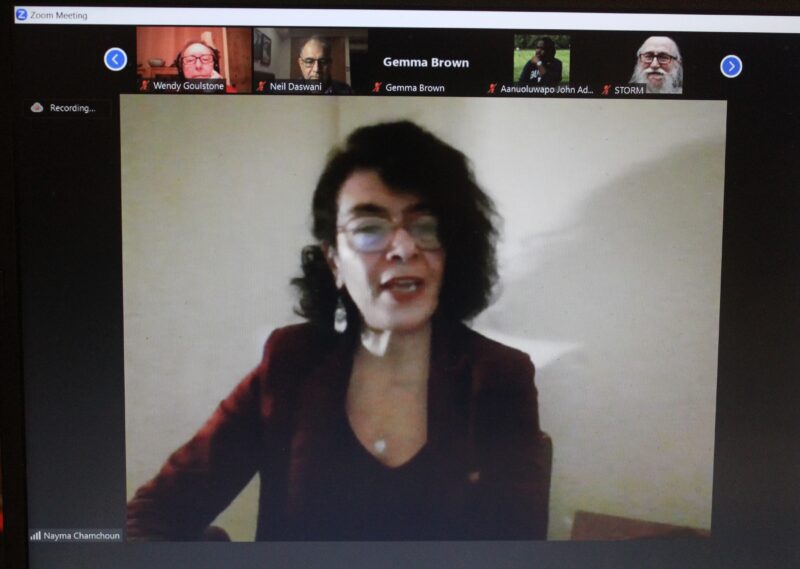

INTERVIEW: FIRE&DUST MEETS NAYMA CHAMCHOUN

Nayma Chamchoun is a British Moroccan self-taught writer and poet whose writing is influenced by her cultural duality. She is interested in female voices in the diaspora community, the challenges they face within both communities and the taboos around mental health within their ancestral communities. Nayma is an active member of London’s vibrant poetry and spoken word community, the international poetry community online and has performed her work at several poetry open mics, including an event for the Grenfell 5-year anniversary, and had her work featured on West Wiltshire Radio and BBC Radio London several times. Her published poetry collection Covid: The Wordy Wilds of a Mind Under Lockdown is a cultural fusion that explores themes of identity, duality, displacement, loss, race, feminism, culture, family, love and the search for inner peace as experienced alongside the effects of mental health, menopause, the pandemic and world events.

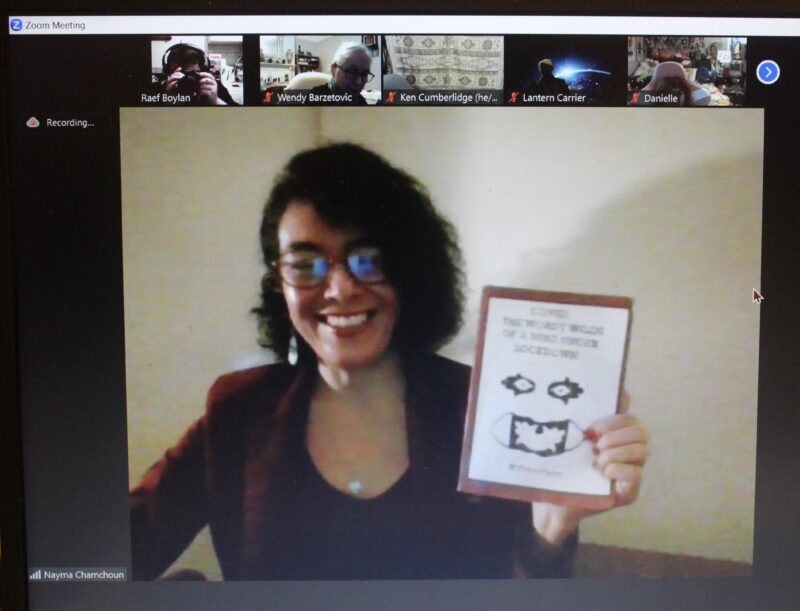

On 12th October 2023, Nayma was the guest headliner at our virtual Fire&Dust poetry night. We caught up with her after the gig, to ask a few questions…

HCE: Tell us a little about your journey as a writer so far. What inspired you to start creating and performing poetry?

