INTERVIEW: FIRE & DUST MEETS PETER RAYNARD

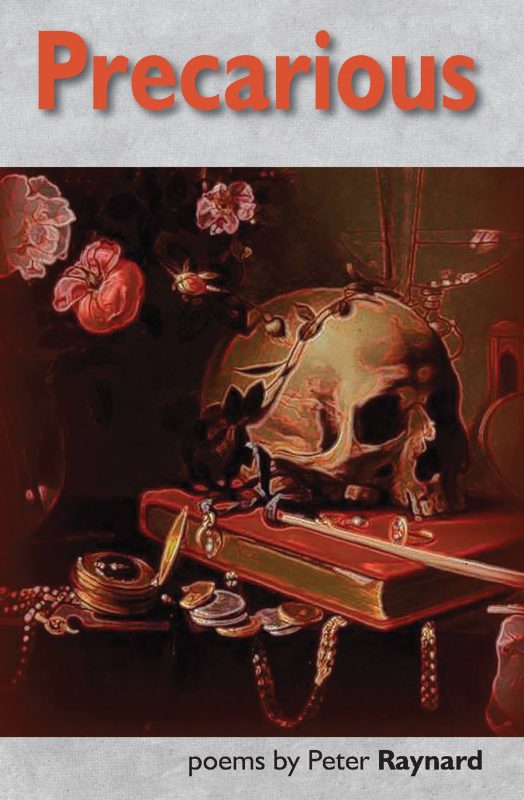

PRECARIOUS BY PETER RAYNARD

Smokestack Books

ISBN 978-0-9957675-9-1

£7.99/95 pages

“Young Timmy knows how to enjoy himself,

he cleans double breasted windows,

or checks under the sink for some

scantily clad plumbing, before delivering

a whipped cream double entendre

to bored housewives. Rita likes a bit

of that an’ all, off shagging Bob,

with her mate Sue, but her namesake

tries her hand at books instead of dotting

her luck on the bingo of a Saturday night.

Shirley’s fucked off to Greece, can’t stand

talking to the wall no more, cooking

egg ‘n chips for her husband,

who believes that’s a woman’s place.

Billy’s dad knows what a man should be,

and it’s not a fucking dancer […]”

____________________excerpt from ‘If we were real’

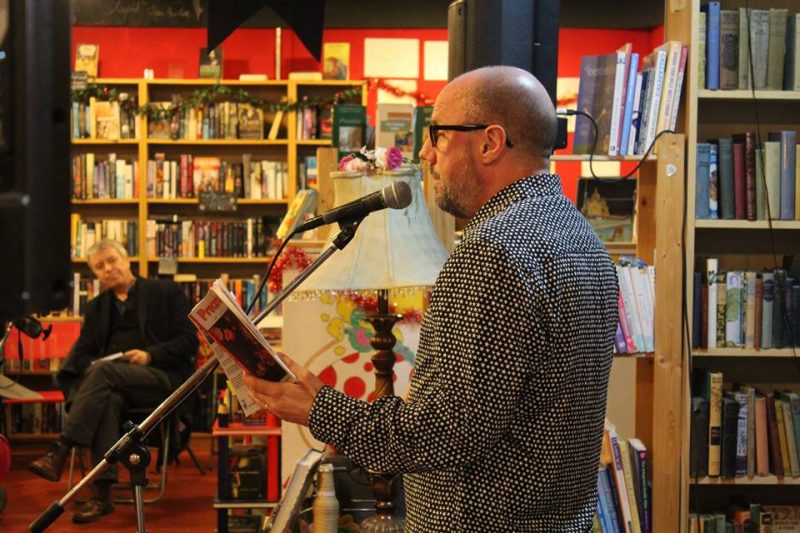

Peter Raynard is editor of Proletarian Poetry: poems of working class lives. He is the author of two books of poetry: Precarious (Smokestack, 2018), his debut collection, and The Combination: a poetic coupling of the Communist Manifesto (Culture Matters, 2018). In December, Peter headlined at our Fire & Dust poetry night, alongside Jane Commane.

We caught up with him after the gig, to ask a few questions…

When did you first know you were a poet; what inspired you to start?

A poetry module with Malika Booker, as part of my creative writing M.A., inspired me to start. Poets such as Sharon Olds, Inua Ellams, Jacob Sam La Rose, William Blake, Gwendolyn Brooks, and Anna Robinson, showed me a different perspective about poetry. I didn’t consider myself a poet until I had been published and I was only writing in that form. However, neither is the sole definition of a poet. Certainly, writing in other genres, which I do to some extent now, can only strengthen your poetry. And as for being published, yes it’s great but I enjoy the act of writing much more than seeing my work in a magazine or book.

Who is your work aimed at – do you have an audience in mind when you’re creating a poem?

I don’t have an audience as such, but I do have my friends from Coventry on my shoulder. Like many people, poetry was not even on my radar, not even when I began writing ‘creatively’. So now it is front & centre, I feel a responsibility to make sure it relates to people who have been put off by a perception of poetry, imbued at school, that it is for and by ‘other’ people. And they’re not wrong in the predominance of mainstream poetry – done by and for the middle classes.

What do you see as the main themes in your work, and was there a particular message you hoped readers would take from your collection Precarious?

Main themes are class, politics, masculinity, and mental health. The class and politics focus on portrayals of the working class; trying to overcome the negative and/or patronising portrayals that see our ‘plight’ as something to escape from or endure. Regarding masculinity and mental health, my focus is on their inter-relationship, and the fact that men don’t really speak about their mental health, and the fact that seven of them kill themselves each day in the UK.

