INTERVIEW: FIRE & DUST MEETS ALISON BINNEY

Now when we watch TV there’s something

making me sit upright, as if I have

a python on my head, and I try to tell if you’ve

noticed, but there’s no way of telling, you’re

sitting still too but maybe there’s something

else on your mind, maybe every time I have

a python on my head you’re worried I have

been ravaged by wolves, and I can’t tell if you’d

rather wolves or a python. Either way, there’s something.

There’s something I have to tell you.

______________________________–’Colin arrives in Albert Square’

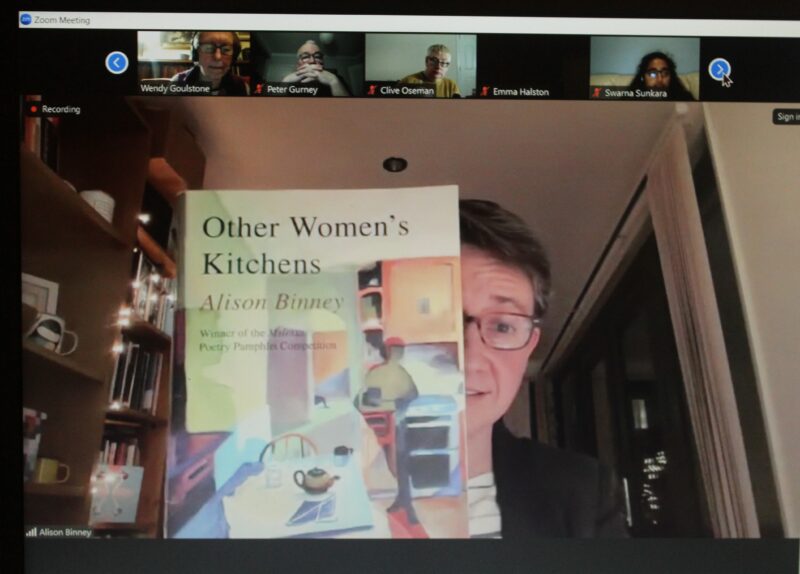

Alison Binney is a poet and English teacher based in Cambridge. In recent years, she has had poems published in The North, Magma, Under the Radar, Impossible Archetype, Brittle Star, Butcher’s Dog and Ink, Sweat and Tears. In 2019, she was longlisted in the National Poetry Competition and Highly Commended in the Bridport Prize. Alison’s debut pamphlet Other Women’s Kitchens won the Mslexia Pamphlet Competition and was published by Seren Books in September 2021. Her work was Highly Commended in the Rialto Nature and Place competition, the Plough Poetry Prize and the Ginkgo Prize for Ecopoetry across 2022, and she was the 2022 runner-up for the Mairtin Crawford Award for poets working towards a first collection. Alison also has a full collection forthcoming from Seren Books in April 2025: The Opposite of Swedish Death Cleaning.

In April 2024, Alison was the guest headliner at our virtual Fire&Dust poetry night. We’ve caught up with her since the gig, to ask a few questions…

HCE: Tell us a little about your background and journey as a writer so far. What inspired you to start creating and performing poetry?

AB: I always loved writing at school, but found that doing an English degree left me feeling completely intimidated and inhibited. About four years into my teaching career, however, I took a group of sixth formers to the Arvon Foundation at Lumb Bank, where Jackie Kay and Julia Darling were the guest tutors, and that wonderful experience really kick-started my writing again. I had some success in getting a few poems published in magazines after that, but then teaching and life took over and I stopped writing for about fifteen years. In 2016, I had a couple of months off work following surgery and a friend sent me ‘Bird by Bird’ by Anne Lamott. That book inspired me to start writing again, and also gave me some practical suggestions for getting going. It was the first time I really took my writing seriously as an adult, and a year later I reduced my teaching hours to 80% in order to have a whole day for writing every week. Even if I’m not writing poems on that day, there’s a lot of poetry admin to do, and it’s also given me more space for doing readings and workshops, which I love doing. Winning the Mslexia Pamphlet Competition in 2021 gave me a huge boost, and has led not only to more poetry events, but also to the publication of my full-length collection in spring 2025.

