Asian Mythology: Gods and Monsters

By Eve Volungeviciute

The time has come for another mythology-themed article! This time, we are travelling to the East, all the way to Asia. Their many regions, each with their different folklore and beliefs, have a lot to offer us with regards to learning new things about various cultures. Anyway, enough of my chit chat – let’s dive in!

Caucasus

Armenian

Armenian mythology takes inspiration from multiple different beliefs, such as Roman and Greek. Their oldest cults worshipped Ar, a creator that was imagined as the sun, which led to ancient Armenians calling themselves ‘children of the sun’. Eagles and lions were also worshiped.

Ancient Armenian deities are kind of counter paths to Greek gods; for example, Aramazd is a counter path for Zeus, Vahagn for Heracles, and so on. There’s a fair share of monstrous creatures as well, such as Al, a dwarfish evil spirit who kidnaps babies and attacks pregnant women, bearing appearance of a half human/half animal, with iron teeth and copper nails. And it can also become invisible! There’s also Nhang, shape-shifter serpent monster who could transform into a woman, lure men into the water, drown them and drink their blood.

After Armenians adopted Christianity in the fourth century, Christian beliefs were integrated into the Armenian folklore, leading to Biblical personalities taking over for the Archaic gods and spirits.

Central

Scythian

Scythians focus a lot on the archaeological aspect of their culture, especially chariot burials. The stag is also common in their artwork, being quite prominent at funeral sites. As Herodotus states, the Scythians worshipped a pantheon of seven gods and goddesses, which are quite similar to Greek entities in nature. The structure of the pantheon was also divided into three ranks.

The Enarei, a clergy formed by transvestive priests, are also an important part of Synthian religion. They were also involved in a cult of Artimpasa, which was influenced by Near Eastern fertility goddesses. The androgyny of Enarei was also described as a female disease which caused sexual impotency, inflicted by Artimpasa as punishment.

East

Japanese

Japanese

Japan had many ways of passing down their beliefs, such as oral traditions or literary and archaeological sources. Taking into account the fact that Japanese communities have been quite isolated throughout the country’s history, each region ended up having their own tales and legends specific to that particular geographic location.

Two most referenced and oldest sources of Japanese history and folklore are the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki, written in the eighth century and discussing the mythic origins of the Japanese archipelago and its people. This history is separated into three eras – the Jomun, Yayoi and Kofun periods, divided by different archaeological discoveries.

Japan’s creation narrative is usually considered to be in two parts – the birth of the deities ‘Kamiumi’ and the birth of the land ‘Kuniumi’. As the name suggests, the birth of the deities refers to the first generation of gods. The Japanese also have their own origin story for the Sun and the Moon which they tell through the myth of Izanagi’s return from Yomi.

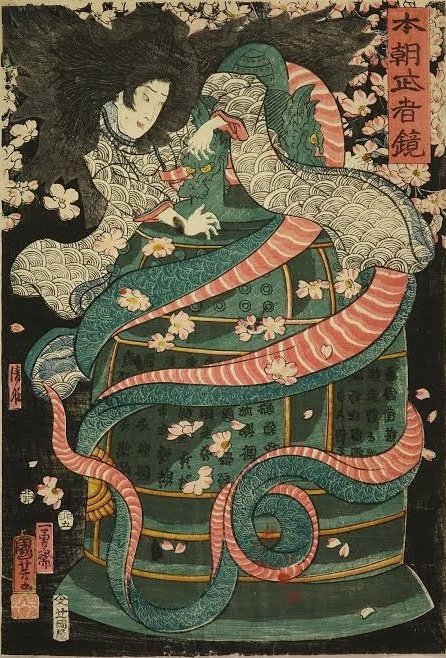

There are at least eight million Japanese gods, mostly descendants from the original trio gods born from nothing. They also have their fair share of not so nice entities. A few of them would include Kiyohime, a scorned lover who transforms into a serpent in order to get her revenge, or Yuki-onna, a ghost who appears during snowfall and feeds on human essence. Yama Uba, the mountain ogress, is a marginalised old woman living in the mountains as the name suggests, while also having a taste for human flesh.

Korean

Korean mythology is comprised of two categories – literary mythology, which is so wrapped up in the country’s history that it’s quite difficult to differentiate between myth and actual facts, and corpus oral mythology, which a lot of people regard as being richer in material than the literary option.