The title of the collection felt relevant for every poem – but we’re curious: does it refer to something specific?

I thought a lot about the title. I grew up in the sixties and seventies, and although there were political ruptures, working class people had a job for life, could own their own house, go on holidays, etc. Now, no-one, except a certain elite, has that security. We live in precarious times, which is compounded by the absolute uncertainty about the future.

Your poetry is straight-talking but consistently features standout imagery and well-crafted language. Talk us through your writing process. (For instance, do the images come first and you build the poem up around them?)

A good question is always one that is difficult to answer, and this is one of them. Thank you very much for your compliment – when I first started I wasn’t confident at all in ‘straight-talking’, as I had a different impression what poetry was from what it could be. The poets Malika Booker (my original teacher) and Jo Bell (my mentor early on), changed that perception completely.

As to my writing process: I try to write every day, and poetry is great for that – you can pick up from where you left off on a poem, or just start another. It’s much more practical, I feel, than say writing a novel (although I am currently trying to write a verse novel). I feel this way I guess, as I like to come away from writing feeling like I have achieved something, even if it is just say a paragraph, or rough draft.

I tend to build poems around an idea as opposed to an image. For example, I want to write a poem about the Consumer Price Index, where each product is a person with the cultural bias. Food in particular is a great hunting ground for writing about class. Writing my blog Proletarian Poetry is great for that. as I enjoy the research behind it then writing a few hundred words introduction to the poem.

It’s clear from poems like If We Were Real that you feel representation of working-class characters in literature has a long way to go. Do you think there’s been any recent progress made in this respect; are enough working-class poets and writers getting the chance to have their voices heard?

There are not enough working class writers getting their chance, but I think things are definitely improving, at least in the independent presses. Novelists such as Kit de Waal, Adele Stripe, Kerry Hudson, and Natasha Carthew are relatively new (and Alex Wheatle for the past 20 years), are writing some great work that is not patronising or demonising. In poetry, the publisher of my book, Smokestack Books has been the mainstay of working class poetry for a couple of decades. But new presses are emerging; presses like Culture Matters, Burning Eye, and the most recent Verve Poetry Press.

What, in your opinion, are the essential elements for a positive poetry gig experience?

I think you’ve got that covered already; drinks and food on hand, an inclusive open mic, split headliners, and a good venue. Fire & Dust felt very democratic.

What inspired you to set up Proletarian Poetry, and how’s it all going?

Proletarian Poetry was my entry point to poetry. I asked myself what was the best way into the poetry world, and with any new process, it’s all about getting to know people. In that regard, I was very fortunate being blighted by class, as I didn’t really know if there was a gap in the poetry market so to speak, and asking poets if I can feature their poem with an introduction has yielded a 99% a positive response (and of the 1% it was just that their poems were already promised elsewhere).

As editor of Proletarian Poetry, what are the key elements you look for when deciding whether a submitted poem is “good” or still in need of work?

That is a good question, but one that is easier to answer – I choose poems that I like, but also ones that I can riff off with my commentary. I don’t have an open submissions process, as I would not be able to write all the features. So I simply look out for poems that are relevant to the site, and as I say, that I can write about.

Would you say the process of reading and critiquing submissions has had any positive impact on your own writing practice?

As I say, I don’t really critique them as they are usually the finished product already. However, I nearly always type them out myself; I think this is a good way of doing a close reading, and unless it is the Waste Land, a very practical thing to do. Then writing the feature, helps my own poetry, as it sets the poems in a context so I see extra depth to the poem that I may not have caught on just reading – although I only do this at the editing stage, as doing it at the beginning would be too constraining and probably would lead to a poor poem.

Do you read much poetry for pleasure, or is it too much like work? Have any new collections/performers recently made an impression on you?

I do read for pleasure, but also for ‘work’. I think it important as a writer to separate the two – but it is difficult. It is much easier to read another genre of writing for pleasure than poetry, if you are solely a poet. At the same time, I would recommend reading widely (original, right?), but don’t always have a pencil in hand.

I am very impressed with US poetry at the moment. Poets such as Terrance Hayes, Eve Ewing, Erika L Sanchez, Jacob Saenz, Martin Espada, Fred Voss, Kyle Dargan, and Danez Smith. They really give you a feel of the political zeitgeist going on in the States at the moment. Mainstream UK poetry tends not to reflect that so much; it still seems to be stuck in some 19th century Romantic style of lyric poetry. But poets in the UK who are bucking this trend include Fran Lock (brilliant!), Rishi Dastidar, Jane Commane, Martin Hayes, Nafeesa Hamid, Casey Bailey, Julia Webb, Nadia Drews, Tim Wells, Chip Hamer, Melissa Lee Houghton, Ann Robinson, Bobby Parker, Jane Burn, Mike Jenkins, and Malika Booker.

What projects/performances have you got coming up next?

I am hosting a Proletarian Poetry showcase at the Verve Poetry Festival in February which I am excited about. The poets on show are: Amir Darwish, Rishi Dastidar, Anna Robinson, Nadia Drews, and Julia Webb.

I am currently 8K words in of a verse novel (six characters, each with a six line stanza per page) set in Brixton in the late 70s/early 80s, about class and race. It is my most nerve wracking writing experience to date.

Share any other links/social media you’d like to plug here:

Proletarian Poetry Twitter: @ProletarianPoet

Where can people get hold of your books?

Precarious from: Smokestack Books

Precarious from: Hive

The Combination: a poetic coupling of the Communist Manifesto from: Culture Matters