REVIEW: ‘THE BOOK OF COVENTRY’

By Stella Backhouse

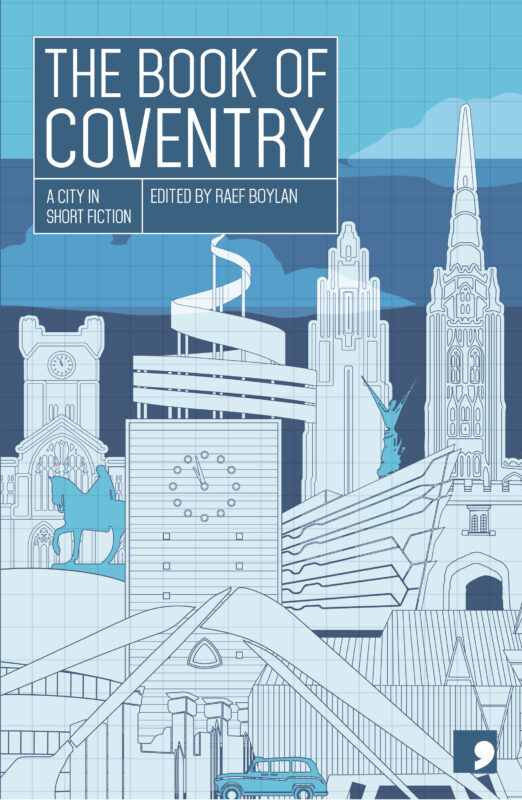

In his introduction to Comma Press’s Book of Coventry: A City in Short Fiction, editor Raef Boylan says that what those behind the project were seeking from the eleven short stories showcased here was “narratives that couldn’t have happened in any other place”. Especially with a city as overlooked as Coventry, the urge to identify it – to itself as much as to anyone else – is understandably strong. But when any USP Coventry does have is often said to be its diversity, could the endeavour to capture a shared or recognisable essence perhaps be just a fool’s errand?

In his introduction to Comma Press’s Book of Coventry: A City in Short Fiction, editor Raef Boylan says that what those behind the project were seeking from the eleven short stories showcased here was “narratives that couldn’t have happened in any other place”. Especially with a city as overlooked as Coventry, the urge to identify it – to itself as much as to anyone else – is understandably strong. But when any USP Coventry does have is often said to be its diversity, could the endeavour to capture a shared or recognisable essence perhaps be just a fool’s errand?

One of the strong points of Book of Coventry is the assurance with which it acknowledges this paradox. Nirmal Puwar’s ‘Ten Windows’, for example, wrestles the difficulties of welding a plethora of conflicting visions and stories into a single ‘house’. Meanwhile, ‘The Worst Thing’ by Andrew Davies (one of a couple of bigger names included in the book) confronts the ‘town and gown’ dilemmas of a middle-class writer whose raw material is the working-class city that surrounds him. Marital infidelity, it turns out, is common to every class. In Mez Packer’s ‘Daughter of the Family’, the promise of new life and the age-old solidarity of women sanctifies a mixed-race relationship.

A measure of the extent to which the book succeeds in getting under Coventry’s skin is that two of its strongest themes will both be very familiar to anyone who knows the city. The first is resilience. In both Puwar and Packer’s contributions and in Cathy Galvin’s more equivocal ‘An Education’, this is expressed in terms of standing up to violent racism, asserting your right to belong in Cov and to build a proudly multi-cultural city. Graham Joyce’s ‘The Coventry Boy’ recalls the heroic efforts of those who tried to save the city on the night of 14th November 1940. Holly Watson’s tragi-comic monologue ‘Lucky Lyn’, homes in on a woman who fills her otherwise empty life with a passion for consumerist ‘no purchase necessary’ competitions.

The other theme that emerges repeatedly is the hidden or underground nature of Coventry’s cultural life. In Tanya Pengelly’s ‘Carriages at Three’ this is quite literally the case as a young archivist, new to the city, trawls through miles of documents kept in store underground before finding and cataloguing the girlhood library of the writer who would become George Eliot. It’s also present in the supernatural elements of ‘The Coventry Boy’ and of Nuzo Onoh’s ‘Graffiti’, in which Lady Godiva returns to catapult the life of a previously ordinary young woman into the realms of the fantastic. Both imply that another Coventry is waiting if only we can find it. In Nick Walker’s ‘Sightseeing’, the only story to take us beyond the boundaries of Cov, a few hours away brings deeper understanding of the city’s meaning.

As much as the story-telling, the fun of a collection like this often lies in the chance to re-imagine familiar locations in unexpected ways – I particularly enjoyed seeing what I took to be Cheylesmore’s Kenilworth Court flats complex in its full 1960s glamour as a “flash” gangster HQ in ‘The Worst Thing’. More broadly, knowledge of the city’s geography invites readers to bring their own memories into play so that the book itself becomes a tool for creating community. Weaving memories of childhood adventures in the spinneys bordering Kenilworth Road with present-day concerns about her increasingly-demented ‘Mother’, Andrea Mbarushimana’s ‘Spun’, not only reminds us that far from a concrete jungle, Coventry contains precious remnants of ancient woodland within its boundaries, but also situates the city within the wider community of nature and struggling ecosystems.

If I had a criticism of Book of Coventry, it would be that too many of the stories are about its past. In some cases, such as David Court’s ‘Four Minute Warning’, it’s an under-explored episode with obvious contemporary relevance, but reference points such as Lady Godiva and the Coventry Blitz have perhaps become a little too obvious. I would have welcomed a bit more present-day reality and a bit of speculation on the future. That said, this collection cannot fail to warm the heart of anyone who loves Coventry; it would make the perfect Christmas gift.

The Book of Coventry (and other titles from the ‘reading the city’ anthology series) is available online direct from publisher Comma Press, as well as other bookshops and retailers.