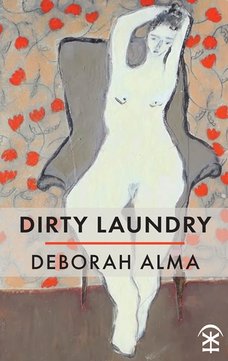

REVIEW: DEBORAH ALMA’S ‘DIRTY LAUNDRY’

DIRTY LAUNDRY BY DEBORAH ALMA

Nine Arches Press

ISBN: 978-1911027416

£9.99/80 pages

Reviewed by: Stella Backhouse

For me, the turning point of Deborah Alma’s debut collection Dirty Laundry comes near the end. Until that point, Alma’s poems brim with people: friends, family and – most notably – lovers. With the lovers, it usually ends badly. I wonder why she keeps putting herself through it. In ‘No-one but the AA’, the answer rears up, stark and shocking – it’s because the alternative is “a car crash in a country lane/ in ice…and no-one but the AA to call”.

For me, the turning point of Deborah Alma’s debut collection Dirty Laundry comes near the end. Until that point, Alma’s poems brim with people: friends, family and – most notably – lovers. With the lovers, it usually ends badly. I wonder why she keeps putting herself through it. In ‘No-one but the AA’, the answer rears up, stark and shocking – it’s because the alternative is “a car crash in a country lane/ in ice…and no-one but the AA to call”.

As its name implies, Dirty Laundry is about making public what some people would prefer should remain under wraps. Those people are mostly men. What they would prefer to keep hidden is their behaviour towards women, and its effects. In ‘Still life’, “Digby’s approach is to sweep things under the carpet…the cunts, the bastards, the bitches…that he threw/ not imagining the mess”. Quietly ominous ‘Small Town’ offers disturbing glimpses of a life stunted by “something to do/ with what you did to me”. Even men whose dedication to the arts might raise hopes of sensitivity are exposed as reflexively ungrateful, oblivious to the fact that space for writing their “great novel” exists only because a woman downstairs “puts another load on”.

Alma’s revenge, lusty and full-bodied, is to drag the whole lot – kicking and screaming if necessary – out for an airing. To the patriarchy that has shamed and silenced women for centuries with claims that the reality of their bodies is too disgusting to be witnessed, her response is in-your-face and unambiguous. A miscarriage is heralded by “the dragging down blood”; cockle wives “take care to lift their skirts,/ squat to piss”; the poet laments her aging thighs with by rubbing them with butter and “looking for signs”. Both in title and in themes, Dirty Laundry bears the same mussy imprint as Tracey Emin’s My Bed.

Similarly red in tooth and claw is the farming community that is the backdrop to most of Alma’s poems. Expired chickens, dead moles drying on a fence and cattle to slaughter are dealt with matter-of-factly; but the truth about where our food comes from is another aspect of life most of us turn a blind eye to. In ‘Naive City Eyes’, a hippy-ish hitch hiker is disgusted by Alma’s boyfriend, fresh from the abattoir, splashed with blood and literally red-in-tooth.

Binding everything together is Alma’s deep affinity with the countryside where she lives, creating a unified internal and external landscape that is earthy, ancient and mediated only by the lived experience of the female body. Too-needy men are heaved out of bed like cuckoos from a nest; thighs are places to cradle injured birds; sex is a place to “sing/ strong as blackbirds”.

By the end of the book, Alma has decided to stop basing her identity on approval from men. In ‘The Magic Spell’ she says, “I live alone. Keep chickens, ducks, no lovers. They are there for the spell and not for me. I do not believe in them”. But despite her aging body, in her womanhood she is pure and unashamed: “I am each of the processes of laundry/ but most, the unfolding in winter/ of sheets – a sudden punch/ of trapped summer on white linen – heat”. Bloodied but unbowed, she is living and speaking on her own terms. She has not surrendered.