NC: Gosh, my journey so far? It often feels like I took the very long way around and got a little waylaid. I think I’ve always written since I first discovered books, limericks, poems, short stories, Diaries and then after an enforced marriage at seventeen and motherhood I stopped, I even stopped keeping a Diary because the thoughts I had felt too sad to document. Then as demands on my time started to ease, I sort of gravitated back to writing. I started writing a novel but when Covid happened I returned to writing poetry, maybe because it was an emotional time that caused us all to look inward. I wrote a collection during lockdown Covid: The Wordy Wilds OF A MIND UNDER LOCKDOWN and after almost a year of rejections I was published by Mica Press. And since then, I just loved connecting with the poetry community whose warmth and support is both uplifting and inspiring and in itself creates opportunities to hone and grow in your skill.

HCE: Would you say there are themes or motifs that you gravitate to in your work?

NC: Yes, I think I do gravitate towards themes like identity, duality, displacement, loss, race, feminism, culture, family, love because I guess they draw from my emotional stream.

HCE: Who is your work aimed at – do you have an ideal audience in mind when you’re putting a poem together?

NC: I don’t think I have a specific audience in mind because often I just go where the poem takes me, but I feel there is an audience to my work, a current that appears, female voices in the diaspora community, the challenges they face within both their adopted and ancestral communities. A feminist voice.

HCE: What have responses to your first poetry collection been like? Are readers connecting with the material in ways you hoped they would?

NC: The response has been heartwarming. I’ve been able to perform my work on BBC Radio and at London Literary Week & The House of Commons. One person who read my book messaged me to say “You have a way of taking the most ordinary things and making them beautiful.” I loved that description of my work. After I performed No Filter at London Literary Week at Southbank, so many women came to speak with me afterwards to say how much it resonated with them. One woman said the poem made her feel heard and I loved that.

HCE: Talk us through your writing/editing process a little. Do you have different versions of your work ‘for the stage’ and ‘for the page’, or are there techniques to ensure a poem will engage audiences equally well in either context?

NC: My writing process is very haphazard, I usually get the first line or stanza and allow my thoughts to follow where it may lead. At that point I have no idea of where the poem will lead or what themes it will delve into. I will just allow the thought and emotion to lead and endeavour to make sense of the thoughts that follow. I usually have one version, the one that appeared to me, refined and edited to satisfaction. When I perform the pieces I try to convey the emotion through a more emotive and expressive delivery, emphasising certain points.

HCE: In an interview with Polis, you mentioned that you have a finished manuscript for your second collection and have been submitting it. Did it feel easier to assemble a collection second time around? What would be your top piece of advice for other poets on how best to approach publishers?

NC: I think writing COVID; THE WORDY WILDS OF A MIND UNDER LOCKDOWN certainly helped unlock and tap into the poetic thought process, which meant that I was feeling more inspired and motivated to write and I suppose the process of writing a collection and putting it together gives a structure and discipline to how you write and compile your work. So, in that respect, writing felt easier and the poetry seemed to flow more freely. Approaching publishers is still as difficult as it has always been. For me personally, I just edit and re-edit until I’m completely satisfied with the end product and just send out to anyone and everyone accepting unsolicited manuscripts. The rejections aren’t any easier and being published certainly hasn’t made the process any easier but if you believe in the work, you just keep knocking on those doors.

HCE: We’ve noticed that some of your poems are driven by a sense of social injustice and observations of inequality in the world. As a strong female voice, have you experienced backlash or a negative reception from any communities for being impassioned and outspoken about contentious cultural issues?

NC: Yes, not a huge backlash but certainly some disapproval towards the fact that I question culture and traditions that I feel disadvantage women. I’ve had some abusive messages or been accused of being brainwashed by western culture. I am not typical of women in my culture and am viewed as having strayed off the righteous path, but I can live with that because I feel that women’s voices within patriarchal culture need to be heard and acknowledged.