HCE: Your pamphlet is a debut both powerful and understated; it seems to highlight some of the pains experienced by many people in LGBTQ+ communities, playfully making use of subverted expectations and raw data to expose stereotypes and prejudice, while also celebrating joyful moments, love, progress and self-discovery.

What have responses to the book been like? Have readers connected with the material in ways you hoped they would, and do you have an ideal audience in mind when you’re putting a poem together?

AB: I try not to have a particular audience in mind when I’m writing because I worry that that might get in the way of a poem going where it needs to go. But I do very much want my poems to be read when they’re ready, and there’s no better feeling than knowing that a particular poem has resonated with someone. Of all the poems in ‘Other Women’s Kitchens’, ‘Haircut, 17’ is the one that seems to have resonated the most, particularly with other lesbians. And ‘Colin Arrives in Albert Square’ is another one that people often mention. I think even if you’re not gay, people recognise that uncomfortable feeling of watching TV with a parent when a sex scene comes on, for example, so that’s what people relate to in that poem.

HCE: Several of the poems you shared at Fire&Dust explored the idea of people not being able to live as their authentic selves. Are there other themes or motifs that you tend to gravitate to in your work?

AB: I wasn’t conscious of this until I assembled the poems in my new collection, but a lot of my poems seem to be about connection – connections between people, between people and the natural world, between people and objects etc.

In terms of people – particularly women – not being able to live as their authentic selves, having written a pamphlet (Other Women’s Kitchens) which felt quite personal to me, I’m really appreciating now working on what I secretly call my ‘dead lesbians’ poems, which explore the lives of women who lived hundreds of years ago. It’s refreshing to take myself out of these poems completely, whilst still working on a theme that resonates with my experiences.

HCE: Who or what would you say are the biggest influences on your writing?

AB: Without Anne Lamott’s ‘Bird by Bird’, I’m not sure I’d have started writing again at all. It’s a brilliant book, and one that I often return to for advice. In terms of poetry, I love Carol Ann Duffy’s poems, both as a reader and as a teacher. I admire the way she uses precise, personal details in ways that also resonate with the reader. I think also just reading lots of contemporary poetry – subscribing to magazines like ‘The Rialto’, ‘Butcher’s Dog’ and ‘Magma’ – which allows lots of different writers and styles to influence me.

HCE: One of the poems you read at Fire&Dust had been inspired by reuniting with a familiar piece of Tupperware when clearing out your father’s house. Others include a found poem using titles of online articles and ‘listicles’, private fears during a haircut and the first gay character to appear on Eastenders. Do you find that deeper/subtextual meanings and messages resonate better with readers when the poetry emerges from everyday objects and encounters?

AB: Yes, definitely. That’s where many of my poems begin, and often I just feel as if an object or encounter wants to be written about without knowing where the poem is going to take me. That was certainly the case with the poem about the Tupperware party Susan. It’s then a question of staying with the object or encounter, listening carefully to it, noting whether the energy around it wants to go, and following that.

Also, I think the process of sorting and clearing my parents’ house, which entailed getting rid of a huge amount of stuff, motivated me to capture particular objects in poetry as a way of keeping hold of them.

HCE: Some of your poetry explores uncomfortable experiences in a raw and honest way – is it emotionally draining to then re-engage with this vulnerability when you give readings? What is the top piece of advice you would give other poets for tackling heavy/personal topics in their writing?

AB: That’s a really good question. Honestly, I don’t find reading poems in public emotionally draining, even when they deal rawly and honestly with uncomfortable experiences. Perhaps that’s because I find the process of writing about such experiences quite therapeutic. It forces me to stay with a particular experience for a long time in order to draft and re-draft the poem, by which time it feels as if the poem safely contains the feelings in such a way that I can read it aloud in public. I also wonder whether reading in public is very similar to teaching, in that in both situations there’s a strong fear of exposure. So much of teaching is about performance – you have to bring an authentic enthusiasm to the classroom, while at the same time adopting a protective persona. I think the same applies to poetry readings.

HCE: Many of us have negative memories of encountering poetry in the classroom, as it’s often taught in a manner that frustrates kids and provokes a life-long repulsion. As an English teacher, do you find there are specific challenges to getting young people interested in reading (and writing) poems?

