REVIEW: SUNDRA LAWRENCE’S ‘WARRIORS’

Reviewed by Stella Backhouse

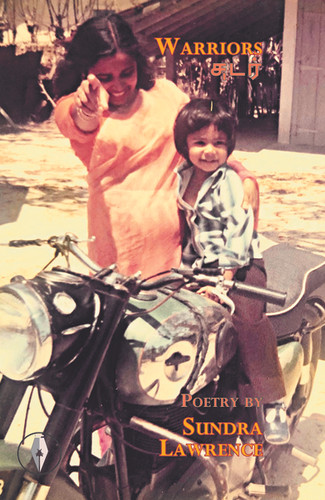

Sundra Lawrence packs a lot into her Aryamati Poetry Prize 2021-winning pamphlet Warriors, newly published by Fly on the Wall Press. Although the poems cover just twenty brief pages, still the collection bears the imprint of three different sections, carefully threaded together by recurring themes of division and unification on both personal and political levels. And while its immediate background is the Sri Lankan Civil War of 1983-2009, beyond that it is also informed by the dual legacies of colonialism and conflict, and the experience of diaspora and cultural shift that is secondary to both.

A child of that diaspora herself, Lawrence was born and raised in London, in a Sri Lankan Tamil Roman Catholic family. The collection’s opening poems address the Sri Lankan Civil War, but seen from a distance and through the eyes of children. Lawrence and her brother’s experience of Sri Lanka is through its food – the hot rasam soup cooked by their mother to dry their colds – its music, and random household oddments such as the herbal ointment Tiger Balm, which childhood logic and word-associations somehow connect to Tamil Tiger bombs.

Lawrence does a good job of conveying the displacement of the Sri Lankan Tamil community and the unfocused, flickering presence of the war. In the kitchen, clammy tensions threaten to boil over when “The swell of heat claps the pot lid/and sweats our yellow wall” but the served soup is safely enclosed in bowls balanced on the children’s laps. In the slightly unlikely setting of Normandy, the family enjoys a holiday picnic with relatives living in France: “the mums talk Tamil. I listen to its song/chew straw, suck the memory of orange.” The dads dance to Sri Lankan baila music, a colonial import from Africa re-branded with a European name; something that has also passed through many cultures, embedding their memories along its way: “The music of Mozambique slaves, who were/shipped by the Portuguese to fight Lankan kings”.

The second group of poems views the war at closer range, including a terrifying episode experienced by Lawrence’s own family during a visit to Sri Lanka in 1995. On their way home after a night out in Colombo, they are stopped at a check-point and questioned by armed Sinhalese officers. But in a more-that-unites-us-than-divides-us moment, the situation is resolved when Lawrence’s mother and the guard realise they grew up in the same neighbourhood. Suddenly “his voice/ is song, neighbourhood song and when did she leave?”

The other poems in this section are angrier, detailing atrocities of war including the brutal murder of Tamil leader Kuttimani in the Welikada Prison Riot of 1983, an outrage also recounted in Anuk Arudpragasam’s 2021 Booker Prize-shortlisted novel A Passage North. Special fury is reserved for a description of the cultural desecration represented by the razing of the Jaffna Public Library, “your 100,000 books burnt to black pollen./Eyewitnesses see police start the fire”. But although the lines “In the diaspora, spines of Tamil books stand unbent/like the tongues of second generation, eyes illiterate to the swirl of letters”, the use of the word “pollen” also hints at the possibility of cross-fertilisation and cultural renewal, perhaps in unexpected and far-flung places.

The last poems return to the personal with the age-old story of love across the divide despite family disapproval on both sides. At Lawrence’s home “The net curtain twitched like it wasn’t watching./I lipsticked my number in the back of your A-Z./I knew she was ready to drag me out of the car.” Meanwhile at her Jewish boyfriend’s house “Your mother cried when you brought/my name home for dinner one Friday night.” Thankfully, this Romeo and Juliet have a happy ending, with the couple “together for seventeen, married/for ten years, anchor your iris to mine”.

Though short, this collection has a lot to say about cultural interconnectedness, shared pasts and human unity. It does not forget the hurts of history or the importance of preserving identity, for example when an admirably uncowed Lawrence tells the rabbis who question her before her marriage “this is not a conversion. It is an extension/into your world”; but it presents an ultimately optimistic vision of our abilities to synthesize our different heritages and forge new selves.

Warriors is available online direct from publisher Fly on the Wall Press, as well as other bookshops and retailers.