HCE: Surveys have identified women, particularly young women and teenage girls, as the biggest consumers of poetry in recent years, which has also been linked to a rising interest in politics. What do you think is the appeal for women of poetry as an art form? Do you feel a responsibility to be political in your work, and to verbalise collective experience?

NC: I think poetry appeals to women because women are naturally emotionally expressive and not influenced by typical gender roles. They are also able to express their emotions more freely without feeling judged as less, whereas men often are. Poetry offers women a creative emotional outlet and input and adds to our emotional growth. I don’t think I feel a responsibility to be political, but I may broach political or social issues in my work because they are issues that I feel strongly about and which need to be raised and discussed. If we look at the civil rights, beatnik or war poets they each offered an intimate and emotional narrative of the events of those times. A more personal experience than historical documents or news reports, an emotional experience which allows us to experience those issues through a personal lens.

HCE: Much of your poetry deals with your own experiences, such as arranged marriage and mental health – and, of course, the turbulence of family life under lockdowns – in a very raw and honest way. Is this an emotionally draining thing to do? What is the top piece of advice you would give other poets for tackling heavy/personal topics in their writing?

NC: Yes my work often stems from my own experiences because as poets we write about what affects us emotionally, joy, love, loss, injustice, trauma, sadness, mental health, etc. It is emotionally draining but it is also a very therapeutic process. It allows you to explore and make sense of those thoughts and emotions and give them some order, not only on paper but also with yourself. Some of the issues I explore, I was in denial about for a long time because confronting them felt too intimidating and they remained unresolved because I was too scared to delve into them and what they meant. My only advice would be that, yes, it is an emotionally gruelling process but it is also one that brings relief and allows you to make your peace with that trauma and maybe by sharing those emotions and experiences with others, they may also find some relief or resonance or inspiration in the work.

HCE: London is renowned for a thriving literary scene, and you are an active member of its poetry/spoken word communities. You also engage with a lot of online events based all around the UK and wider world. Have the COVID lockdowns had an impact on how much you travel in person to regions outside of London for poetry gigs?

NC: For me, my poetry journey started during lockdown in the writing stages and online performances then, after lockdown, at the in-person performance stage, so I wasn’t hugely impacted by travel restrictions because I was just beginning my journey during that period. The online Poetry community is a wonderful support both in terms of building your confidence, improving delivery, honing your skills but also in the support and opportunities it provides. When I started performing at London gigs, I was naturally nervous but not as nervous as I would have been without my experience with the international poetry community.

HCE: In your opinion, what more should arts organisations be doing to support women poets in the diaspora community, especially those aged 30+, to make sure their voices are platformed and heard?

NC: Maybe provide safe spaces within those communities that offer the opportunity to explore our voices and what they have to say. Workshops, writing courses, how to edit, access publishers, etc. Some may think that female voices in the diaspora community are too niche but I don’t believe this because I am also British, so my work is a facet of the multicultural British experience.

HCE: What type of poetry do you seek out for personal enjoyment? As a reader/listener, when you engage with another poet’s work, what are you hoping to get out of it?

NC: I constantly return to Eliot, I love the layers and the symbolism and the contrast of the banal and the grand and I always feel like I get a little something more every time I read him. Then of course there are the mystics – Kahlil Gibran, Omar Khayyam, Rumi, Hafiz, whose words bring such a contended peace and wisdom. Maya Angelou I can never get enough of; there is a strength, an illuminating power in her words, even in defeat.

HCE: What’s next on the horizon for you?

NC: I’m back re-editing my manuscript before sending it out again. I will be appearing on Spoken Label spoken word podcast on February 4th then at the Script Haven In Worcestershire on March 1st and a podcast on March 8th with the wonderful Dr Michael Anthony Ingram for International Women’s Day alongside some fabulous women poets – Marianne Teft, Phynne~Belle, Nona Lee and Jennifer Garnatz.

HCE: What’s the best way for people to keep connected with you and your work, or contact you for bookings?

Nayma’s book Covid: The Wordy Wilds of a Mind Under Lockdown is available online is available online direct from publisher Mica Press, as well as other bookshops and retailers.