REVIEW: ANTONY OWEN’S ‘THE UNKNOWN CIVILIAN’

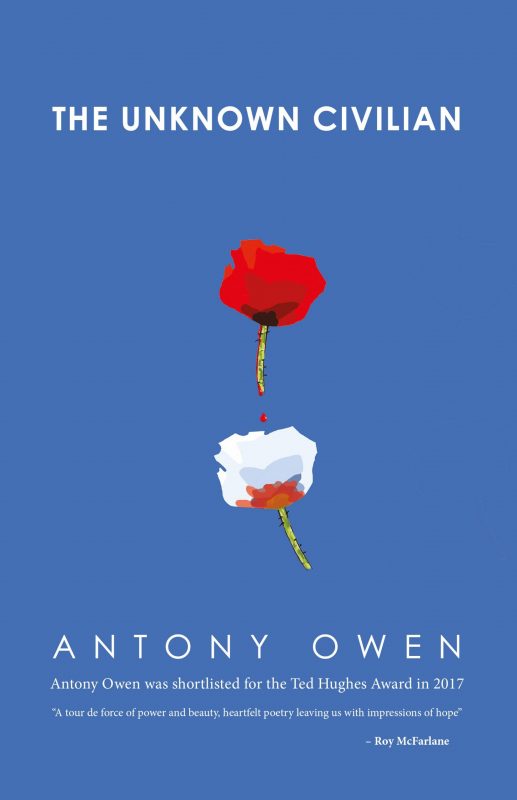

THE UNKNOWN CIVILIAN BY ANTONY OWEN

Knives Forks and Spoons Press

ISBN: 978-1-912211-49-4

£18.00/115 pages

Reviewed by Fergus McGonigal

“My hardest battle is tending to a wound that keeps reappearing” writes Owen in the opening poem of his latest collection, The Unknown Civilian (KFS Press, 2020). The title of the poem provides a context (‘A Black Nurse Tends to Wounds’), but if you have followed Owen’s output over the last decade, you might imagine that he is referring to the task of writing about what has been his greatest preoccupation: human armed conflict and its many shadows. In both The Dreaded Boy (Pighog Press, 2011) and the Ted Hughes Award nominated The Nagasaki Elder (V Press, 2017), broadly speaking, he wrote respectively about recent conflicts, and the devastating impacts of the use of atomic and nuclear weapons. The scope of The Unknown Civilian reaches further: armed conflict over the last century. While the general scope of the subject may be broader, Owen continues to paint with the finest of brushes and has managed, once again, to tackle subjects which most of us would turn away from – the terminal violence, horror, anguish, despair and madness inherent in war and all of its terrible consequences – and does so with beauty and humanity. That he repeatedly finds poetry in these, the darkest places, is a testament to his remarkable dexterity, imagination and compassion.

“My hardest battle is tending to a wound that keeps reappearing” writes Owen in the opening poem of his latest collection, The Unknown Civilian (KFS Press, 2020). The title of the poem provides a context (‘A Black Nurse Tends to Wounds’), but if you have followed Owen’s output over the last decade, you might imagine that he is referring to the task of writing about what has been his greatest preoccupation: human armed conflict and its many shadows. In both The Dreaded Boy (Pighog Press, 2011) and the Ted Hughes Award nominated The Nagasaki Elder (V Press, 2017), broadly speaking, he wrote respectively about recent conflicts, and the devastating impacts of the use of atomic and nuclear weapons. The scope of The Unknown Civilian reaches further: armed conflict over the last century. While the general scope of the subject may be broader, Owen continues to paint with the finest of brushes and has managed, once again, to tackle subjects which most of us would turn away from – the terminal violence, horror, anguish, despair and madness inherent in war and all of its terrible consequences – and does so with beauty and humanity. That he repeatedly finds poetry in these, the darkest places, is a testament to his remarkable dexterity, imagination and compassion.

The book itself is a long one for a poetry collection (over a hundred pages, divided into seven sections, and containing 81 poems); but despite this, and the high emotional impact of the poems, I found the reading and re-reading of it compelling. A clumsier poet, and a less skilful editor, could have created an impenetrable tome, but what I see is deftness aplenty. ‘”Let’s do this properly and write war poems with etiquette” he says with magnificent irony in ‘The Last Minute of Wilfred Owen’s Life’. It sets the tone for what is to follow: war poems, properly written, but without etiquette. “…something in Latin to dress death elegantly”? Not here. By the end of the first section, I already found myself saying, ‘What a piece of work is man…’ This brief section concerns World War I, and by the end of its final poem, ‘Animals and Monsters in Men’, I was pondering on whether the truth Owen seeks in dissecting war holds for all wars; “…people come back in the flesh but not so in the eyes” he writes; and the statistics about homelessness and suicide for veterans of modern-day conflicts suggests that it does.

