INTERVIEW: FIRE & DUST MEETS MEL BRADLEY

(This is 'Dearest Women' in English. It’s the very last piece of the show, but in the show, it’s performed entirely as Gaeilge.)

Mel Bradley is a spoken word artist, writer, playwright/theatre-maker, multimedia artist and actor. She describes herself as a gatherer of the untold stories of women; an outspoken queer feminist performer with a candid voice and an unhealthy obsession in the Virgin Mary; and a creative genius with the attention span of a gnat, who began her spoken word career as a slam poet and now boasts three spoken words shows and a play. Mel also has a diverse background in devising and facilitating creative workshops for a wide range of groups and organisation, numerous schools north and south of the border and as an individual one-to-one mentor. As concept artist, she has created educational and outreach films, visual projections for theatrical performances using animation, motion graphics and other digital media. Her latest show For the Love of Mary maps a personal fascination with the Virgin Mary and her lost humanity, rediscovered in those stories shared by women living in Ireland and viewed through the lens of a displaced woman from a Protestant/Unionist background who has spent most of her life living in Nationalist (Catholic) areas in the North of Ireland.

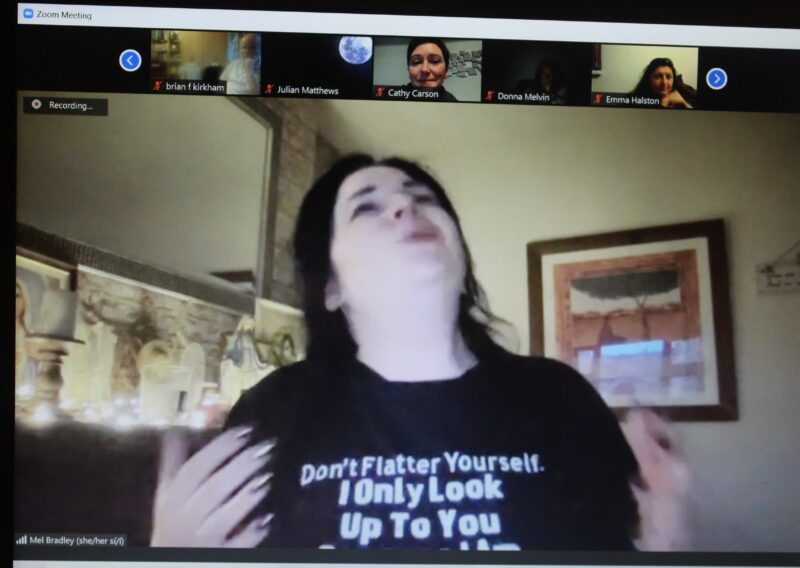

On 12th May 2022, she was the guest headliner at our virtual Fire & Dust poetry night. Her set went down well with the audience, and we caught up with her after the event to ask a few questions…

HCE: Tell us a little about your background and journey as a writer so far. What inspired you to start creating and performing poetry?

MB: I grew up hating poetry. I’m dyslexic and was always in a reading group of my own as a kid, so I didn’t enjoy reading much. In my teen years, my exposure to poetry was only in school and in a very prescribed manner. As much as I railed against my English teacher in secondary school, he taught me how to read Shakespeare and laid down foundations that would take 15 years for me to realise they were even there. I started writing Gothic horror fiction in my twenties and got persuaded to read my work at a night called ‘The Sunday Sessions’. It was my first time reading my own work in front of an audience. For a dyslexic with a fear of reading, it was terrifying. But it was there that I witnessed the most phenomenal woman, Debbie Caulfield, performing a piece called ‘Corvine’. What she showed me that night, was what poetry could do. Then when I was at college, doing the Access Diploma to get to university at the age of 29 years old, I spent a long an arduous night with Percy Shelley and Ozymandias and fell in love. It wasn’t long after that another friend gently nudged me (sort of) into doing a slam and the rest, as they say, is history. I love that I can say so much in a poem without having to give all the explicit details. That I can talk about hard subjects in a way that makes them accessible and based more in feelings than in text. That I can give people permission to feel.

HCE: Who is your work aimed at – do you have an ideal audience in mind when you’re putting a poem together?

