy (Fair Acre Press) and inclusion on the Poetry Archive. His new book, The Remaining Men, was published in February this year with Cinnamon Press.

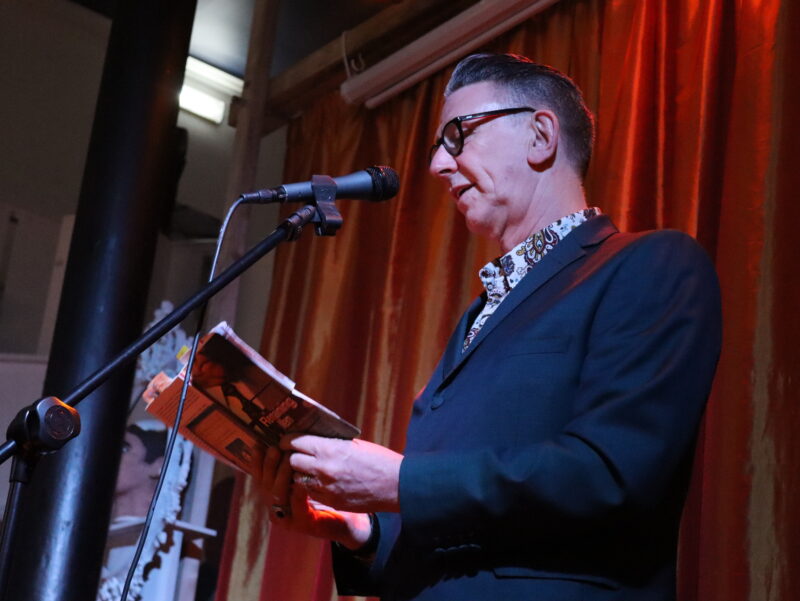

Martin was our Fire&Dust headliner at Coventry venue The LTB on 2nd May 2024, where his readings were well-received by the crowd. We caught up with him after the gig, to ask a few questions…

HCE: Tell us a little about your background and journey as a writer so far. What inspired you to start creating poems and poetry shows, and how did you initially find your way to spoken word events?

MF: I did of course write terrible teenage poetry – who didn’t. I even paid to be included in an anthology. I returned to it as I approached 40, with the aim of being able to show off – which I’ve been doing ever since. Performing is the part of the process I enjoy most. Things got serious after a while – and I set out to write about my childhood, the death of my mother and what led up to that, and what followed. I was mostly writing funny performance stuff then, which was not the right vehicle for the subject. I had a hoard of photographs from my father, who photographed everything, and this was a vital source. There was an MA at Norwich Art School called Writing the Visual run by George Szirtes, which was perfect. I focused on putting a publishable collection together first – that being the higher bar in my mind, but I always had some sort of visual presentation involved. Norwich was crammed with some of the very best spoken word artists – John Osborne, Luke Wright, Tim Clare, Hannah Walker, Molly Naylor. I got to see what might be possible and set off towards that.

HCE: Who is your work aimed at – do you have an ideal audience in mind when you’re putting a poem together?

MF: Not really, I’m glad to have anyone read my work. I try to make poems that can be enjoyed by the ‘poetry savvy’, but are not too coded to be alien to a general audience.

HCE: Would you say there are themes or motifs that you tend to gravitate to in your work?

MF: I do small human stories really, whatever the subject. That’s what interests me, and however grand the subject, they have a beating heart (or did once). Ordinary people is the main theme. Socio-political in broad terms. I’m not sure if the language of photograph can be deemed a theme or a motif, but its lexicon allows me to sometimes say the unsayable. I worked as a photographer, in much the same way as I operate as a poet now.

HCE: Are you able to share some insights with our readers about the premise of your new collection, The Remaining Men?

MF: The title poem refers to miners left over after the pits closed. I was commissioned as a photographer by Side Gallery in Newcastle to create work in a former mining village Horden, just a few years after the pit closed. I noticed men just stood about the place as if they’d been leftover. So, one theme is the way the changing face of work has discarded those men who worked in traditional industrial roles.

But there are a number of themes, that somehow cling together – to form some idea of how Britain – or England mostly – has gone since 1956, the year I was born. There’s a revisiting of my personal story in one section and a look at political leaders in another.

HCE: What have responses to the book been like? Are readers connecting with the material in ways you hoped they would?

MF: So far they have – it has had a very positive response and the reviews so far have been really kind I’m pleased to say.

