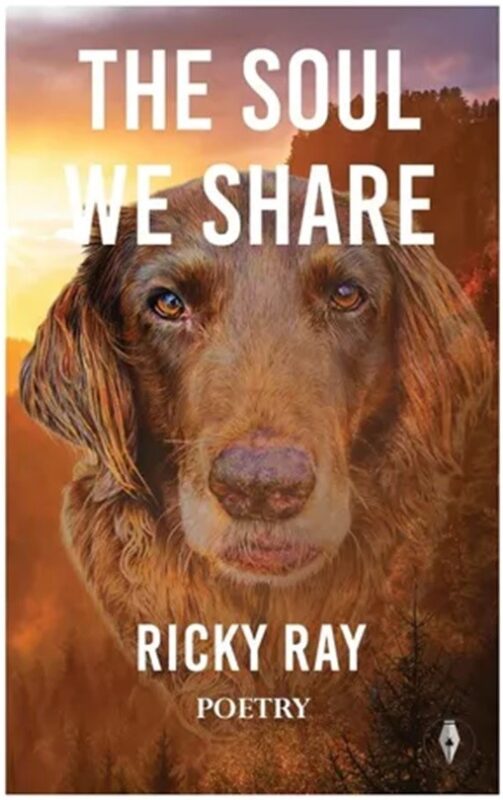

Review: Ricky Ray, The Soul We Share

(Fly on the Wall Press, 2024)

By Meg Freer

The Soul We Share, a new collection by American poet, essayist, and self-described mystic Ricky Ray, takes as its impetus his shared life with his beloved dog Addie, who taught him patience, tolerance, and close observation of the environment, but it is so much more than a book for those who have also shared their lives with a beloved animal. This book is nothing less than a poetic manifesto challenging us to do better, notice better, live better, and love better, for the sake of our mother Earth who sustains us. Ray is a living poet, not only in the usual sense, but also in the sense that he lets the reader know that it’s possible to be living poetry all the time. Even the endnotes to this book are poetry themselves and, in effect, become extensions of the poems themselves.

The Soul We Share, a new collection by American poet, essayist, and self-described mystic Ricky Ray, takes as its impetus his shared life with his beloved dog Addie, who taught him patience, tolerance, and close observation of the environment, but it is so much more than a book for those who have also shared their lives with a beloved animal. This book is nothing less than a poetic manifesto challenging us to do better, notice better, live better, and love better, for the sake of our mother Earth who sustains us. Ray is a living poet, not only in the usual sense, but also in the sense that he lets the reader know that it’s possible to be living poetry all the time. Even the endnotes to this book are poetry themselves and, in effect, become extensions of the poems themselves.

The book takes the form of a musical work, with five movements cradled by a prelude and a coda, and a prose interlude halfway through. The Interlude, titled ‘Identity Earth: A Brief Biography of Our Planetary Self’, is a lyric lecture, a holistic examination of life. There is no Big Bang here, but music: “a single stroke commencing the grand symphony we call existence” (p. 67). Musical references appear throughout the book, such as this from the poem ‘Resolution’: “Body, I hear you singing to yourself” (p. 28). There are other recurring motives: ‘Aches’ (brief haiku-like verses) and a set of ‘Walk with Addie’ poems. The walk poems begin the first two and last two movements and create an arch-like structure to lead us through the collection.

One of the first movement’s themes is how we enter into the mind of Earth (or of a dog) without speaking, as well as into the mind of the one who lives with physical pain. The imagery of pain is sharp, as in the last poem of ‘Aches’, Quartet #1: “I want a poem so close to hurt / it bruises my lips on the way out” (p. 22).

Another theme is how everything around us, even inanimate stone, whispers of past lives, so that all becomes one. The introductory four-part poem ‘The What of Us’ ends like this: “How beautiful that who / was always a brief glimpse / into what” (p. 13). The poem ‘Petty Theft’ offers a comforting image: “To be at home in the Earth’s pocket, where I’ve always been” (p. 55). The last poem of the second movement, ‘So Long as There Is Light, There Is Song’, tells us: “There’s another one here. The one who lives us. / In whose breath we are held. In whose voice we are sung” (p. 63). And from ‘The Soul We Share Survives Us’, Ray wonders: “how to let the bodies we have / (atom, cell, life, friendship, dog) / surrender to the bodies we belong to / (wind, water, love, woods, Earth)” (p. 136).

A life as a poem. But there are also subtle warnings about the consequences of our actions against our earthly home and ourselves. Light as a theme often appears out of these shadows to lead us on from section to section. From ‘How to Go On’: “It’s easy: / you open your mouth, / you take in little sips of light” (p. 38). Light in the form of recognizing joy and love despite assaults on the mind and heart. The poet finds love in sips of water, in the soil as soul, in quiet solitude. In the prose poem ‘Love Is a Drug Passed Shyly Between Fathers and Sons’, we discover: “there’s love in quiet, in keeping apart” (p. 61).

The entire third movement is a fourteen-part, reflective, narrative poem, ‘And Then, Very Gently’, prompted by a threatening storm. It asks questions of the reader: How do we figure out what “do better” is? How do we heal the Earth? How do we notice our “eco-vision” and see what’s going on around us? How do we get others to notice? How do we effect “a troubling of consciousness that / … someone needs” (VII, p. 83)? Perhaps we do and can by means of this kind of poetry, which manages to be both delicate and forceful in its language and intentions.

The fourth movement begins with ‘Walk with Addie: The Drska Forest in Danbury’, when “the light / was honey” and “Earth’s children leapt into our faces and said notice me” (p. 93) and then moves on to poems about the body’s ailments and frailties, the body as part of the Earth, the Earth as ourselves, the Earth holding us the way she holds Ray himself and his dog Addie in the hole they dug together.

This over-arching theme of devotion continues in the fifth and last section of poems. After beginning with broken bodies, the poet turns to love lyrics for his wife, the child he wishes he had, and the dogs he holds in his heart. Keep a hankie handy for the Coda poem, ‘The Last Walk’, a moving tribute to Ray’s dog Addie. He learned from her how “to live as ecosystems inhabiting creatures as much as creatures inhabiting lands” (p. 157) – what dogs probably just do naturally. This recurring theme becomes especially clear in the poem ‘The Daughter You Almost Had’: “when the soul comes limping, / you think of her, / and you choose the lightswitch labeled help” (p. 35).

May we all choose that lightswitch labeled help as we go through our own days, and may we also, as the poet does in ‘The Tribe of Two Legs and Spit’: “Let be, don’t harm, / offer an ear, a minute’s help” (p. 130). There are many references in this collection to autumn, Ray’s favorite season, so this season would be a nice time to buy this beautifully produced book from Fly on the Wall Press (UK) for yourself or for a friend.

September 20, 2024

© Meg Freer

The Soul We Share can be purchased online direct from publisher Fly on the Wall Press, as well as other bookshops and retailers.

Our guest reviewer Meg Freer lives in Ontario, Canada, where she is a writer, editor, and piano teacher. Her short prose, poems, and photos have appeared in many journals and she has published three poetry chapbooks. She is co-poetry editor for The Sunlight Press and a member of the Ontario Poetry Society and the League of Canadian Poets. Find Meg’s published work on her Facebook page or her Substack blog.