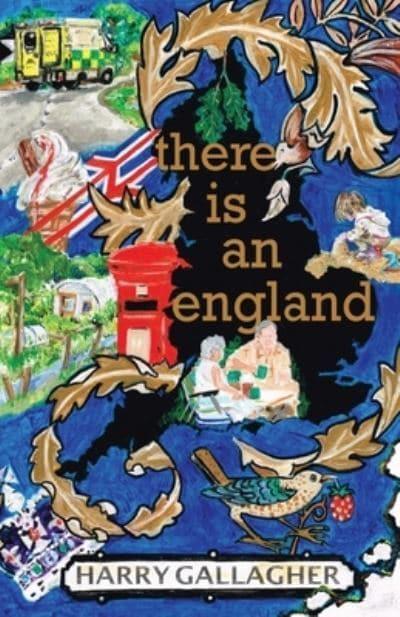

REVIEW: HARRY GALLAGHER’S ‘THERE IS AN ENGLAND’

By Stella Backhouse

These are the facts: in the 2016 EU referendum, England’s North East registered the third highest leave vote by region; nationally, the older you were, the more likely you were to vote leave; and more men than women voted leave. So, if you’re Harry Gallagher – a poet so loved in his native North East that his earlier collection, Northern Lights, was for a time the most borrowed book in Newcastle-Upon-Tyne Public Library, a poet whose choice of references suggests that his target audience sits squarely in the fifty-plus age bracket and a poet who appears particularly keen to reach out to men – I can only say that publishing a collection that argues that ‘leave’ was the wrong decision could look like a spectacular act of self-sabotage.

In fact, Gallagher’s new collection, there is an england, squares this circle by presenting Brexit as an unwitting act of class betrayal. England’s white working class, he argues, is a fundamentally decent social group whose historically fair-minded instincts have been hijacked and subverted by politicians and by media both traditional and online. Supporting this analysis are historical-perspective poems about Arthur Wharton, the man usually credited with being the world’s first black professional footballer, who began his career at Darlington FC; and the affinity between British coalminers and Paul Robeson, the McCarthy-targeted African-American activist and performer.

As for solutions, Gallagher seems to advocate a return to the past – what he sees as the real past, described in his self-penned introduction as class pride in “the things that made the nation great – a sense of fair-play, decency and tolerance”. At times the results – at least for me – stray a little too close to John Major’s cosily-nostalgic visions of “long shadows on county [cricket] grounds, warm beer, invincible green suburbs, dog lovers, and – as George Orwell said – old maids bicycling to Holy Communion through the morning mist”. The title poem, for example, celebrates “ginnels between houses/whose doors bear a welcome,/kettles ever bubbling,/sofas ever dented from/shared laughter at daftness” and “bus drivers dispensing/directions like boiled sweets/to confused old wayfarers”.

Elsewhere though, Gallagher is more hard-hitting. ‘Island’ reads almost like it’s been spat onto the page: “How can you say/we are bigger and better/when we are/a pinprick/of blood on a map?”. ‘Song of the Six Million’ anticipates the recent Gary Lineker/Suella Braverman stand-off by pointing out that “It didn’t begin with uniform wearers…It started on the streets, in the shops/and bars, with late night whispers/and jokes about the Jews and who’s/to blame for all the ills of the day”. Gallagher’s message however, is ultimately one of hope and decency winning through: ‘You Do Not Speak for Me’ for example contrasts “Your tone is shrill,/a study in antipathy” with “my England./Its voice is not scabrous,/it is soft”.

Included as subsidiary themes are climate change and concerns about the state of the world Gallagher and his peers are handing on to their grandchildren. And amidst hints that his relationship with his own father was problematic, he is also interested in masculinity and, in particular, in men’s attitude to poetry. In this context, ‘Meeting Male Audience Members After Poetry Readings’ is perhaps the book’s most endearing poem; its portrait of men who “afterwards, stealthy as/a nightshift worker,/with everyone else/hidden safely from sight…cross the shopfloor…eyes puddling, they shrug/and tell me tersely/(just between me and them like)/smashing that, mate” is so vividly drawn and rings so true that it can only be the result of real experience, repeated many times.

The extent to which this collection appeals to you may depend on the extent to which you share its assessment of Britain’s past and present. There were many aspects of it that I found clumsy: I see little glory, for instance, in belonging to “the nation who wrote/the world’s history books” if that distinction was only achieved by the deliberate suppression of other narratives; I disagree that female care workers are “powered by thanks/and a job well done” – no, they need fair pay like everyone else. But you’ve got to admire a poet who who is brave enough to use his poetry as a vehicle for speaking the truth as he sees it – even when that truth seems unlikely to make him popular.

there is an england is available to purchase online, direct from publisher Stairwell Books, as well as other bookshops and retailers.