By the end of Part II, it struck me that Owen’s approach is the right way to commemorate the dead: not with grandeur and solemnity, but with poems which strike you as being like hymns and songs and prayers for the dead and the maimed. “Men never look happy as soldiers: they strut into instructed death” (‘The Sikh Soldier’). If we are honest in our loftily stated intent of ‘never shall we forget’, it would make sense to read such lines from the pulpit and at the war memorials on Remembrance Sunday. “Show me all the things I know are too evil” he writes in ‘Lidice’. The line should be rung like a church bell; or instead of. He may be writing about a different place and a different time, but such lines have Owen holding up a mirror to contemporary conflict. Here’s a suggestion: read this book, or at least the last three sections, and then watch the news for a week.

A great achievement of this collection is to be both deeply and densely poetic, and yet immediately accessible. One of the ways Owen does this is to engage us through the element of story-telling, which inhabits many of the poems, alongside the touches of light he uses to cast the shadows of Hell: “In the square, they are beating men to classical music” (‘Song for a Yellow Star Belt’). He goes beyond himself to find a collective voice (you’ll find no ‘I-strain’ here), and when we do meet the first-person, it is a pilot or a soldier or a nurse. We have a poet who is making poets of the dead. “I have dishonoured the wind with my blade” says the imagined pilot in Love Letter from a Kamikaze Pilot. These feats of poetic imagination work because Owen allows these characters to speak for themselves; so we see an imagined world narrated by the nurse, the Kamikaze pilot, the German soldier at Stalingrad, and so on. Like the tanks which no longer swerve to avoid bodies, Owen does not let these characters swerve to avoid truth.

I don’t know about you, but when I read poetry, I look for images which trip me up, and this collection is generous with such moments. Mind you, this is sometimes a case of ‘be careful what you wish for’: ‘Where Widows Wash in Hiroshima’ tripped me up with the image of nursing mothers “teasing out pus with lavender oil, hoping for milk”. Like the men being beaten to the strains of classical music, it is the juxtaposition of beauty and ugliness which magnifies and amplifies the horror. I found it very effective. And disturbing. Here’s a caveat: Owen stays true to writing poems which lack in ‘etiquette’ throughout the book. But isn’t that precisely what is needed in such a collection?

Another startling juxtaposition is the juxtaposition of civvy street, or home, “when people fought over Miley Cyrus and if she’d gone too far” (‘Valentine’s Day for Invisible People’) and the ‘out there’ of the war zone. It’s an important and significant mismatch. Siegfried Sassoon wrote about the same jarring disconnection between the vacuous banality of entertainments and preoccupations at home and the catastrophe of ‘out there’ over a hundred years ago in ‘Blighters’, and by the midway point of this collection, hitting this particular nerve had me thinking that it seems as though we have learned little or even nothing in the intervening period. This feeling was compounded in Part IV, when I heard the echo of (Wilfred) Owen’s ‘I am the enemy you killed, my friend…’ in ‘A German Soldier in Russian Boots’: “Comrade, the motherland is full of brothers in arms”. Soldiers fighting for opposing armies, having first met on the battlefield, all too often find themselves meeting the same end – a brutal death in Hell, or, and here’s the thing: in Syria or Yemen or Rohingya or Guam or Palestine or Gaza or Baghdad or Sarajevo, all of which find prominence in here. But it’s not just the soldiers in these places, is it? It’s the defenceless men, women and children (who find themselves in Hell); those who give weight to the title: the unknown civilians whom Owen is trying to make known to us throughout much of the final sections. And, crucially, there’s no juxtaposition between home and ‘out there’. Home is ‘out there’. Right now.

Meanwhile, “A poet in Oxford is writing a poem about the smell in Wordsworth’s cottage” (‘Dead Babies Stolen for Nuclear Tests’).

In reading the poems of The Unknown Civilian, we inhabit so many conflicts it seems as if all conflict is here within these pages: not the vague sense of mindless loss of the Lost Generation from WWI, which are so often evoked on Remembrance Sunday, but all of the bloody conflicts of the last 100 years since its end, from WWI to Syria, via Rwanda, Belfast, Syria, The Falklands, et al. Towards the end of this collection, I worried that its author might perhaps have given something of himself away when he wrote of children “with eyes drunk on darkness” (‘Stalingrad’). Given the subject matter, it seems jarring to label his efforts as courageous, but they are, albeit of a different kind of courage, because the subjects here are so relentlessly, numbingly dark yet he has engaged with this darkness, repeatedly, to find profound poetic responses. Having finished the collection, I recalled a phrase, ‘deluded peacenik that I am’, which I had written in one of my poems several years ago. It made me ask myself this: what is the point of being a deluded peacenik (apart from getting a laugh in a surreal, comic poem) and where do I go from here? Owen has a suggestion: “Help them” he simply states at the ‘random’ end of ‘The Unfashionable Death of Another Syrian Daughter’. I’m not sure how I do this, except perhaps to make a start by recommending this book to you; not only will it nudge your consciousness and awareness, but it contains poetry of the highest calibre.

The Unknown Civilian is available online from KFS Press. Antony’s latest collection Cov Kids (2021) is now also available online from KFS Press.