MB: Me, I think. Um…I write because stories need to be told and often it will be because words have been clawing at the inside of my head. Or lines will be echoing in the distance demanding me to listen. Or I’ll hear something and it will niggle at me until I give in, pull the thread and see where it leads. One of the pieces that I shared at Fire & Dust – ‘Count The Seconds’ – was published earlier this year in an anthology about forgiveness, so I was invited to actually write that piece, but the inspiration came from a watching a documentary two years ago during lockdown: Athlete A. There’s a moment that happens when every survivor goes to tell their story. It’s this deep intake of breath and then the exhale before words can even find their way out in any concrete form. That summoning of courage and composing oneself to speak our truth. I felt a sense of recognition and knew there was something there. It took a while to find the right path for it, pull the right thread of story to tell. I use my platform to talk about the subjects that are often hard, so that if one person identifies with it, they don’t feel so alone. That maybe I can give words to an experience. And also, on the other side, if I can speak to a person who has never experienced that kind of trauma, and they hear it, gain an understanding, expand their perspective, then I’m doing something good, I think. Well, that’s my hope anyway.

HCE: Would you say there are themes or motifs that you gravitate to in your work?

MB: The kitchen table comes up a lot. It’s very much explored and explained in For the Love of Mary and also features in my first spoken word show You Maiden, I Mother. Religion, probably; I studied English and Theology for my BA, so it has a big influence on my writing. Abuse of power and the recovery from that. Women and womanhood. The untold moments. Those very human exchanges. In my first show, it was the female relationships in my life. My mother had passed away the year before and my daughter was growing into this amazing young woman, and just that journey of moving between the stages of being. My second show Ms Noir’s Seven Deadly Sins, was very much based on the religious idea of sin – it was really hard to try and come up with the story for Sloth (how does laziness condemn you to hell for eternity?) but I think I succeeded. The darkest thing I’ve ever written with some very strong female characters (the men folk didn’t come off too well in it at all). And of course, in For the Love of Mary, well, religion and women are front and centre of that one.

HCE: You mentioned at the Fire&Dust gig that your new show (For the Love of Mary) has been five years in the making. Can you talk us through the process of getting the show ready? Which stage(s) of development and production do you most and least enjoy?

MB: It started as a joke. Most of my major projects have started as some off-hand ‘wouldn’t it be great craic to…’ kind of comment. About six months later, I realised that it had the potential to be a really serious project and so I applied to Arts Council of Northern Ireland for some money. I spent about 6 months to a year travelling around the country and documenting shrines, meeting with women and having conversations, usually at the kitchen table with some tea. These conversations became a podcast series. I didn’t edit the conversations, I thought it would be wrong to do that. Then I used the themes that had come up in the conversations and wrote poetry inspired by them and by the women themselves. I knew that some pieces would be in a show and that some wouldn’t, some were more suited to being visually read. I really challenged myself with trying poetic forms I’d never attempted before, trying to find best form to fit the theme. I married the poetry with some of the images documented and created my first solo art exhibition with the work produced. Along with the poetry, hung as prints, it featured the podcast series on a listening station, a video installation piece (Sometimes the Story Will Find You) and we made an interactive digital shrine that you could use to send your petitions to Mary.

After the exhibition, I decided to quit writing, walk away from performing, find a new creative path. I was exhausted from all the research and really wounded by what I’d unearthed about the treatment of women. It was a weight that was so much harder to carry than I ever imagined it to be. But after a pep talk from a friend, I was back on the saddle determined to make it into a show. I took a 15-minute snippet to a scratch night, and tried it out, I got some really great feedback and encouragement, and then the pandemic hit. My attention got diverted slightly, I wrote another play during the first lockdown about what it’s like to be LGBTQIA+ living in Northern Ireland and put Mary to the side. Then I was granted an award from my local council to develop the script, the soundtrack and a mobile phone app. Yes, that’s right, there’s an android My Pocket Mary app and it’s on the Google Play Store. So, you can send your petition to the Marys that live on my mantlepiece. I also got a bursary to work with a mentor who gave me some tough but very constructive feedback. She said that it was a lovely collection of poetry but it lacked a backbone thread. That I had to tell my story, my journey and that I had to discuss the things that I had kept tucked away, the thing that I was incredibly ashamed of, my unionist upbringing. I should use it and let the audience see the Virgin Mary through my unique lens. So, I wrote seven new monologue pieces to frame the poetry and then learned it all, in five weeks. The very last piece in the show is performed as Gaeilge and was translated by a really incredible woman who is a native speaker. It took me two years to learn that. I had to actually learn what the Irish meant, not just the sounds. So, my three and a half years learning Irish has been part of the journey too.

HCE: We really enjoyed the sample of poems from For the Love of Mary you shared with us at Fire&Dust. What can audiences expect if they are lucky enough to attend a showing?