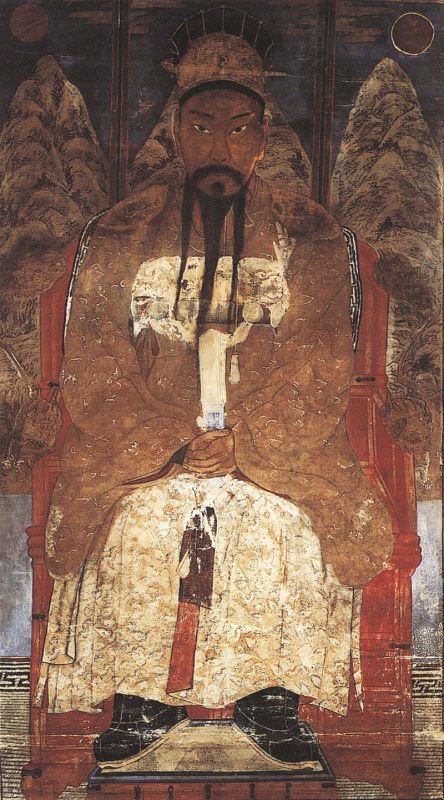

State foundation myths centre on the subject of Korean’s first ruler, from his supernatural birth, the ruling of his kingdom, to his death. The oldest surviving texts of the founding myths of ancient Korean kingdoms are transcribed in Classical Chinese. The earliest kingdom is Gojoseon, its creation myth being that Hwahung, the son of the sky god Hwanin wants to go to Earth and rule it. He descends to the planet beneath a sacred tree on Mount Taebaek where he and his followers found the what is called ‘the Sacred City’.

Korean creatures also have shapeshifting qualities, such as Gumiho, half-fox, half-human who seduces men and women alike, or Gwishin, which is more or less a distant relative of western ghosts and has been popularised in Korean and Japanese horror films (‘The Ring’ definitely springs to mind).

A huge part of Korean culture and religion are shamanic myths. During the time when the shamanic ideologies were frowned upon, women were marginalised as the practice was associated with them. Due to this, shamanism is considered a subversion of Korean mythology and beliefs.

South

Romani

Romani were one of those cultures who did not have a set habitat region, which led to most of them migrating to Europe. It was widely believed that certain Romani had passive psychic powers like empathy or precognition. Some legends even mention astral projection or telepathy.

A few of their folk tales include ‘The Creation of the Violin’, which tells a story about a couple who cannot have a child, which causes the wife to listen to an old woman’s magical advice in order to have an offspring. The woman dies shortly after birth, leaving her son to grow up motherless. As an adult, the son travels to a kingdom where the king promises his daughter to a man who can ‘do something which has not been done in the world before’. With the help of the magic fairy who lets him pluck some of her hair, as well as giving him a box and a rod, thus creating a violin.

Another example of a tale would be ‘The King of England and Three Sons’, which draws on common fairy tale tropes of princesses, hero journeys, magical objects and shapeshifters.

Indonesian

Most Indonesian ethnic groups explain the origins of the universe and their gods and deities through creation myths. Ancient people in Java and Bali believed in Hyangs – a spiritual entity with supernatural powers.

As some ethnic groups in Sulawesi state, the earth sat upon the back of gigantic babirusa. When the boar rubbed its itchy back against a palm tree, an earthquake happened. The myth is repeated in other nations, such as Varaha and Vishnu, showing similar patterns throughout different cultures.

Indonesians do not lack their own deities and creatures. For example, Buto Ijo – green trolls that kidnap children – or Cindaku, which are similar to werewolves.

West

Kurdish

In Kurdish mythology, there is an origin story in which the ancestors of the Kurds fled to the mountains to escape the oppression of their king Zahnak. To this day, mountains remain essential figures in Kurdish culture.

Shahmaran is a mythical creature in Kurdish lore, a snake-human hybrid who was considered a wisdom goddess. It was believed that after Shahmaran’s death, her spirit is passed on to her daughter.

Persian

Morality in Persian myths is quite black and white, all deities and creatures being either good or evil. The world was thought to be in a battle between Ahriman and his demonic dews and Ormuzd, the creator.

As in many other nations, snakes were considered a symbol of evil in Persian folklore, whereas birds were usually a good omen. Peri were ‘beautiful but evil’ winged members of a mythological army who gradually became represented less as evil and, in turn, more benevolent and beautiful creatures, to the point of becoming a symbol of beauty in the culture.

Some recommended reading for people who wish to explore these topics further:

Asian Mythology. Myths and Legends of China, Japan, Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia by Rachel Storm

Myths and Legends of Japan by F. Hadland-Davis

Fiction:

The Library of Fates by Aditi Khorana

Shadow of The Fox by Julie Kagawa

A Thousand Beginnings and Endings anthology edited by Ellen Oh and Elsie Chapman