AB: I love teaching poetry – both reading and writing. Small children have a natural enthusiasm for it (I remember my nephew echoing the intonation of Julia Donaldson’s ‘The Snail and the Whale’ while he was still too young to pronounce all the words), and I feel it’s my job as a secondary school English teacher to help young people to tune back into that sense of what a poem can do and be. I don’t think people grow out of a relish for rhythm, rhyme, word-play, story-telling or riddles, although they might have experienced some poetry teaching which has left them feeling as if poetry is inaccessible or boring for them. Teaching poetry, then, is about helping students to tune back in to that sense of relish and connection, and encouraging them to develop the resilience to stay with a poem that might seem opaque at first, but which might, after some exploration, yield something which resonates with them.

When I’m writing poems I have the voice of an imaginary Year 11 student in my head saying, ‘I don’t get it.’ I think sometimes that can lead me to over-explain things in my own poems – like my Year 11s, I don’t like poems that make me feel stupid – but I’m trying to learn to trust the reader more. Similarly, in my teaching, it can be quite satisfying to hear students saying, ‘I don’t get it’ on a first encounter with a new poem, and then, by the end of the lesson, to listen to them expressing views and emotions in response to that same poem, once they’ve spent a bit of time with it.

But I don’t think many people come to love a poem by their teacher projecting it on the board and annotating it in front of the class, which is what poetry teaching looks like in some classrooms, so the creative challenge is to find approaches like using collages, discussion, story-telling, soundscapes, choral readings, video clips and word games to help students to encounter poems in more playful and authentic ways.

HCE: What elements, in your opinion, do most well-written poems have in common?

AB: Authenticity. Precision. An ear for language. Lack of pretension.

HCE: What more should arts communities be doing to support LGBTQ+ poets, to make sure their voices are platformed and heard?

AB: Diversity of all kinds is essential for the richness of any arts community, so it’s great that you’re asking that question. But it’s that very acronym – ‘LGBTQ+’ – that I think is becoming increasingly unhelpful, and that currently risks squeezing out some important voices. I recently heard a student, who was discussing ‘The Ballad of Reading Gaol’, describe Oscar Wilde as ‘a member of the LGBTQ+ community’, and it sounded so jarring. Oscar Wilde wasn’t imprisoned for being ‘a member of the LGBTQ+ community’ – he was gaoled because he was a homosexual man. His lesbian contemporaries might have had a tough time in other ways, but they weren’t criminalised. There are many other examples of where the acronym ‘LGBTQ+’ has been rather blandly applied in ways that gloss over the fact that it encompasses an increasingly wide range of people with hugely different needs, perspectives and priorities. That’s obvious when you consider just a few of the people who might be included under that umbrella: a young asexual non-binary person; a gay man who was criminalised when he first came out, and who survived the AIDS pandemic; a transgender heterosexual couple trying to conceive; and a woman whose heritage is in the lesbian separatist movement of the 1970s, during which time she lost custody of her children. The particular issues faced by each of these people are hugely different; their perspectives will all have been shaped by such contrasting experiences. All of their voices deserve to be heard, and I would like arts communities to show greater attentiveness to those whose voices are often not heard as loudly – which should include the growing number of often middle-aged and older lesbians and gay men who find the acronym ‘LGBTQ+’ an uncomfortable fit and who may now position themselves at some distance from it. And I would like to see arts communities showing greater courage in acknowledging where genuine tensions and differences of perspective exist.

I was recently on the point of submitting some poems to a particular press when I saw a statement in their submissions guidelines to the effect that if the editors found that any poets whom they had published had been homophobic, transphobic or racist, they would publicly denounce them and also report them to all the other publishers and arts communities they knew. It stopped me from submitting my work to them. I find this sort of puritanical zeal chilling and I want nothing to do with it. One of the most uplifting experiences of my life was seeing the progress made towards gay equality through the 1990s and 2000s, which came about as a result of creative, compassionate and diligent campaigning on a range of fronts. It wasn’t achieved through shaming people, but through engaging them in discussion and debate. You don’t win hearts and minds by silencing people and making them anxious. So I’d like to see arts communities being braver and more creative, offering playful spaces for a diverse range of people to take part, take risks, take offence, take stock, take account.