MB: Prepare to laugh and cry, maybe feel a little angry too. There’s a lot of emotion in it. You’ll go with me on my journey and there will be heartbreaking moments, but it’s nicely peppered with giggles and belly laughs too. There are so many voices in the show, that I think I move through quite well. There’s a beautiful soundtrack that was created by Siobhán Sheils of Great White Lies. She used somatic vocals to create this really ethereal atmosphere and it’s layered up with my voice speaking some prayers that I wrote (in the Shamrock pub in Falcarragh), based on the traditional prayers to Mary.

You’ll get to meet some really wonderful characters that will tell snippets of their stories. These are based on the various women that I sat with. Each character will leave something on the kitchen table as a symbol of that gathering. Wee Megan is adorable and one of my favourite characters that I’ve ever created. You get to meet my mum (not actually, she died, but me being my mum) as I share a memory of when I was fourteen and a story that my mum told me. I talk about the institutionalisation of women. I talk about the effect that partition had had on the role of women in Ireland, both north and south of the border. I talk about acts of devotional faith. Reflecting on the Decriminalise and Repeal movements. Grief, mental health, sisterhood, consent. It’s jammed!

There are snippets of Hebrew, Aramaic and Latin. Mary speaks. We follow her journey as well, through maiden, mother and crone/legacy stages and the final piece is her prayer to the women of Ireland for all the atrocities committed in her name. It’s performed as Gaeilge (although I shared the link to the English version on YouTube with HCE) because I wanted to decolonise the language. I wanted to speak to Irish women in this beautiful tongue and that just felt like the most authentic way to do it. Bring hankies.

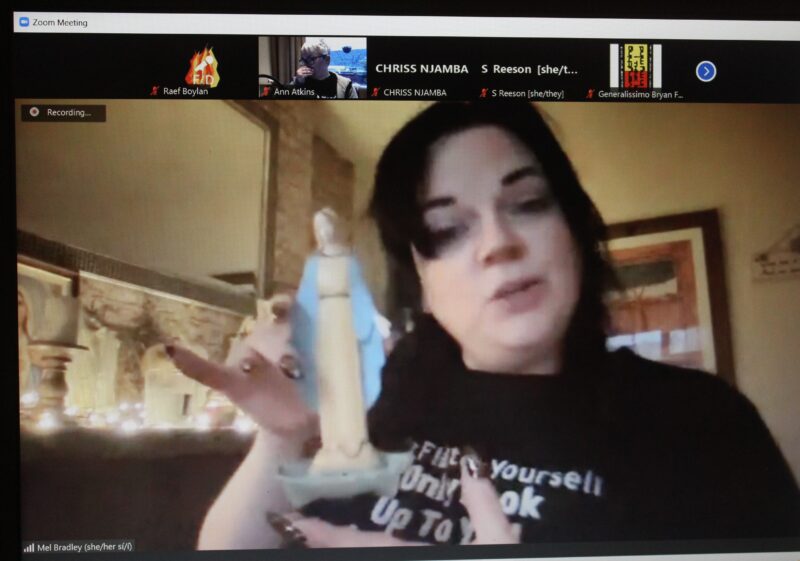

HCE: During the Zoom gig, you showed the audience some of your extensive Virgin Mary statues collection. Would you like to tell our readers how this collection got started – and is the Mary that is also a flask the most unusual one you own?

MB: She might be. All of the Marys (almost 40 of them) that inhabit my fireplace shrine have been gifted to me throughout the project, by other people fascinated with my obsession. Enablers, the lot of them! But I love them all. We’ve (me and all the Marys – I’m going to implicate my partner too – also an enabler) created this sorority of Marys, emancipated from expectation. They all have their own playful pet names. My favourite is Zombie Mary. She’s a holy water bottle that was rescued from a cemetery by a friend. She’s gradually disintegrated more and more over the last few years and lives in a pile of pieces at the back of the mantlepiece. Her head is carefully balanced on a shard that sticks up from her back. I love her unapologetic sinister appearance. Like, she’s in bits, but totally fine with being this existential mess. (I anthropomorphise everything.)

HCE: Your poetry covers your own life experiences and political topics like the Troubles in a raw and direct way. Is this an emotionally draining thing to do? What is the top piece of advice you would give other poets for tackling heavy/personal subjects in their writing and performance?