HCE: Much of your collection The Remaining Men explores the human stories of other people, but there are elements of personal history in there as well. Your poems about difficult times in your life come across as authentic and honest while you also avoid angst and being overly confessional. What is the top piece of advice you can offer poets for how to achieve this when tackling autobiographical topics?

MF: Subtlety and understatement – trust the reader and leave something for them. Don’t over dramatise or harangue the reader (they didn’t do it). Don’t look to blame, look to understand. Or if you want to make a lot of money out – do the opposite.

HCE: What was the experience of being Poet-in-Residence for Salisbury District Hospital during the pandemic like for you? Can you share some details and highlights of what that role involved, and what sort of impact it had on your practice as a writer?

MF: It involved a few visits, and some thirty hours of interviews for front line staff. The impact on staff across the board, was palpable. There was a mixture of pride and despair – they also knew that there was another wave in the waiting list and that once it was over, there’d be no time to recover. The time I spent with the End of Life team was one of the most extraordinary experiences I had. To go back to the previous question – I’d like to quote from one of the poems, which is a direct quote from what the head of the team, Hannah McLean told me:

I had to hold the phone for him, and he was saying

when to plant the begonias out and don’t do it too early,

and then his son said I’m going to miss you dad

and he said you can do this.

That for me was more moving than anything I could make up – so simple and undramatic, it goes right through you.

HCE: In your opinion, what should our arts communities be doing to ensure the compelling voices and stories of more people from a diverse range of social situations (such as the NHS staff and army veterans from your new collection) are platformed and heard?

MF: Well, I’d say support events like Fire&Dust – I was amazed and moved by how supportive the event was. A week earlier we’d been in Cleethorpes and found a very similar vibe there, on a project run by the library. Unusually, older men were at the heart of it. Neither event was what you would call fancy (apologies) but I was heartened by both of them, and felt privileged to read at them.

HCE: On a lighter note, was it exciting to have Oscar winner Olivia Colman record readings of two of your poems for the launch of My Name is Mercy?

MF: It certainly was – I’m usually a bit wary of actors reading poetry, they will act! But she did a good job, and I made her cry.

HCE: You’re a social documentary photographer, so a visual artist as well as a poet – do you find these two interests complement each other? And which medium do you generally find most effective as an outlet for self-expression?

MF: I don’t really photograph anymore, now I have a way of making less money. As I said in an earlier answer, I use the language of photography still, and use it metaphorically. I’ve found that the critical writing of poetry and photographer can be inter-changeable. Books like Roland Barthes’ Camera Lucida and Raymond Carver’s Fires are useful in both mediums.

In the process of the NHS and Army commissions, I also came to the earth shattering realisation that I was operating very much like I did as a photographer – talking to people then constructing an image / poem. This suits the kind of writing I do very well, and complements sitting at the screen trying to imagine things. See End of Life quote earlier.

HCE: Would you say Norwich is a good place to be a poet/writer, and is there a thriving literary scene in your local area?

MF: It is fabulous, you can’t move for writers. There’s a Bloodaxe poet sitting 6 foot away from me now (Helen Ivory) – the streets are riddled with writers. The UEA Creative Writing degrees are partly responsible, but Norwich has been a hotbed of writing for centuries. Our workshop group has Esther Morgan, Tiffany Atkinson – both also Bloodaxe; Andy McDonnell (Nine Arches), Jo Guthrie (Pindrop) and Andrea Holland (Gatehouse) and George Szirtes, Cat Woodward, Jane Wilkinson, Julia Webb, Matt Howard and Moniza Alvi – I really could go on – and this is just the poets.

HCE: What’s next on the horizon for you? Are you already working on a new project/booked for upcoming performances?

MF: I feel a bit emptied out, I’ve performed my Covid delayed show Shed at Ink Festival and The Cockpit Theatre in London last month, and plans are afoot for it to tour next year – fingers crossed. I’m in the middle of a Norfolk poem commission – Helen and I are editing one of Candlestick Press’s forthcoming Norfolk Pamphlet. We’ve lots of readings to come, us on the road for much of the next year. I don’t have much writing planned – but am going to expand my poems about Amy into a wider context around Down’s Syndrome for a new show, beyond all that.

HCE: What’s the best way for people to keep connected with you and your work, or contact you for bookings?

Any of those – but Facebook is where I’m active, or my email.

HCE: Is there anything we didn’t cover that you’d like to share with our readers?

MF: I think you’ve got it about covered. A big thanks to you and your beautiful audience – it’s a fine thing you’ve got going there. And we loved Coventry itself.

The Remaining Men is available online direct from Martin’s website, as well as from publisher Cinnamon Press and other bookshops.