HCE: You mentioned at Fire&Dust how Zoom gigs tend to feel even more intimate than in-venue gigs, due to how faces are on display and people can share comments during the readings. During the UK lockdowns, were there things you missed about in-venue events?

AB: Yes! I missed that poetry appreciation noise that an audience often makes at the end of a poem. It’s a special sort of collective ‘Aaah’ sound, that you don’t hear anywhere else. I missed hearing it, and I missed participating in it. It’s not possible to achieve it on Zoom. I also missed the slightly warm glasses of wine and the random conversations. And it’s hard to achieve quite the same buzz of connection when you’re online. It’s the same with teaching – it’s so much more satisfying in person, even though we discovered wonderful new ways of doing things online in the pandemic.

HCE: How are you finding the experience of creating your second book, compared to putting together Other Women’s Kitchens? Are you able to give our readers a little insight into the premise of the new book?

AB: My new collection is called The Opposite of Swedish Death Cleaning. I wrote the title poem while sorting and clearing my parents’ house after my dad was admitted to a care home. Swedish death cleaning has become quite popular in recent years, and is a term for the practice of decluttering one’s own life, often in late middle age, in order to save others work after you die. It’s a great idea in theory, and when I started clearing Dad’s house I really wished someone had introduced him to the concept twenty years earlier! I realised that what I was doing in his house was the exact opposite – I was doing it for him, he wasn’t dead, we’re not Swedish, and it was not a very clean process.

However, I also came to see Swedish death cleaning as a stark, clinical practice, which in the end I was glad my dad hadn’t embraced. The experience of spending so much time in his house with all the familiar and surprising things I discovered there was very precious to me.

The Opposite of Swedish Death Cleaning is bookended by sequences of poems that explore both the emotional and practical challenges of caring for a parent with dementia. In between, there are poems about love, plants, birds, food, walks, but I think what binds the whole collection is a search for connection. It’s much harder to assemble a collection than a pamphlet because it’s typically three times as long, and the poems tend to cover a broader range of themes. One practical challenge is that you quickly run out of floor when you spread the poems out to try to work on the sequencing! But another challenge is trying to listen to what the poems are saying when they are assembled and in conversation with one another. It took me a while to see these sixty-odd poems as a coherent collection, but that’s where the editors at Seren Books were particularly helpful. By suggesting some changes to the first and final poems, suddenly the whole collection hung together much better. I was too close to the collection to make that change for myself, so their input was invaluable.

HCE: Besides your upcoming first full collection, what’s next on the horizon for you?

AB: My next project after that is a sequence of poems which tell the stories of women from the past who may have had, or sought, intimate relationships with other women. I hesitate to use the word ‘lesbian’ because it feels anachronistic when discussing women who may never even have heard of that term, and/or who might have felt uncomfortable applying it to themselves. But these are women who were in close relationships with other women, and who often lived lives that didn’t conform to gender stereotypes of the time. So far I’ve written about a pair of female pirates, some fifteenth century brass rubbings, a woman tried as a witch, a heartbroken Victorian gardener and the legendary footballer Lily Parr. I’m loving the challenge of discovering women from history whom I have never heard of, and listening to where the poems about them want to go. Sadly, so many women’s stories have never been recorded, and where there are records, it is usually for tragic reasons: several of these women were blackmailed, tried or imprisoned so we know of them through court reports. But I want to celebrate these women as well as honouring their stories, so in each case I’m trying to make a sound judgement about which bits of their story to focus on. It’s a fascinating process and, if nothing else, I’m very glad to know now of so many women whose names I had never heard of before.

HCE: What’s the best way for people to keep connected with you and your work, or contact you for bookings?

HCE: Is there anything we didn’t cover that you’d like to share with our readers?

AB: I don’t think so, but thanks so much for the interview. These were great questions and I really enjoyed answering them.

Alison’s collection Other Women’s Kitchens is currently out of stock at Seren Books but available online from the Poetry Book Society and other retailers.