MB: Yes. Yes, it is. In the build-up to a show, I will have some form of meltdown; my partner is wonderful in understanding that this will happen and gives great hugs and a shoulder nook to cry into in the process. And then after the performance, the crash is woeful. I always liken it to a very intense BDSM session. There’s so much exposure that you go through, the self-care that you need to take afterwards is vital. I did three years of burlesque to learn how to direct an audience’s gaze. How to expose myself without holding that vulnerability on stage. How to pass that over to the audience and ask them to hold it for me. And I think that’s the key. You’ve got to ask the audience to make the journey with you. It’s a conversation. My first tattoo, Ginsberg’s advice ‘Follow your inner moonlight, don’t hide the madness’ was to remind me not to censor myself. I love that idea, that you say what you want to say when you don’t care who’s listening.

HCE: In your experience, is Derry a good place to be a writer/creative, and does the city have a thriving literary scene?

MB: Derry is a very queer city. I don’t mean that in an LGBTQIA+ kind of way, although we do have an incredible ‘queer’ community in that respect too. The rules that apply to other cities, don’t apply here. We march to the beat of our own drum and we always have done. We have such a strong community of artists here and whilst our lit scene ebbs and flows, we’re always working away in the background with the doing and making. There’s a great bookshop here, Little Acorns, and the owner is so passionate about supporting writers. We don’t have a literature festival, but there are a number of us pushing for it.

HCE: What type of poetry do you seek out for personal enjoyment? As a reader/listener, when you engage with a poet’s work, what are you hoping to get out of it?

MB: I am much more inclined to listen to poetry than I am to read it. That said, I will always return to Ginsberg when I’m seeking counsel. I love it when a poet uses the in-between spaces, when the unsaid is just as powerful as the said. I love listening to poets who really celebrate language as their tool. I want a poet to take me on their journey, I want to see the world through their eyes and marvel at it, like it’s my first time. If you’ve not had the chance to check out Abby Oliveira, do, she’s phenomenal.

HCE: Who or what would you say are the biggest influences on your poetry?

MB: Hmmm… Allen Ginsberg and Veronica Franco are my heroes of poetry. Both pushed the expectations and conventions of their time and I respect that rebellious nature. Ginsberg for his use of language and subject matter and Franco for being a published poet when it was unseemly for women to read. My activism has been a huge influence on my writing and how I use my platform. In terms of my actual writing, my daughter has been a huge influence, in how she sees the world or the world that I don’t want for her. She’s also my sounding board for lots of stuff. I use the relationships that I’ve had with different people, conversations that I’ve eavesdropped on, I people watch a lot and I’m very much the kind of writer that views everything as research.

HCE: What’s next on the horizon for you? Are you already working on projects/booked for upcoming performances?

MB: I am going to be doing a performance of For the Love of Mary in a small rural church in Donegal in July, potentially by candlelight as there’s no electricity, unless we find a quietish generator. It’s a fundraiser for Bród na Gaeltachta, which is Pride in the Gaeltacht area of Donegal. So that’s quite exciting and terrifying in equal amounts, as there will be native Irish speakers present. Then, it’s touring, that’s the next big thing. I made a five-year plan that ended three years ago, which was to work on improving my craft as a writer and performer, get my daughter off to uni and then tour. She went to uni and a pandemic happened. So, things got put on hold. But now I’m ready for it. I have a show that I really am proud of, that I think showcases me well as a both a writer and a performer and I really want to tour with it.

Earlier this year, I received a grant from the University of Atypical, which supports disabled artists, to create visuals for the show, so that’s my summer project, as well as reaching out and find venues that will have me…so, if anyone would love to host a very feminist show that’s about the Virgin Mary, hit me up.

If you happen to be in Derry 30th September, I will be doing the full show with visuals. Come along, it’ll be great.

HCE: What’s the best way for people to keep connected with your work or contact you for bookings?

InstagramTwitterWebsiteYouTubeApp: My Pocket Mary

HCE: Is there anything we didn’t cover that you’d like to share with our readers?

MB: I write and perform and love it. There is nothing like the feeling of applause or a standing ovation, or reading the comments in the zoom chat. To have connected with other people through my work is incredible. But I’m also frequently lost under a sea of Post-it notes in my office or running to go sit as a life model in a gallery, or tech some event. I always say that I’m incapable of boredom and that’s why I rarely sit still. So, when I do get to sneak into a Zoom room or an actual venue and listen, it’s proper nourishment for my soul. Keep doing what you’re doing folx. I’ll drop in on you every now and then, say hi, and marvel in your journeys. If that’s okay with you.